The Invisible Hand of Storytelling: Valerio Vincenzo on Editing With Heart and Logic

Valerio Vincenzo is the Director of Photography at GEO magazine in France. An Italian-French photographer, he is best known for his project Borderline, les frontières de la paix, which documents 20,000 km of borders without barriers in Europe. Formerly a business strategy consultant, Vincenzo exhibited widely and was published in major outlets including Le Monde, CNN, and Financial Times. His work focuses on borders, identity, and the evolving human relationship with space.

In addition to his editorial and artistic work, Vincenzo is active in educational outreach through the association Borderline, les frontières de la paix, which promotes peace education and European integration. He continues to explore new artistic directions, blending documentary photography with conceptual and digital investigations.

©Mehrak

FROM BOARDROOM STRATEGY TO SHAPING STORYTELLING

HM: Valerio, it’s not every day we meet a Director of Photography who only discovered photography at 25. Can you tell us how it all began?

VV: Yes, quite late compared to most. I studied Business Administration and started out as a strategy consultant. It was a job I truly enjoyed, intellectually stimulating and demanding—but it took over my life. I had no time for anything else. That’s when photography entered the picture. I began carrying a camera everywhere, even to business meetings. Between the ages of 25 and 30, I started experimenting with black-and-white photography. I wasn’t particularly good, but I was deeply drawn to the darkroom process—the quiet, deliberate time spent working with an image. That intimacy with the photograph, the space to reflect and improve, really captivated me.

HM: And then came the surprise…..?

VV: (laughs) Yes, for my 30th birthday, a group of close friends—good friends!—pooled together and gifted me a Leica M5. A purely manual camera. They said, “Why don’t you really give this a try?” So I did. I left my job, moved to Paris, and told myself I’d give it six months to explore photography seriously.

HM: That’s a big leap, from boardrooms to darkrooms in Paris?

VV: It was. I enrolled in a short, four-month course on photojournalism. Interestingly, it wasn’t about technique. They weren’t teaching us how to use a camera. It was very pragmatic—how to approach magazines, how to build a portfolio, what to pitch and what to avoid. It was the professional grounding I needed.

The images in this article are an example of double spreads in the print version of GEO France magazine, where Valerio acts as Director of Photography. Here is the opening double spread of a portfolio by George Steinmetz (USA) published to illustrate an interview on agricultural geopolitics. The image shows the world’s biggest sheep market in Australia.

HM: You began from scratch. No network. How did you get your foot in the door?

VV: I knew I couldn’t go straight to publications like Le Monde. So I went to the National Library and made a list of obscure magazine photo editors—publications so small you wouldn’t find them on kiosks. I sent out nearly 100 pitches. Maybe one or two wrote back, but that was enough. I started doing basic portrait assignments. The layouts were awful (laughs), but it gave me room to learn and make mistakes. No pressure.

HM: And in parallel, you began your personal projects?

VV: Exactly. One of the first came from a place of personal confusion and melancholy. It was winter, I felt a bit lost. So I got a pass that allowed unlimited access to movie theaters. At first, I photographed the screen—long exposures—but soon I became fascinated by the audience. I started photographing viewers as they sat, absorbed, unaware. I was interested in this concept of collective solitude—you’re alone with your emotions, but also part of something larger. That duality intrigued me.

HM: You often showed personal work during meetings. Why?

VV: Editors were often intrigued by those projects. Even if they didn’t assign me something directly related, they seemed to appreciate the thinking and vision. Sometimes they gave me unrelated jobs—landscapes, portraits—but I believe, in a way, they were helping me finance my personal work.

HM: Can you talk about your long-term project on borders?

VV: That became my central work as a documentary photographer. I spent 13 years photographing 20,000 kilometers of borders—between countries at peace. The focus was never on the physical walls or barriers, but on everything but the separation. I wanted to show life, movement, subtle tensions, and invisible lines. It was a way of exploring identity, proximity, and the artificiality of borders.

HM: Then in 2022, a shift—you declared you were no longer a documentary photographer?

VV: Yes, I transitioned into a more conceptual, artistic practice. I became fascinated by our relationship with the camera—especially digital cameras. Does the tool itself shape the way we perceive and engage with the world? That’s the question I wanted to pursue. So I began a new series of works on that theme. While on an artist residency in the suburbs of Paris, I got a call from GEO France.

HM: That was a turning point. What did they offer?

VV: They offered me the role of Director of Photography. I was hesitant at first. I told them I was an artist now—not interested in searching agency archives for photos. They said, “That’s not the job.” They sent over the job description. It had ten bullet points. And for the first time in my life, I liked all of them. Every part of it seemed meaningful and exciting. So I said, “Let’s try it.” And here I am, three years later, still loving it.

Example of the layout of the portfolio by George Steinmetz published by GEO France.

HM: How has being a photographer shaped how you approach this role?

VV: Immensely. I had no idea how a magazine actually works from the inside. As a photographer, I often found editorial decisions frustrating or irrational. Now I understand the constraints—deadlines, narrative structures, page layouts. But I also see how disconnected some editors are from field realities. So I try to be the bridge. I explain the photographer’s challenges to the editorial team, and vice versa. I’ve never stopped being a photographer, and I think that’s appreciated.

HM: And today?

VV: Since early 2025, I’ve shifted to a four-day workweek at GEO. Fridays are for my art practice. I’m continuing my research on how technology changes our gaze, but at a slower pace. Balancing both worlds—editorial leadership and artistic exploration—is a challenge, but it keeps me connected to what really matters.

A PHOTOGRAPHER IN THE EDITOR’S CHAIR

HM: Valerio, you mentioned that a major part of your role at GEO is to act as a bridge between photographers in the field and editors in the newsroom. Can you tell us more about that dynamic?

VV: Absolutely. One thing I quickly realized after stepping into this role is that many editors—though deeply talented and passionate—often lack firsthand experience in the field. They haven't had to deal with capricious weather, logistic constraints or reluctant subjects. So their expectations or decisions can sometimes feel disconnected from the real conditions photographers face. My role is to connect those two worlds: the one where stories are imagined and assigned, and the one where they're actually produced—with all the messiness and unpredictability that entails.

HM: So you’re functioning as both interpreter and advocate?

VV: Exactly. I try to explain to the editors the constraints and nuances that photographers are dealing with—logistics, timing, safety, weather, access. And I also try to help photographers understand the editorial logic: why certain images are prioritized, why the layout must follow a particular narrative arc, or why captions are non-negotiable in a journalistic publication like GEO. I believe this dual understanding is what makes my role unique. I still think of myself as a photographer first. That perspective grounds me, and I believe it's one of the reasons I’ve been able to gain trust on both sides.

Opening image of the story Valerio assigned to the Indian photographer Arko Datto to document the incredible journey of voting machines in India. For a month and a half, millions of civil servants brought electronic ballot boxes to the most remote corners of India for the 2024 general elections. Their challenge: to enable each of the 968 million voters to take part in the ballot close to home.

HM: Is there a tension between being a photographer and being Director of Photography?

VV: There is, definitely. When I accepted the role, I made a conscious decision: I removed all of my work from the agency that represented me. Not because I no longer believed in it, but because I felt that I couldn’t continue contributing as a photojournalist while also curating and commissioning others’ work. There’s a line, ethically and practically. That doesn’t mean I’ve stopped photographing—on the contrary, I continue as a visual artist—but my personal work now lives in a different space. I no longer take photojournalistic assignments. I want to be fully committed in my role as Director of Photography, while never forgetting what it means to work as a photographer.

HM: Do you have a vision for GEO's visual identity? How do you define what makes a photograph or story right for the magazine?

VV: Yes, and that’s been an evolving journey. When I started, I’d come back from festivals excited by work that was visually striking—artists with bold aesthetics and conceptual depth. But those stories were often turned down here. Why? Because at GEO, the foundation is always the story. No matter how beautiful the images are, they must be anchored in a clear, compelling, journalistic narrative. And that makes sense. Sometimes, we publish stories where the text is stronger than the images, because the topic is urgent or meaningful. Ideally, of course, we want both—strong visuals and a strong story—but it’s not always possible.

HM: That’s a tricky balance. How do captions play into that?

VV: Captions are essential at GEO. Every image must have one. That’s a fundamental rule here, and it’s one of the biggest differences between journalistic and fine art publishing. In a gallery setting or a photobook, you might show a series of images without any text—letting the viewer interpret freely. But in journalism, we are dealing with facts. Captions provide context, nuance, and grounding. They help ensure that readers understand not just what they’re seeing, but why they’re seeing it. That said, I do sympathize with the idea that captions can sometimes limit imagination.

HM: You’ve mentioned that. Can you say more?

VV: Sure. There’s this photographer I admire—Martin Kollár—and he once said that he doesn’t want his images captioned at all. He wants viewers to bring their own interpretations, unfiltered. And I understand that. There’s beauty in ambiguity, in leaving space for the viewer’s imagination. But again, that works best in certain contexts—fine art, experimental publishing—not in a magazine like GEO, where credibility and clarity are essential. Still, I think there should be space in our field for both approaches.

HM: That brings us to a bigger question: what makes a photographic story truly stand out to you?

VV: My criteria have changed over time. Three years ago, I was more visually driven. Now, after reviewing thousands of submissions, my first reaction is shaped by novelty. Has this story been told before? Is the angle fresh? Is it set in a place or community we rarely hear about? The second layer is execution: Is the visual language coherent? Are the frames strong? Is there a clear rhythm to the images, a sense of narrative momentum?

Voting is about to begin and voters are returning to their island in the Bengal delta, devastated six days earlier by a cyclone (photo: Arko Datto)

HM: So originality and craft?

VV: Yes, but also emotional connection. A story might not be groundbreaking, but if the photographer has managed to establish real intimacy with their subject, or captured something subtle and truthful, that carries weight. And of course, there are practical considerations too. For GEO, we need stories with journalistic backbone—access to sources, verifiable facts, and imagery that helps illustrate the world as it is, not as we wish it were. The caption must carry weight. That’s the DNA of the magazine.

HM: What remains with you after reading a story? Is it the caption, the photograph, or something else?

VV: That’s a fascinating question. I recently went through some old portfolios I had saved—photographers I admired, projects I loved—and I noticed something: I remembered the photos clearly, but not the captions. Not even the precise storylines. My memory had morphed the stories over time. But the images? They stayed vivid. That says something about the power of visual memory. Of course, when it comes to politically or socially sensitive topics, captions are crucial to avoid misinterpretation. But there’s room for more open-ended, poetic storytelling too.

HM: You seem to be navigating that line—between clarity and imagination, aesthetics and ethics—with a lot of thoughtfulness.

VV: I try. It’s not about absolutes. It’s about recognizing that storytelling through photography is both an art and a craft, both an act of documentation and interpretation. And as long as we respect the responsibility that comes with it—especially in journalism—I think there’s space for many voices, many approaches.

THE AESTHETICS, LOGIC, AND LIMITS OF PHOTOJOURNALISM

HM: Valerio, when reviewing submissions or assignments for GEO, what criteria do you apply in determining if a story works for the magazine?

VV: The first thing I ask myself is: Am I just looking at a trend? For instance, if everything is desaturated or follows a certain visual fashion, I get suspicious. I ask: Is this aesthetic helping to tell the story, or is it just a style choice disconnected from reality? At GEO, aesthetics must serve the narrative. They need to support the truth of what’s being shown.

The second thing I look for is visual diversity. Our main features run between 12 and 16 pages, sometimes more. That demands a variety of visual situations: interior and exterior shots, portraits, landscapes, close-ups, wide scenes, moments of action, moments of stillness—ideally across different times of day. We’re not looking for ten versions of the same scene. We need a rich visual grammar that supports multiple layouts and entry points into the story.

HM: So it’s not just about “great images”—it’s about the structure they create together?

VV: Exactly. A good photo isn’t enough. We build multiple versions of the layout for every feature—sometimes printing different combinations and pinning them on the wall. We test how ten strong photos work together visually, thematically, rhythmically. If a story only offers three or four distinct visual situations, it simply won’t hold a full feature. That’s a deal-breaker.

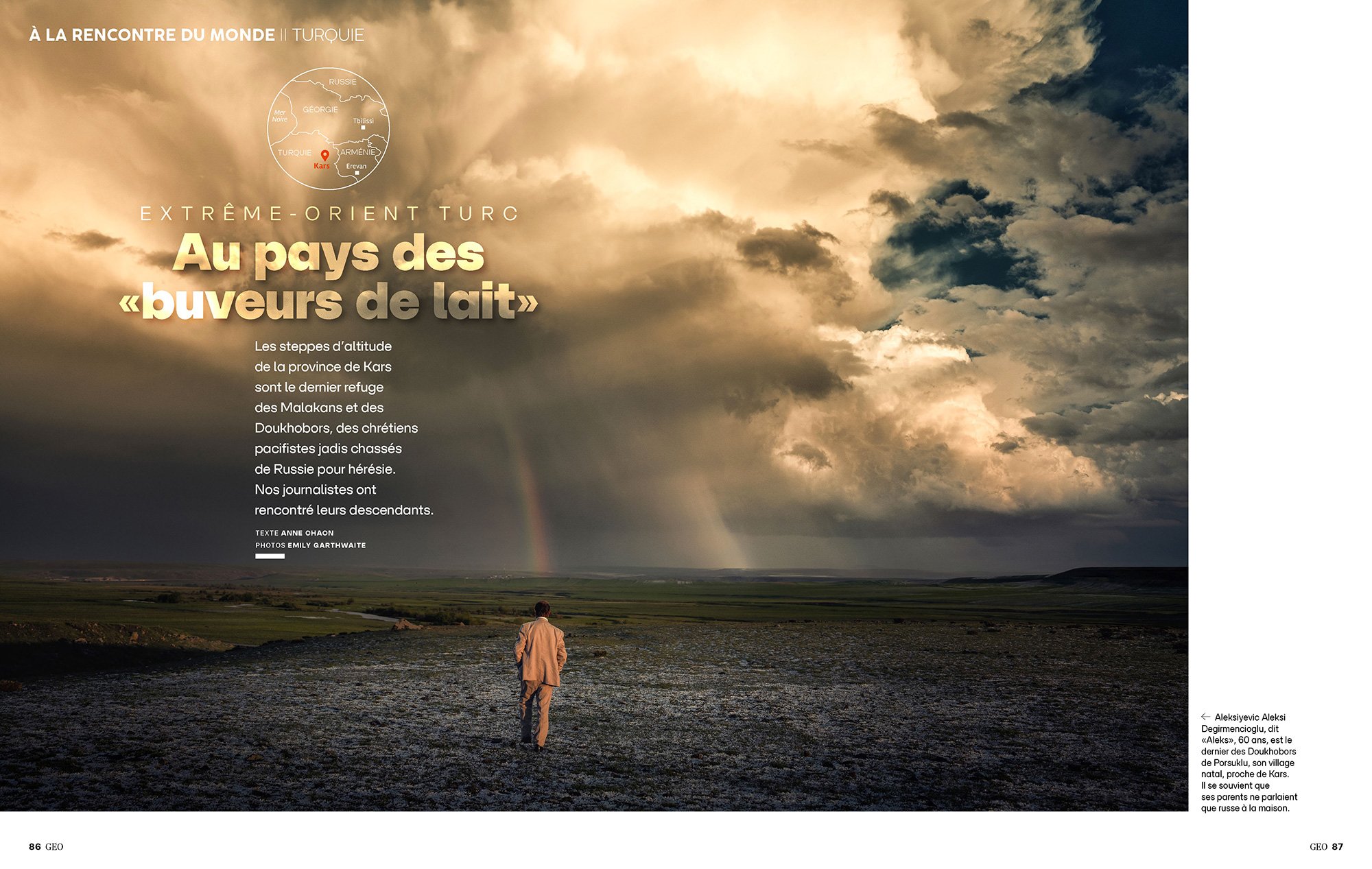

Story commissioned by Valerio to the photographer Emily Garthwaite and published in the May 2025 issue of GEO France. Emily traveled to Turkey to meet the descendants of the Malakans and Doukhobors, Christian pacifists once expelled from Russia for heresy who found refuge on the high steppes of Turkmenistan's Kars province.

HM: Does the format of GEO—as a print-first magazine—affect the way you work with photographers?

VV: Hugely. We’re still a paper publication. So double-page spreads are a big part of our visual identity. That means the composition of each photo must consider the physical fold of the magazine—action at the center can be lost. We think in terms of page flow and spatial coherence. We shoot for print first. Web comes after.

HM: When you assign a photographer, what do you look for?

VV: It depends on the story. For something logistically complex—say, a story on coca plantations in Colombia—we need someone with deep experience in the field, someone who already has contacts, understands the risks, and can move safely. That sometimes matters more than artistic skill.

Other times, I need a photographer who is versatile: someone who can shoot portraits and landscapes, maybe even drone photography, and adapt to a range of visual needs. Sometimes, I need the opposite—a strong personal visual style that aligns perfectly with the tone of the story. I try to match the photographer’s strengths with the nature of the project.

HM: Do you ever build assignments around existing work?

VV: Yes, often. Because we can’t afford to send someone for a month and risk not publishing the work. If a photographer already has material that fits part of the narrative—say, landscape images from the region—we might assign an extra week for them to shoot people, action, or specific locations. That way we minimize risk. It's a hybrid approach that works well under budget constraints.

HM: How often can you collaborate with the same photographer?

VV: That’s one of the frustrations of the job. We’re a monthly magazine. That limits how many stories we can publish in a year. So even with photographers I admire, I might only commission them once a year. It’s also why I try to assign local photographers whenever possible. If we’re covering Peru, I’ll look for someone based there. It’s more sustainable, and it allows us to work over time—spread across seasons. Sometimes a one-week assignment becomes a nine-month collaboration, simply because the photographer can return, observe changes, and go deeper.

This shot by Emily Garthwaite, which was published as a double spread in GEO France, captures the vibrant melting-pot atmosphere of the local culture.

HM: How much creative freedom do you give a photographer on assignment?

VV: That’s a complex question. The honest answer is: not much, at least at the start. Before any assignment, we provide a detailed brief. It includes a number of specific visual situations we expect—locations, actions, people, types of shots. The photographer’s job is to deliver those first. Only after that do they have space to explore freely.

It’s a structure that can feel limiting. But it’s necessary. We need to ensure the material is usable for our format. That said, we absolutely welcome surprises—unexpected discoveries, alternate perspectives, creative proposals. Some of our best published images weren’t part of the original plan. But they only made it in because the core brief was fulfilled first.

HM: For photographers who value creative freedom, is working for GEO worth it?

VV: I think so, yes—but they need to understand what they’re signing up for. There are constraints, yes. But assignments are incredibly nourishing. I speak from experience—many of my own long-term projects were born during assignments. You go for one reason, but then something else catches your eye, and it becomes something more. Even an assignment you’re not excited about can spark a new idea, or lead you into terrain you never imagined.

HM: That’s a beautiful way to look at it. Can you share any specific examples?

VV: Sure. I was sent by a local magazine to photograph a theme park on the outskirts of Paris. Although it was a small assignment requiring only one photo, after taking a few shots for the magazine, I realized I was more intrigued by the contrast between the theme park – an artificial place of amusement – and its surroundings, which represented the real world. This sparked the beginning of a long-term personal project that led me to photograph numerous theme parks across three continents.

THE INVISIBLE ART OF EDITING, AND WHAT AI CAN NEVER SEE

HM: Valerio, there’s a well-known saying among editors that photographers are often the worst judges of their own images. What’s your experience?

VV: (laughs) It’s true more often than not. Photographers can be great at editing other people’s work, but when it comes to their own, it’s hard to detach emotionally. There’s too much memory attached to the moment. You remember how hard it was to get the shot, how meaningful the situation felt—things that don’t always translate into the final image. That’s why the editing process is so important, and ideally, someone else should be involved.

HM: You must receive thousands of images for assignments or pitches. What does your editing process look like?

VV: Yes, it’s a lot. And I’ve developed a method that works well for me. First, it depends on the format. Some photographers send me PDFs, others use WeTransfer. PDFs usually have a pre-set layout—the photographer has imposed their own order, chosen a “hero image,” written captions. But often they get it wrong. The cover image rarely grabs attention the way it should. Photographers sometimes hide the best photo mid-document, thinking they’re “building up” to it. That doesn’t work. You need your strongest image first. It sets the tone.

I actually prefer WeTransfer—raw files in sequence. No imposed logic. That way, I come in without bias.

HM: And then what happens?

VV: I do a two-step edit, when I have the time. First, I go through all the images quickly—one or two seconds per photo. No overthinking. I just absorb them visually. Then I walk away. I do something else entirely—sleep on it, ideally. Then, when I return, I ask myself: What do I remember? What visuals stayed with me? The ones that lingered in my subconscious are usually the strongest—they have a lasting visual power that overrides technical analysis.

Then I refined it. I go through again, this time rationally. I look at the captions, the narrative arc. I add in contextual images that might be less visually striking but essential for storytelling. And finally, I adjust the sequence, mood, and pacing. So it becomes a three-step process: instinct, memory, then logic.

Opening double spread of the 10 page portfolio by Daniel Ochoa de Olza / Panos on the “holes” in the US-Mexico wall.

HM: That’s a beautiful way of editing—guided by memory and intuition.

VV: It works well for me. I’ve also picked up tricks from other editors. One technique I sometimes use is shrinking all the images down to thumbnails—tiny icons on the screen. Then I just glance at the grid and pick what visually pops at that scale. If something holds up compositionally when it’s small, chances are it has a strong graphic impact. But I use this method sparingly. It’s more a test than a system.

HM: You mentioned speed. How fast do you work?

VV: Very fast—sometimes alarmingly so to others. (laughs) I can go through 400–500 photos quickly and still come away with a strong selection. It’s about trusting your visual instincts. But—and this is crucial—I never finalize an edit before seeing all the images first. You can’t judge without seeing the whole picture. Fast judgment, yes—but only after full exposure.

HM: Let’s talk about the future. How do you see the role of the photo editor evolving, especially in the age of AI?

VV: It’s a serious question. AI is already reshaping the field, and it will continue to do so—quickly. There are going to be tools where a journalist can simply upload their text and an AI will generate a selection of stock images that match the story. The results won’t be perfect at first, but they’ll be good enough for many publications—especially those prioritizing speed and cost. The risk is obvious: if the decision-makers don’t see the added value of a human photo editor, they’ll say, “Why not just let the bot do it?”

HM: And what do you say to that?

VV: I think they’re missing the point. Yes, AI will assist in photo research. That part of the role—scrolling through agency databases, matching keywords—will be increasingly automated. But that’s not the essence of editing. Real photo editing is about relationships. It’s about knowing the photographer, the context, the story behind the story. It’s about knowing what isn’t in the caption, and asking for that image you suspect exists but wasn’t sent.

Also, assigning photographers—that will always be human. Choosing the right person for the job requires intuition, emotional intelligence, and logistical knowledge. AI can’t replicate that.

HM: Are you already using AI tools in your workflow?

VV: Yes, cautiously. One of the most useful tools right now is AI upscaling. If a photographer sends low-resolution images from the field and we suddenly need them for print, but they’re already on another assignment and unreachable, I can use AI to increase the resolution for printing. That’s a real benefit.

But there’s also the risk of unnoticed manipulation. AI-generated or AI-altered images can be incredibly convincing, and we currently lack tools to detect them reliably. Unless you get the RAW files, and even then—it’s not foolproof. I live with the anxiety that one day I might publish an image that was AI-generated and not know it.

HM: So, in your view, where is the line between useful automation and artistic compromise?

VV: The line is in the intention. Tools like AI should support the work, not replace the soul of it. A photo editor isn’t just someone who “picks pictures.” We’re curators of meaning, caretakers of truth, and collaborators in how stories are visually told. That’s something no algorithm can do. At least, not yet.

PHOTOGRAPHY, AI, AND THE FUTURE OF VISUAL STORYTELLING

HM: AI is a huge topic in photography and publishing. From your perspective as Director of Photography at GEO, how do you see it impacting your work today?

VV: It's both exciting and alarming. The impact really depends on how it's used. On the one hand, AI is already embedded in our daily routines. For instance, Gmail offers writing assistance that pops up all the time. Sometimes it wastes time, but other times it's surprisingly helpful. Recently, I received a very long project pitch from a photographer, and I thought, "This is unclear—what should I ask him?" So I asked the AI to read it and suggest questions. It came up with four. One of them I had already thought of, another was a very good idea I hadn’t considered. It helped me keep the conversation going with the photographer.

HM: So AI is already a kind of assistant in your editorial process?

VV: Yes, but it works best when it's anchored to real information. If I give AI a well-designed proposal, or a specific email, it can help refine the process or anticipate questions. It's rarely perfect on the first try, but it can be a great collaborative tool.

Example of the layout of the 10 page portfolio by Daniel Ochoa de Olza / Panos on the “holes” in the US-Mexico wall.

HM: What about more advanced uses of AI? Are you seeing any significant changes?

VV: One of our trainers recently demonstrated how AI can now take over your computer—open apps, make bookings, generate plans. He used it to organize an entire 10-day family holiday in Italy: hotels, restaurants, PDFs, confirmations. All automated. And it worked. Only one hotel had closed in the meantime. That’s amazing. It made me think: could AI help optimize a photographer's time in the field? Calculate the best route, the right hour for light, how much time to spend in each location. The potential is massive. But for now, it’s also very time-consuming. You need to invest time to get meaningful results

HM: And the pace of change?

VV: That’s the most destabilizing part. It evolves so fast. You can spend a week learning one tool only to find it's obsolete a month later. This has big implications, especially for education. How do schools prepare students for a world where the tools they learn may be outdated by the time they graduate?

HM: Let’s switch to your editorial work. Could you walk us through some recent stories you're especially proud of?

VV: Sure. One that comes to mind is a portfolio by George Steinmetz. He’s been photographing the global food industry for decades. His archive is vast—landscapes, industrial farms, inside factories. So when he sent me this material, I proposed something very focused: "Let’s do one landscape photo per country. Just the helicopter views." That simple edit gave the work a new coherence. The grand scope of the project remained intact, but the selection told a tighter story.

Example of the layout of the 10 page portfolio by Daniel Ochoa de Olza / Panos on the « holes » in the US-Mexico wall.

HM: That’s a very editorial solution to a sprawling body of work.

VV: Exactly. Another story I love is about the U.S.-Mexico border. We’ve seen many projects on this, but this photographer, Daniel Ochoa de Olza, focused not on the wall itself, but on where it stops — where it opens, or just fades into the landscape. The surreal aspect of a border that starts and ends in the middle of nowhere. The story became not just about politics, but about absurdity. These quiet, powerful images spoke volumes.

HM: And what about assignments?

VV: There are two types of stories we produce: the first are those pitched by photographers. One assignment I’m particularly proud of involved the last Indian elections in 2024. We collaborated with Arko Datto, who aimed to document the transportation of voting machines to remote areas. By law, no voter can be more than two kilometers away from a polling station, which means officials journey into jungles, deserts, and mountains, sometimes just to reach a family of ten. The production was logistically challenging—we financed three separate trips—but the outcome was three compelling stories that highlighted an essential truth: democracy requires a physical commitment.

HM: That’s a beautiful way of putting it. And very GEO. What about the second kind of assignment?

VV: It’s when one of our journalists pitches a story. In this case, before organizing the production, I have to select a photographer for the story. One of our experienced journalists aimed to document a small community in a remote area in the far east of Turkey. I needed to find a photographer who could accompany her—a professional with a distinctive visual style that would capture the isolation of the location, while also being able to work quickly and connect with the local community. After discussing it with our editors, as we collaborate on every decision at the magazine, I chose to work with Emily Garthwaite. I had previously partnered with her on other stories and felt she would be a great fit for this project. We’re excited to publish the story in May!

HM: Let’s zoom out a bit. Where do you see the future of visual storytelling heading?

VV: I don’t think anyone can say with confidence where it’s going. People who act like they know? I don’t know where they get their certainty. Maybe people will go back to print, like they did with vinyl. Maybe a new tech will come along and upend everything.

What I do know is this: GEO’s role will always be to tell true stories, deeply reported and visually rich. Even if younger generations are more attracted to synthetic or AI-generated visuals, there will always be people who want to understand the real world. There will always be readers who value trust, professionalism, and perspective. That’s what we offer.

HM: And the role of the photo editor?

VV: The photo editor's role is under threat, yes—but it’s also evolving. Photo research can be automated. But real storytelling? Understanding the context, guiding a photographer, shaping a narrative—those things can’t be done by a bot. Not yet. The challenge is to stay human, stay curious, and adapt. That’s how we survive.

HM: Valerio, you've lived so many lives—consultant, photographer, artist, editor—and it really shows in the way you think and speak about photography. This felt like a masterclass in how the world of editing and publishing is evolving. Thanks so much for taking the time and sharing your wisdom with us,

VV: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.