Eugene Tapahe: Healing and the Jingle Dress by Brian Byrd

Brian Byrd is a freelance photographer with more than two decades of experience advancing communication as a catalyst for social change. He serves on the board of directors for the Overseas Press Club of America and the advisory board for WITNESS, a global NGO founded by musician Peter Gabriel that uses video and digital technology to document human rights violations.

Art Heals: The Jingle Dress Project

While wandering through this year's Association of International Photography Dealers (AIPAD) show in New York City, it's easy to become overwhelmed by the vast number of photographs on display. Yet among the visual cacophony, the Monroe Gallery booth stood out as one of the few to highlight the work of Native American artists. Eugene Tapahe's photographs from his Art Heals project commanded attention—not merely for their striking colors juxtaposed against nature's beauty, but for the profound story they tell. These images, featuring jingle dress dancers in magnificent landscapes, invite viewers into a space where cultural heritage, environmental connection, and healing converge in visual harmony.

Togetherness, Sisters, Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah, Goshute and Timpanogos, 2023

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

Walking in Beauty

"I draw inspiration from my Diné (Navajo) traditions and modern experiences," said Tapahe. "My work reflects the beauty and resilience of Native American culture. I strive to unite these two worlds in my concepts while transcending worldly uncertainties."

At the core of Tapahe's artistic vision is the traditional Navajo philosophy "to always walk in beauty," a principle that guides both his creative practice and personal journey. Through various visual mediums—photography, video, printmaking, installation, and mixed-media sculpture—Tapahe creates a delicate balance between past and present, using subtle contrasts, natural colors, and contours to offer unity, hope, and healing in a world often marked by disconnection.

In the early months of 2020, as the world retreated into isolation, the Diné (Navajo) artist found himself at a painful crossroads. His art shows were canceling one by one, and personal tragedy struck when he lost his aunt to COVID-19. "I felt like I was broken," he recalls. "I felt like there was nothing good going to happen."

Then came the dream that would change everything.

Tapahe describes a peaceful vision where he sat in a Yellowstone meadow watching grazing bison. The tranquility was interrupted by the distinct sound of jingles—and suddenly, beautiful jingle dress dancers appeared, performing alongside the bison. He awoke with a profound sense of healing and hope, immediately sharing his vision with his family.

"This dream is telling me that we need to take the jingle dress to the land, to heal the land," Tapahe told his wife and daughters. "And if we heal the land, we're going to heal the people."

Strength and Dignity, La Push Beach, La Push, Washington

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

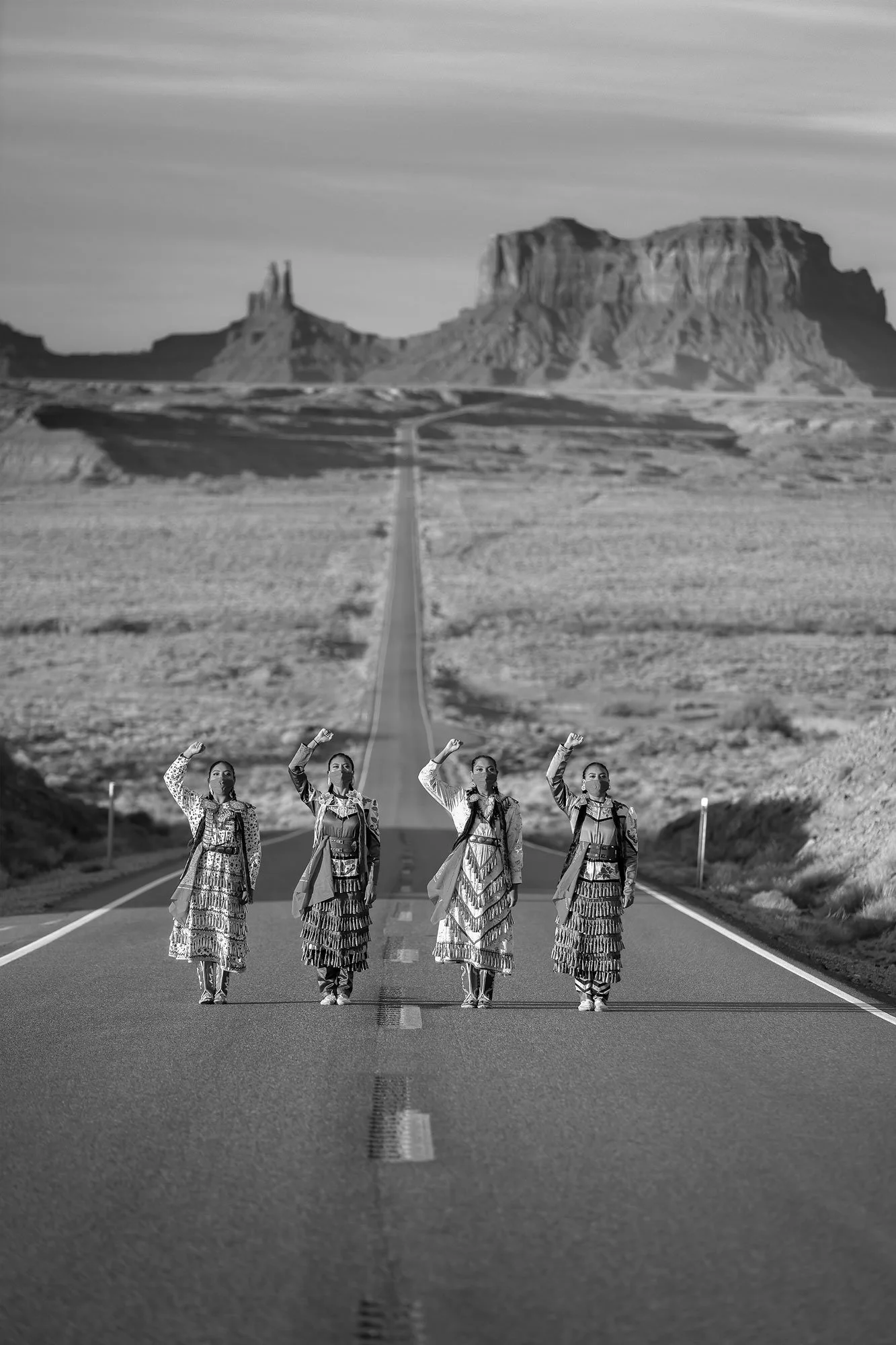

Solidarity, Sisterhood, Monument Valley, Arizona, Dine, 2020

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

The Reclamation Project

What began as a dream has evolved into Art Heals: The Jingle Dress Project, a transformative artistic journey spanning over 25,000 miles across America's landscapes. Tapahe, together with four Diné women—his daughters Erin and Dion Tapahe, along with Sunni and JoAnni Begay—have traveled to numerous National Parks and Monuments to document the healing dance in spaces where Native ancestors once lived. The four dancers symbolize the four worlds in Navajo culture, powerfully asserting Indigenous presence on ancestral lands.

The 1st World, Black World (Nihodilhil), is where spiritual and insect beings lived until conflict drove them away. In the 2nd World, Blue World (Nihodootlizh), birds and animals faced similar discord, forcing another migration. The 3rd World, Yellow World (Nihaltsoh) with its rivers ended when Coyote – the trickster - caused a great flood. Today's 4th World, White or Glittering World (Nihalgai or Ni'hodisxóstłʼish) is where Navajo people now live, marked by sacred mountains and celestial bodies.

"These native lands and the national parks, they were prime spots for Native people to live," Tapahe explains. The project became a reclamation of these spaces through art, dance, and spiritual connection.

This project builds on Tapahe's history of artistic activism. In 2016, he traveled to Standing Rock, North Dakota, standing alongside water protectors against the Dakota Access Pipeline. The experience culminated in his self-published book Standing for Unity: The Standing Rock Movement, documenting the historic gathering that brought together thousands from hundreds of different cultures and tribes around the world united by the rallying cry: "Mni Waconi!" (Water is life!).

Crossing Generations, MMIW, New York, The native land of the Mohican, Wappinger, and Munsee Lenape people

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

Listen to the Trees, Central Park, New York, The native land of the Mohican, Wappinger, and Munsee Lenape people, 2020

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

“We’re Still Here”

The jingle dress itself serves as a perfect metaphor for the project's mission. Originally from Ojibwe tradition, the dress with its hundreds of metal cones creates an unmistakable sound that commands attention.

"There's no way you can be quiet in a jingle dress," Tapahe says. "It just calls for attention. And everywhere we went, that's what it did."

This visibility is intentional and necessary. As the dancers have discovered through their travels, many Americans are unaware of contemporary Native presence. "I've heard so many comments like, 'Oh, do you live in a teepee? Oh, I didn't know you still exist. I only read you in history books,'" shares one of the dancers.

Through their performances and photographs, the project makes a clear statement: "We're still here."

We Are Still Here 2, Monument Valley, Arizona, 2020

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

Granite and Grace, Yosemite National Park, California, Home of the Nyyhmy (Western Mono Monache) people, 2020

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

A Multidimensional Art

For Tapahe, who completed his MFA at Brigham Young University in 2024, the project represents an expansion of artistic expression beyond his background in graphic design and photography.

"Art comes from deep inside us, in our hearts and who we are personally," he explains. "We don't have just photograph art, but we have the art of dance. We have the art of music. We have the art of nature. When they all come together for a spiritual reason, it heals."

This holistic approach reflects Tapahe's unique life journey. During his first years on the Navajo Nation, he and his grandmother lived off the land, practicing traditional ways. Tapahe “learned at an early age the importance of respecting, preserving and protecting what is sacred—the land, water and nature," as described in his artist statement. It was only later that he would unite this deep cultural connection with formal education in graphic design, journalism, and fine arts.

His decision to pursue art full-time came after a pivotal moment ten years ago. Leaving behind the security of stable employment, Tapahe initially struggled to find his photographic voice. It was his wife Sharon who provided the breakthrough advice: stop taking photos he thought others would like, and instead listen to his own heart to tell his authentic story.

This authenticity has earned him numerous accolades, including—for the first time in any Indian Market's history—Best of Show awards for photography at both the Cherokee Indian Market and The Museum of Northern Arizona. His work now graces the collections of prestigious institutions including The Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and museums across the country.

Indian Land, Palm Springs, California, The native land of the Ɂívil̃uwenetem Meytémak people, 2021

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

Strength In Unity, Tetons National Park, The native land of the Shoshone, Bannock, Gros Ventre, and Nez Perce People, 2021

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

Transforming the Dancers

Perhaps the most profound impact of the project has been on the dancers themselves. These young women—who Tapahe describes as "not professional models but strong examples of Native American women today"—have experienced remarkable personal growth through their participation.

"I felt more empowered. I felt more connected to the community. I feel more confident in sharing the things that I'm passionate about, like Native rights and representation," shares one dancer.

Another dancer notes how the project helped her recognize the importance of understanding generational trauma and embracing her identity as an Indigenous woman: "I didn't learn about generational trauma until my freshman year in college, and I didn't realize how important this is to my identity and who I am."

These jingle dancers—two pairs of Diné sisters—have devoted countless hours to make the project a reality. Their commitment runs deeper than the photographs; they have performed their cultural dances internationally in countries including Germany, Switzerland, Brazil, New Zealand, Samoa, Tonga, and China. As Tapahe notes, "They know the importance of connection with the land as Native people and were raised to respect the traditions of their ancestors."

For Tapahe, witnessing this transformation has been especially meaningful. "I could see how much confidence they gained, how much empowerment they had, how much more respect they have for their culture and their traditions and for who they are," he says. He speaks candidly about the challenges they face: "From the moment you took your first breath into this world, you already had two strikes against you. One, you're a female. Two, you have brown skin."

Four Worlds, Teton National Park, Wyoming, The native land of the Shoshone, Bannock, Gros Ventre, and Nez Perce people, 2020

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

Remember our Sisters, MMIW, Bonneville Salt Flats, UT, Goshute and Timpanogos, 2020

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

The Metaphor of the Jingle

As the project progressed, Tapahe discovered a powerful metaphor that encapsulates its message. While handling one of the dresses, he noticed something profound: "I put my hand on one of the jingles, and I shook it. That one jingle didn't make any sound."

This observation crystallized the project's deeper meaning: "But together, they have the power to heal. As human beings, if we're able to unite ourselves and our prayers and make a beautiful sound as the jingle dress does, we could be powerful."

In a world increasingly divided, Tapahe's Art Heals project offers a resonant reminder: "How much more we could learn from one another. If we could just listen to each other."

Nizhoni (Beautiful), Monument Valley, Arizona, 2020

©Eugene Tapahe, Courtesy of Monroe Gallery

A Timely Message

Sid and Michelle Monroe, owners of the Monroe Gallery, explained the deliberate timing of Art Heals: The Jingle Dress Project, which opens just after July 4th. “The holiday supposedly celebrates Freedom, Independence, and the statement that all men are created equal,” they said. “Yet as a result of the Declaration of Independence, a flood of white settlers moved onto Indigenous lands. As the white settler population grew and the U.S. expanded, Indigenous populations dramatically decreased, along with tribal homelands and cultural freedoms.”

Through his work, Tapahe also aims to raise awareness about the disproportionately high rates of violence and missing persons experienced by Indigenous women. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) crisis represents one of the most devastating issues facing Tribal communities today, with alarming reports of abduction and murder that often receive insufficient attention from mainstream media and law enforcement.

“In the process of photographing, I found one overarching metaphor,” Tapahe explains. “One jingle doesn’t make a sound, but together, they have the power to heal. If we’re able to unite as the jingle dress does, how powerful we could be, and how much more we could learn from one another, if we could just listen to each other.”

The jingle dress—with its many individual metal cones working together to create healing sounds—becomes a powerful symbol for how unity can address even the most profound challenges facing Indigenous communities and the broader society.

Eugene Tapahe's work is included in the collections of The Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, The Birmingham Museum of Art, The Toledo Museum, and numerous other prestigious institutions. The Art Heals: The Jingle Dress Project exhibition at Monroe Gallery runs from July 5 through Santa Fe's Indian Market weekend in mid-August. For more information, visit the Monroe Gallery website.