Bearing Witness: A Conversation with Donna Ferrato

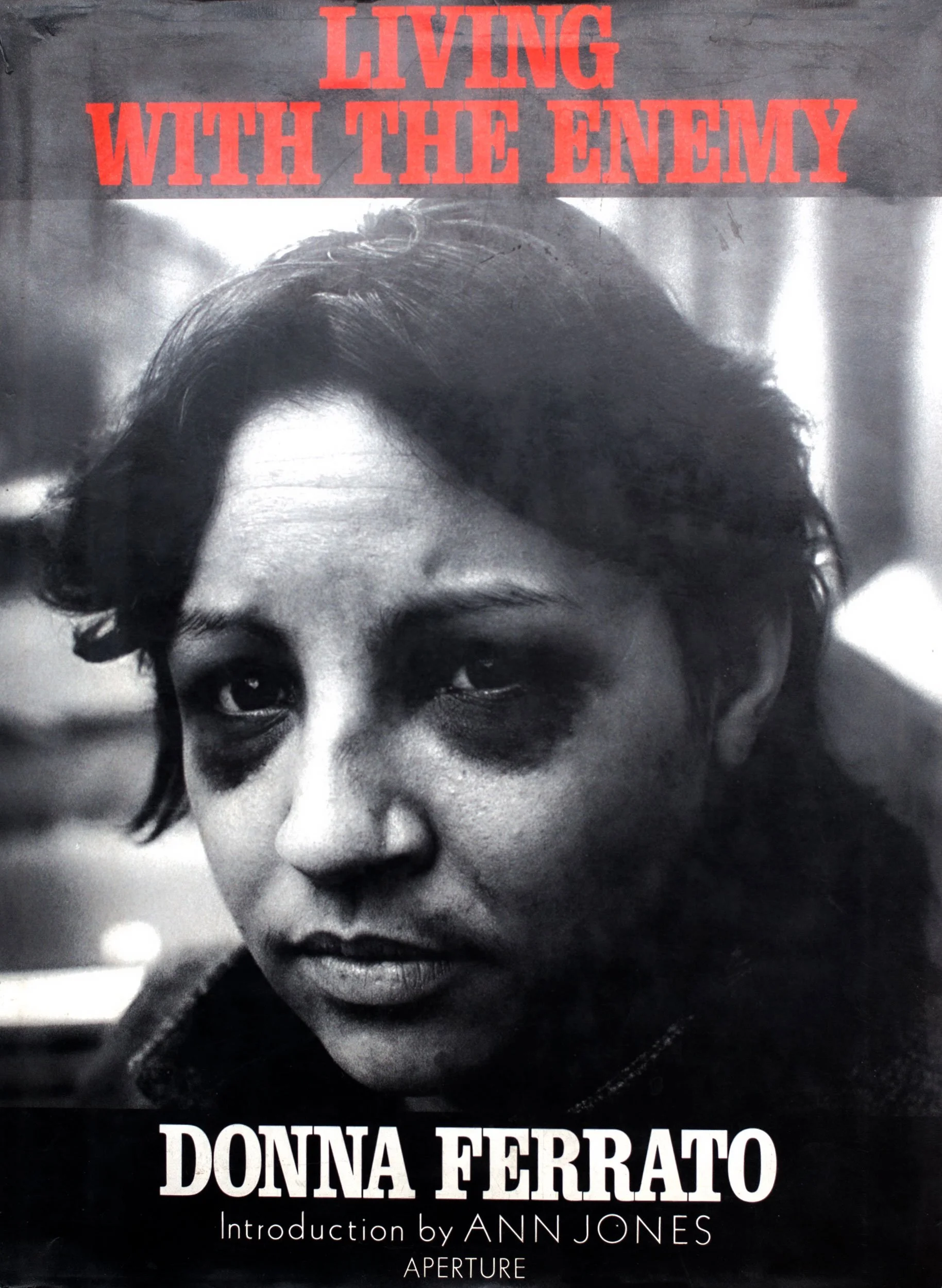

Donna Ferrato is a fearless photojournalist who has redefined how the world sees domestic violence through her groundbreaking work. Her seminal book Living With the Enemy— published by Aperture and reprinted four times—sparked a global reckoning, exposing the hidden realities of abuse and igniting conversations that continue to drive change.

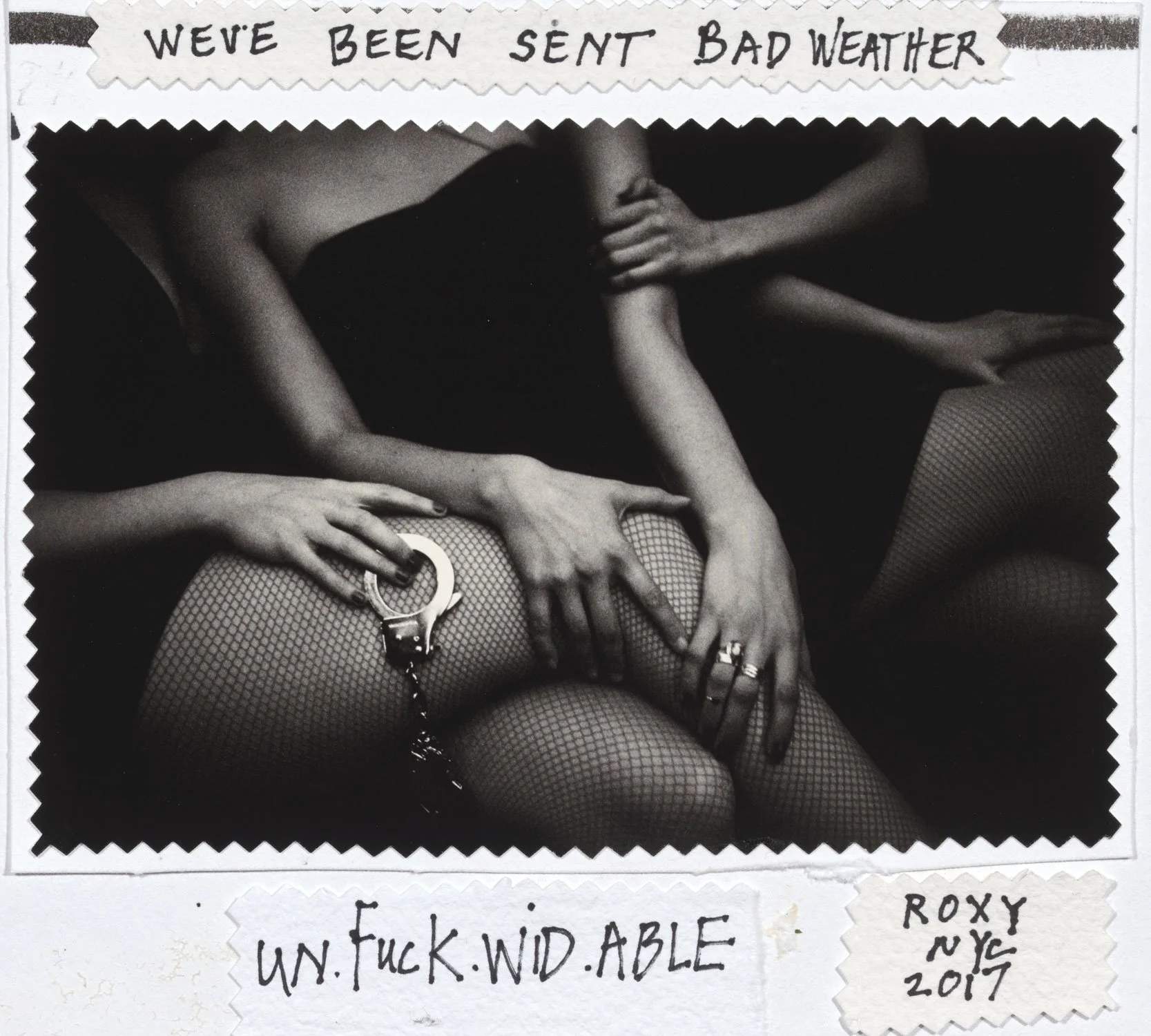

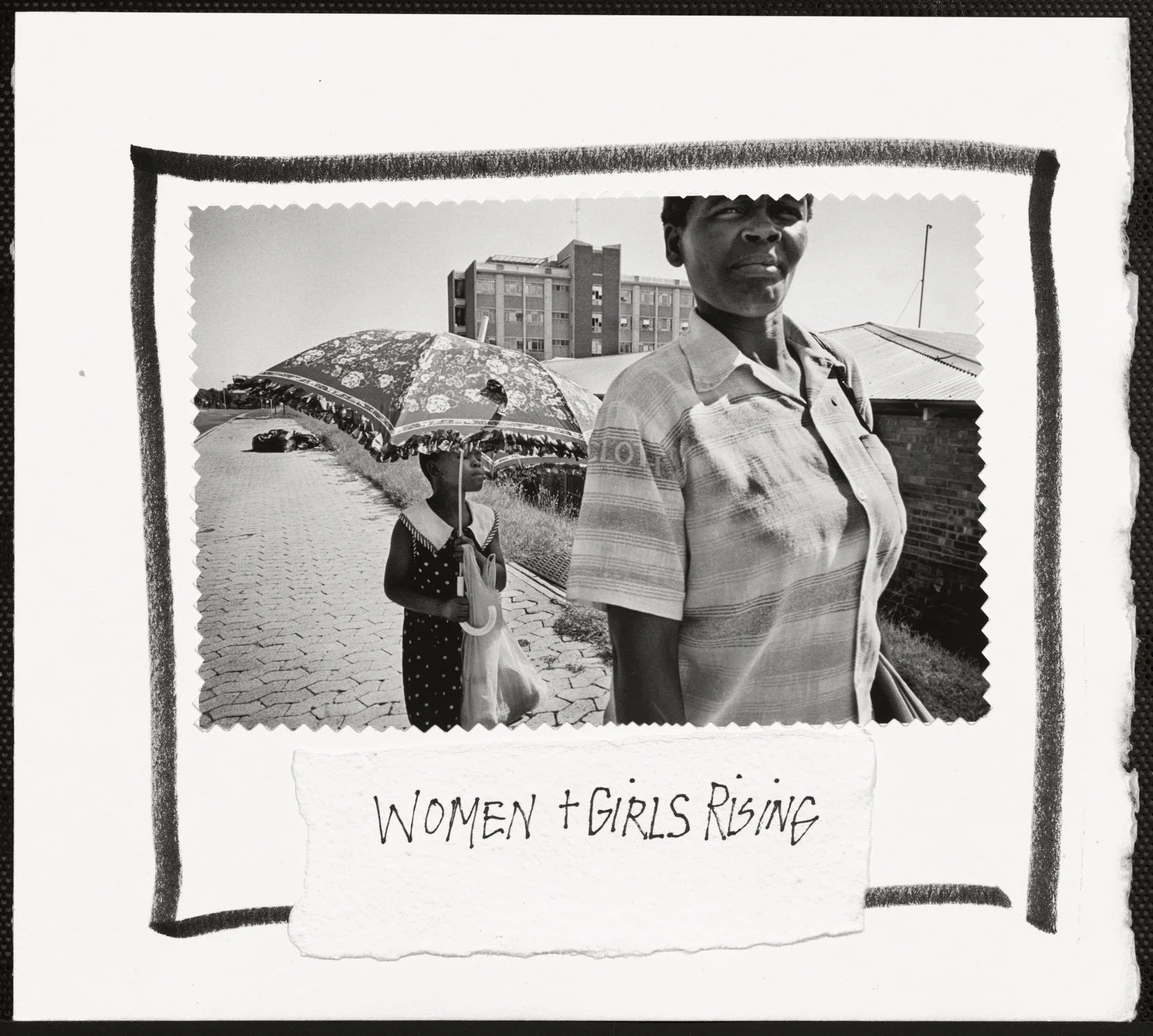

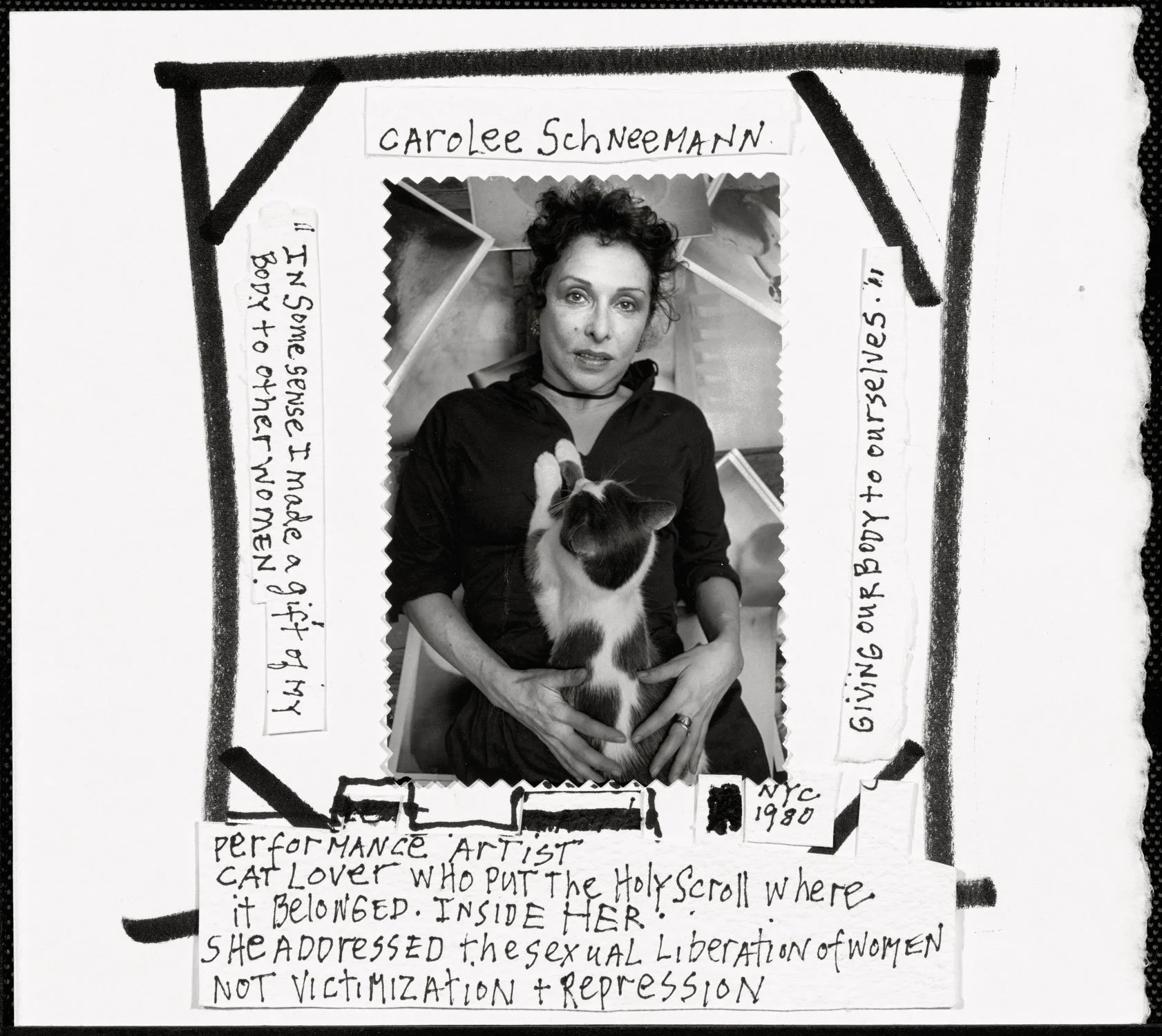

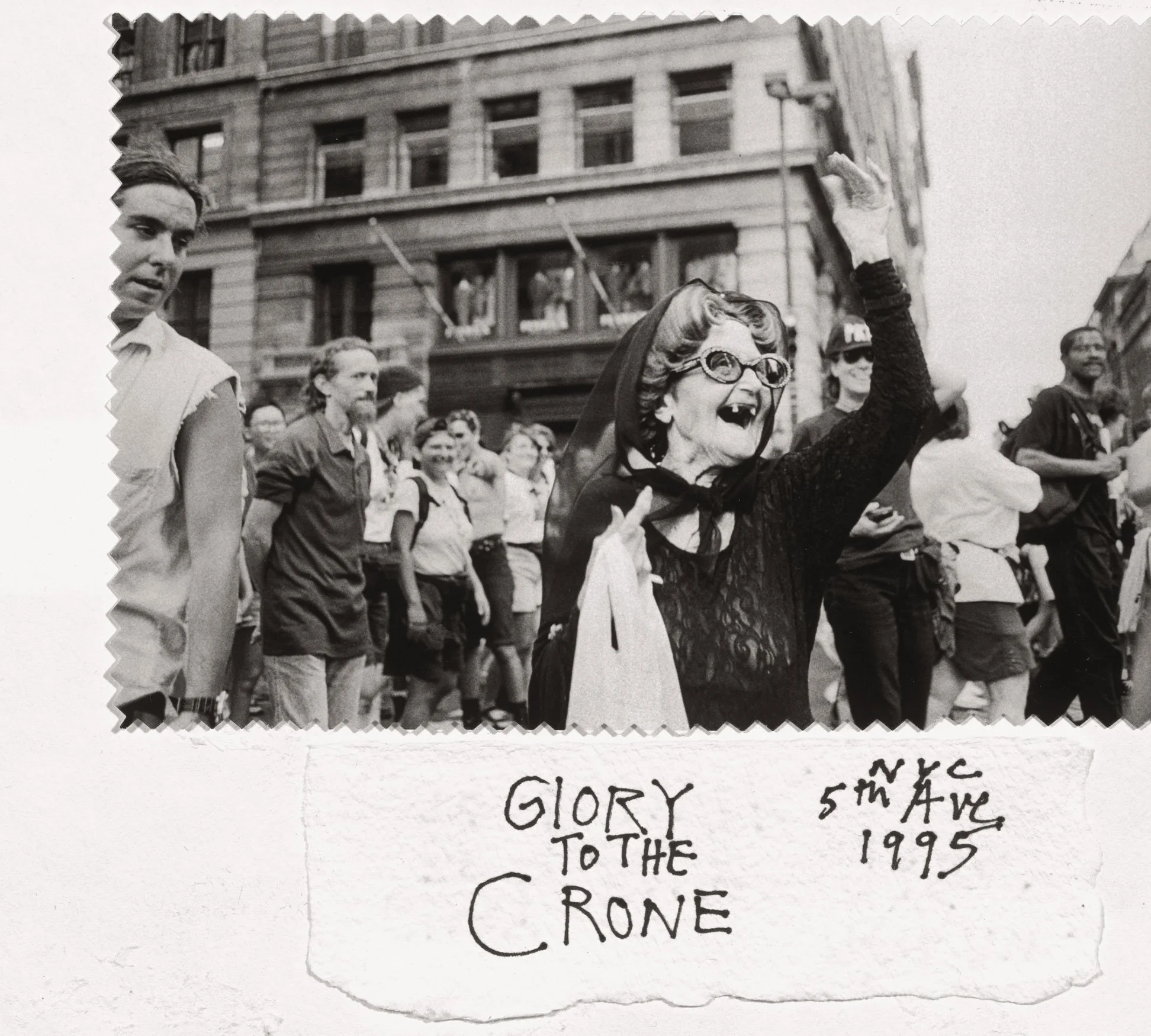

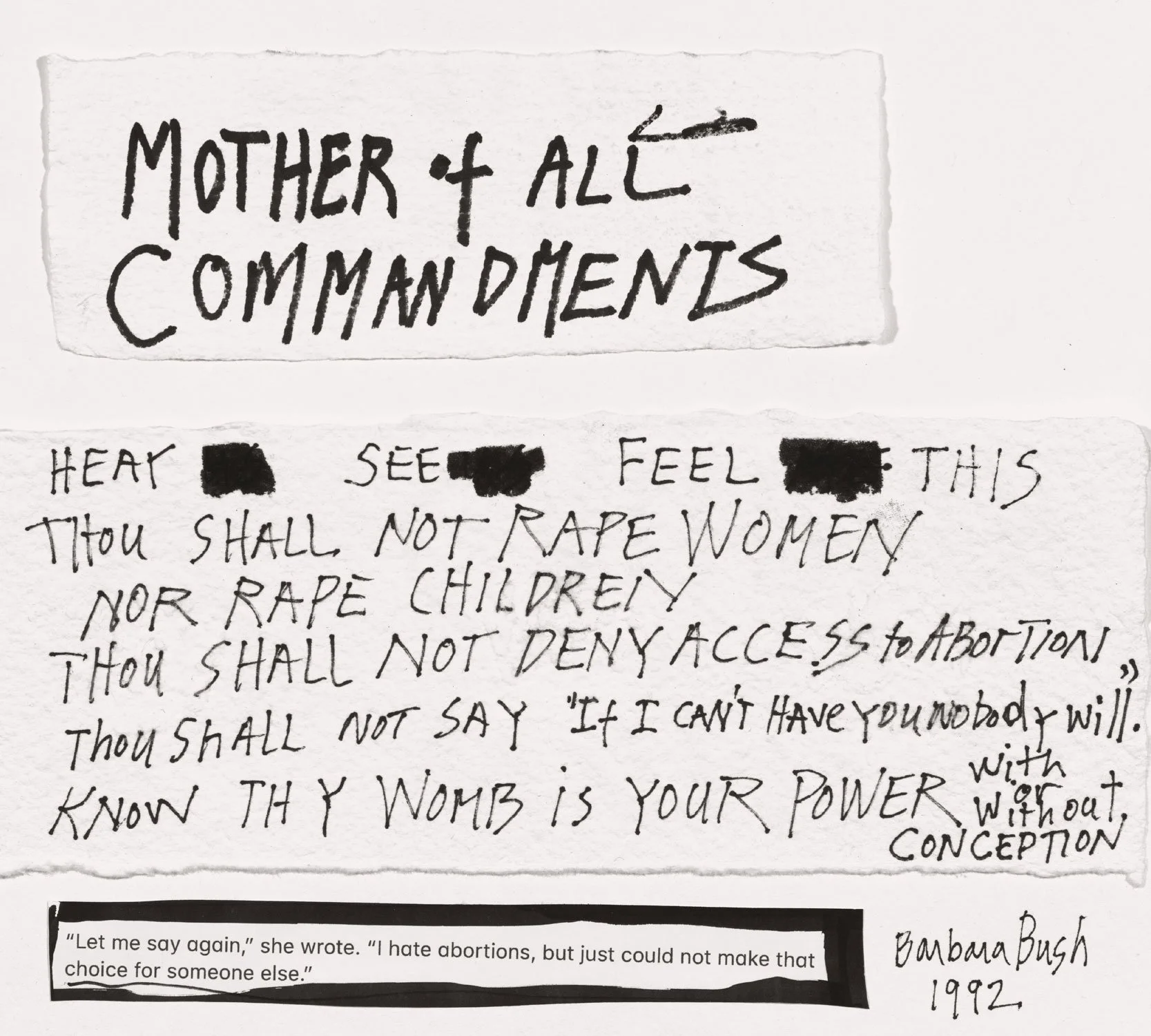

Her latest work, Holy (powerHouse Books, 2020), is a passionate call to action, proclaiming the sacredness of women’s rights and their power to be the authors of their own destiny. Through it, Ferrato continues her lifelong mission of wielding the camera as a tool for justice.

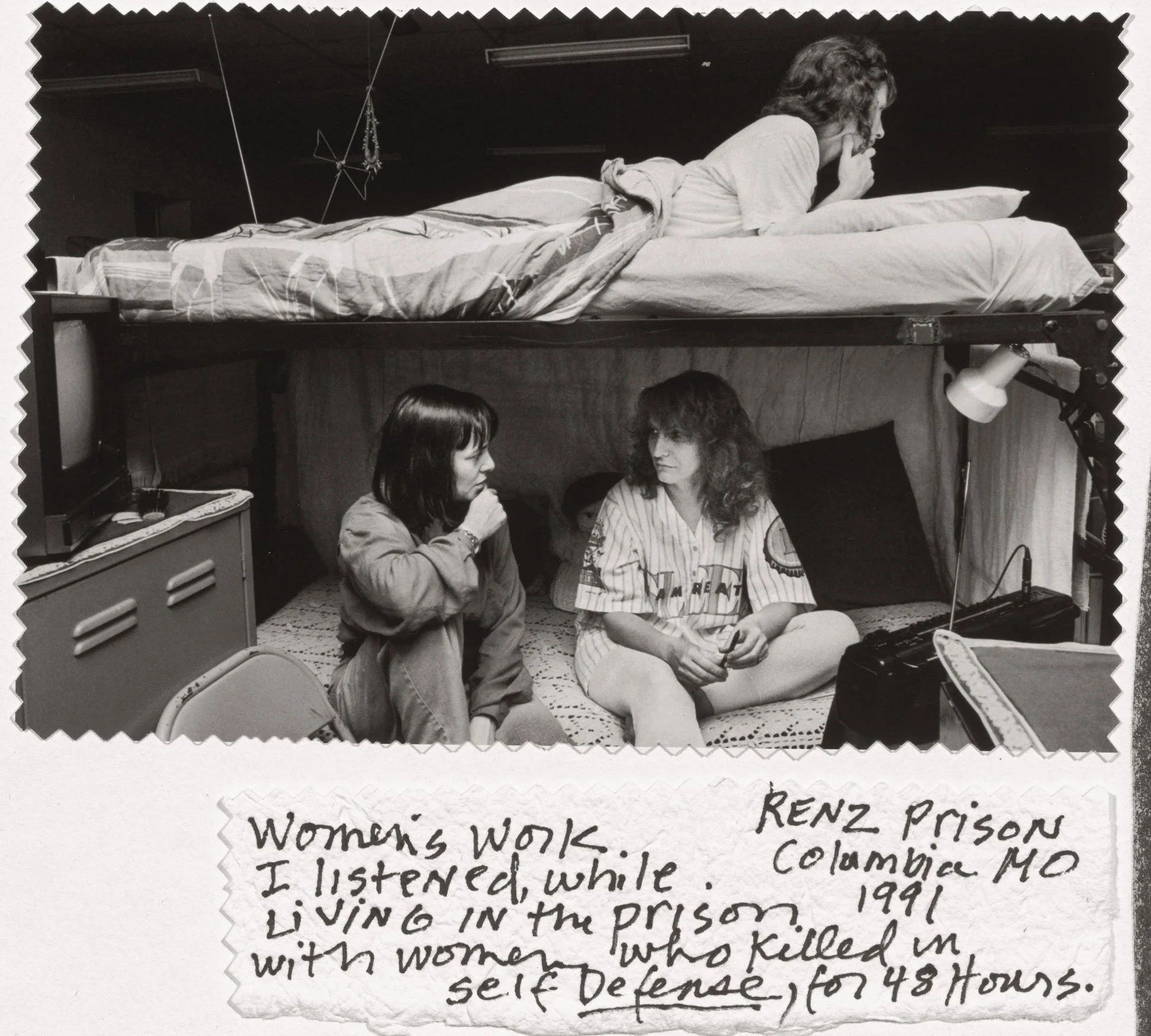

In 2021, Ferrato received a grant from the Mayor’s Office to End Gender-Based Violence to build and install a public art installation on a human scale in the form of a prison cell sculpture of mirrored steel which symbolized a portal into the lives of criminalized survivors of domestic violence.

Ferrato's work has been recognized with numerous prestigious honors, including the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography, the Robert F. Kennedy Award for Outstanding Coverage of the Plight of the Disadvantaged, the IWMF Courage in Journalism Award, the Missouri Medal of Honor for Distinguished Service in Journalism, Artist of the Year at the Tribeca Film Festival, and the Look3 Insightful Artist of the Year. In 2008, New York City declared October 30th “Donna Ferrato Appreciation Day,” and in 2009, she was honored by the judges of the New York State Supreme Court for her tireless advocacy for gender equality. In 2025, she was awarded an honorary doctorate from John Jay College of Criminal Justice for her lifelong commitment to justice, truth, and the transformative power of photography.

Ferrato's photographs are held in major institutional collections including the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Library of Congress, and the International Center of Photography in New York City, as well as in private collections such as those of Celso Gonzalez-Falla, the Marrus Family Fund, Keri Jackson and Adrian Kunzel, Ann and Alex Russ Family Fund.

She is represented by the Daniel Cooney Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Represented in NYC by Two by Two Media

New York, New York

Email gigi@gigistoll.com

Professor Shonna Trinch / Seeing Rape class John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Portrait of Donna Ferrato © Alex Patterson Jones 2024

HM: Hello, Donna. First off, congratulations on the prestigious honor you received from John Jay College of Criminal Justice in May. That must have been incredibly moving. Would you like to tell us more about it?

DF: Thank you, Amnon. It was an emotional experience—one I deeply wished my parents had been alive to witness. Still, I was grateful that my daughter, Fanny, and two dear friends, GiGi Stoll and Dorie Hagler, were there to photograph the moment—just as my father would have.

As the ceremony began, President Karol Mason introduced me to a sea of Black and Hispanic graduates—thousands of them, a powerful and diverse audience. She spoke of how my work has shed light on the often-hidden world of violence and sexual assault, calling me an advocate for justice. She shared that many students had relied on my book to better understand domestic violence, and that it had helped them find the strength to confront their struggles.

Then, on a massive screen overhead, a video played featuring the courageous survivors who opened their lives to me—sacrificing their privacy to help others find hope and resilience. Afterward, Professor Shonna Trinch walked up to me, kissed me in front of the crowd, and placed a heavy white satin collar around my shoulders. The audience erupted in applause—it was overwhelming, breathtaking.

To be honored by such a prestigious institution dedicated to criminal justice was the pinnacle of my career as a photojournalist. I’ll never forget it.

Professor Shonna Trinch, Department of Anthropology and Co-Founder of the Seeing Rape theatre series © Donna Ferrato 2025

Professor Karen Kaplowitz, President of the Faculty Senate, with President Karol Mason © Donna Ferrato 2025

HM: Powerful. When was Living with the Enemy first published? I remember the impact it made.

DF: It was published by Aperture in 1991. My partner, Welsh anti-war photographer Philip Jones Griffiths, designed it. It was reprinted four times before I reclaimed the rights. Today I'm collaborating with Dr. Lauren Walsh and Nancy Zhang on a graphic novel inspired by the original Living with the Enemy book.

Donna's graduation speech © Dorie Hagler 2025

HM: Colleges clearly continue to keep an eye on you. But tell us, why did you choose this subject? You could have done fashion or something more glamorous. Why pursue something so painful?

DF: I couldn’t look away. The pain I witnessed was too real.

Early in my career, I explored the many permutations of love. But in truth, it was my father who prepared me—intentionally or not—to seek out the truth of what happens behind closed doors.

My dad was a surgeon. He healed people with a scalpel, but I have no doubt he trained me, in his quiet way, to use a camera to find abuse, perhaps help people to heal.

My Dad, the heart surgeon, kept vigil over his father, feeling broken hearted. Cleveland, OH © Donna Ferrato 1981

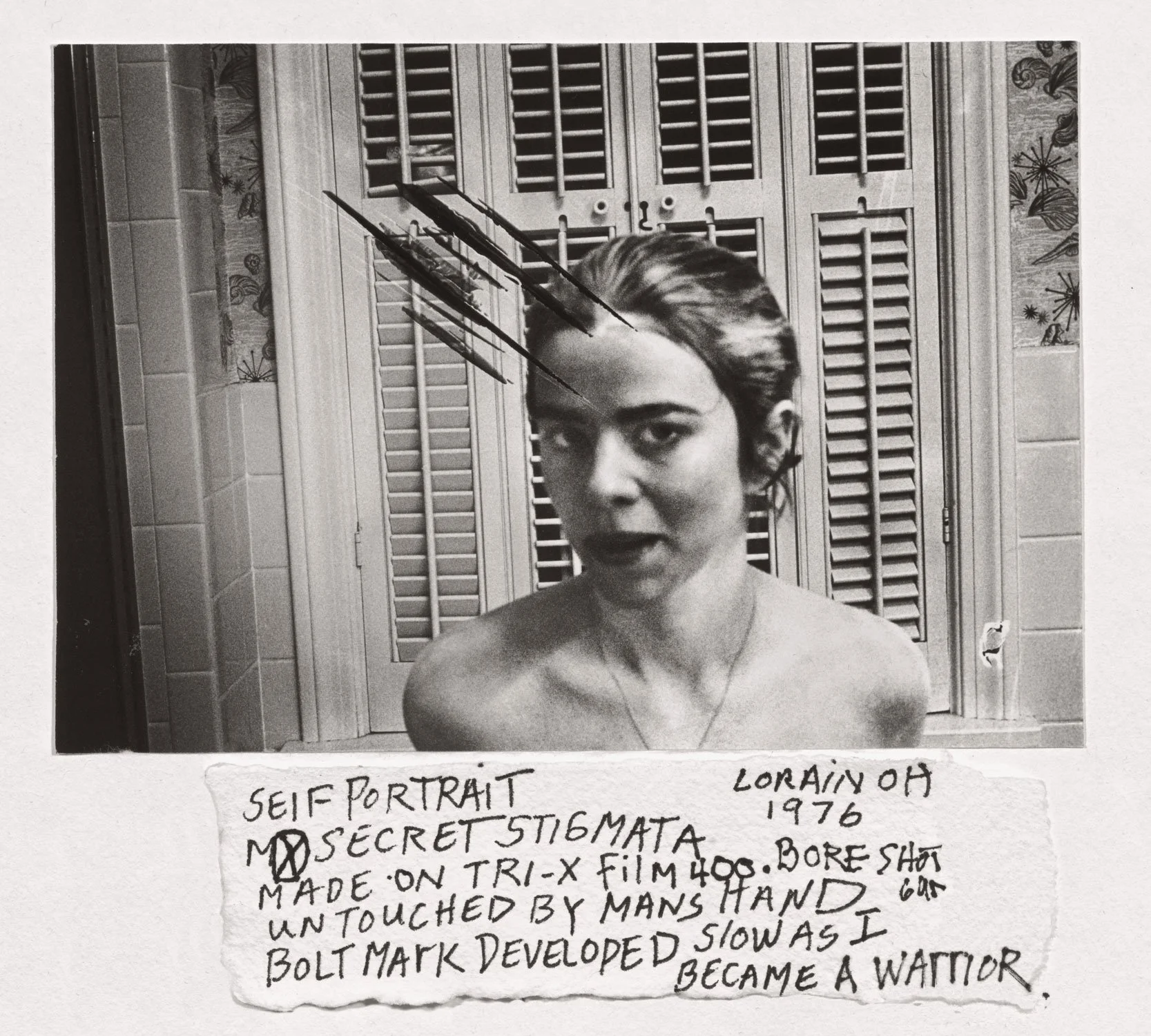

When I was growing up in Lorain, Ohio, Dad would leave newspaper clippings on the breakfast table—stories about men who beat their wives or children. In the margins, he scribbled comments in his tight handwriting. I never asked why those stories mattered to him.

Decades later, when I began working for LIFE Magazine on assignments eerily similar to those old clippings, he started to open up. In pieces. In moments. He told me, quietly, about the abuse he had witnessed in his childhood.

Grandpa and Grandma back together. Grand Junction, CO © Donna Ferrato 1975

His parents—my grandparents—were proud, hardworking Italian immigrants. Grandma made the best nonna pizza in Cleveland. People were crazy for it. Grandpa was a tool and die maker who brewed his wine and grappa in the basement. He was cheerful, even charming. Grandma, though, always seemed distant. Sad.

It was hard to get close to her.

And as I grew up, I was too caught up in other people’s pain to question the disorder in my own house. My father and my brothers have suffered because nothing so personal was ever discussed openly. I am a photographer because I believe that photos can be used as tools for change. I see better now that if we are able to unchain ourselves from the past by being honest and loving, even forgiving, we might be able to heal the old scars of generational trauma.

Dr. Peter Ferrato, his mom, Antoinette, his son Louie, his dad, Domenic, making pizza. Lorain, OH © Donna Ferrato 1969

Grandma. Cleveland Hopkins Hospital © Donna Ferrato 1981

Dad and Grandma with Grandpa before he died. Cleveland Hopkins Hospital © Donna Ferrato 1981

HM: That’s a remarkable origin story. How else did he prepare you?

DF: Here's a story for you.

I was four years old. My mom, dad, and I were living in a Quonset hut in the Adirondack Mountains. One chilly morning, Dad took me for a walk. We stopped at the edge of a rushing meltwater creek, and he said, “Let’s play a game.”

He rolled up his pants, stepped into the icy stream, and called out, “Jump into my arms, Donna.”

I couldn’t swim, but I trusted him. I jumped. He caught me, again and again. Until the last time... when he didn’t.

I plunged into the cold water. It shocked me. I was terrified. But Dad quickly pulled me out, removed my wet clothes, wrapped me in his jacket, and took a photo. A picture that still says a thousand words.

Then he looked at me and said, “This is your first lesson, Donna. Never trust anyone. Not even your father.”

That moment could’ve felt like a betrayal. But it didn’t. I understood, on some instinctive level, that he was trying to protect me in the only way he knew how.

He didn’t want me to be anyone's victim.

As a surgeon my dad saved people in extraordinary ways. Yet he knew he was deeply flawed with selfish desires like every man. I believe he saved me from seeing men as all powerful. He raised me to question, be defiant, not see men as God.

Portrait of Donna age four © Dr. P.J. Ferrato 1953

HM: He sounds like a complex man. Let’s fast forward. Why do you think you documented domestic violence with such relentless passion?

DF: I was trained to find light in dark places.

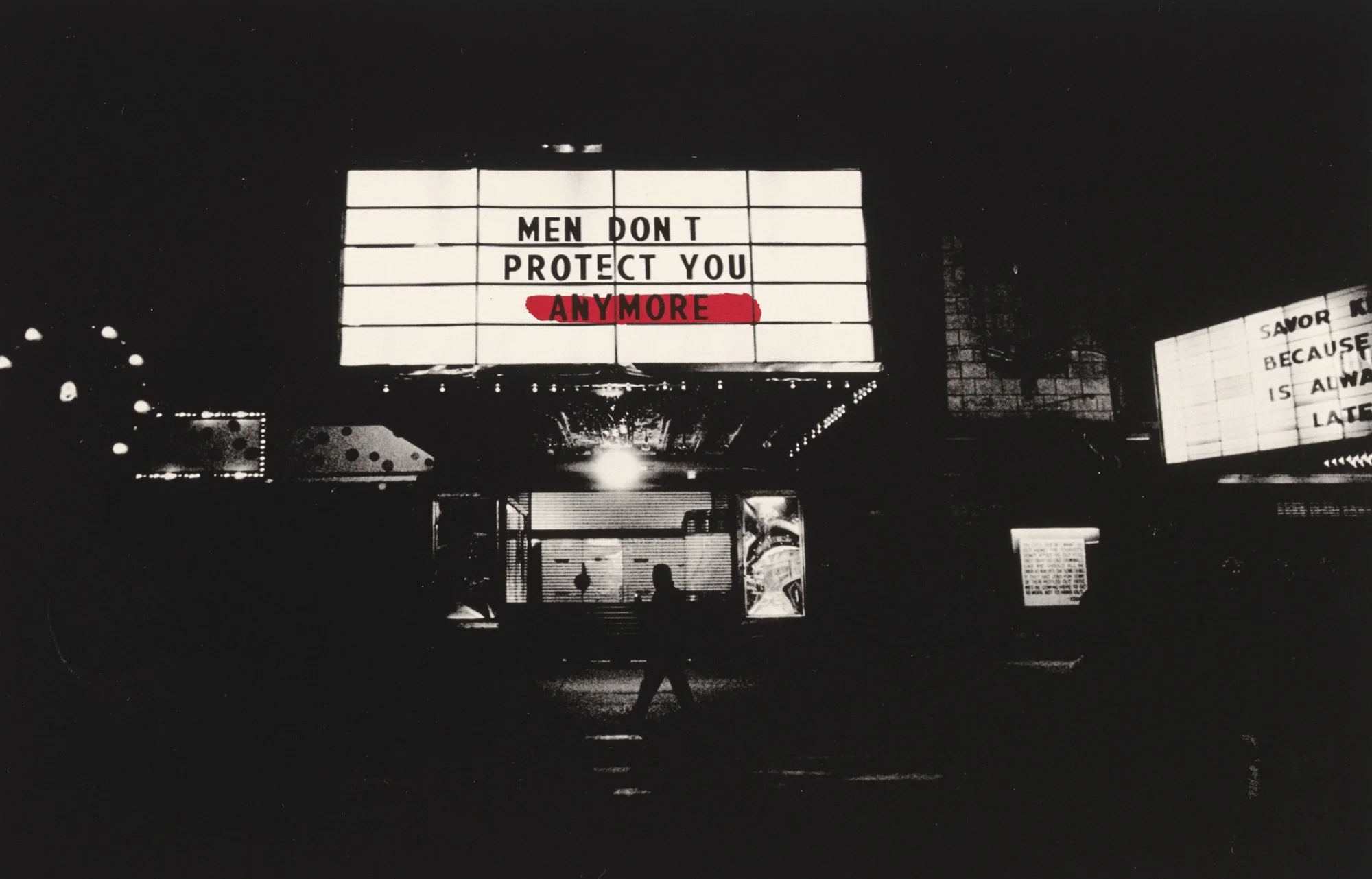

What I witnessed, again and again, was men getting away with violence, and threats of murder. Women were forced to run, to hide in shelters with their children, while the men stayed home.

I saw how the courts, the police, and even the neighbors, colluded with the bullies. Male violence was routinely swept under the rug. The message to women was unmistakable: put up. shut up, or die.

And while they stayed silent, they were dying, sometimes with orders of protection still in their pockets, bleeding out on their own front doorsteps.

It was the war on women that lit a fire in my belly.

Taking pictures wasn’t enough. I had to expose the truth: that society doesn’t just tolerate violence against women, it enables it. How? By blaming them. By shaming them. By rarely holding men accountable.

There was so much work to do back then.

And now, after four decades of fighting for rights and protections, we’re watching women, and their viable children, disappear through relentless attacks on abortion and reproduction rights. We have witnessed the rise of the all powerful fetus which has more rights than mothers and their viable children.

Women are the # 1 endangered species.

HM: Did you have help accessing shelters, survivors, courtrooms?

DF: I was the photographer, the reporter, the researcher. I wrote the letters, made the calls, conducted the interviews, and made sure every release form was signed.

I wasn’t completely alone—I had a dream team of one: my partner, the photographer Philip Jones Griffiths. In the early years, magazines wouldn’t take a chance on me, even when I had the photographs to prove I had something to say. The odds were against me because I was a woman.

I needed support, so I applied for the W. Eugene Smith Grant. I wanted the judges to understand what I intended to do with the help of this grant. Philip designed a magnificent dummy. It was so cool, and that's how I won the grant. With it came something called credibility which I needed more than the money.

Soon after, The Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday Magazine hired me to uncover the reality of domestic violence in the city of brotherly love. I wanted to go deeper into how the system worked. An assignment gave me access to a city and its inner workings. Dick Polman was the writer who was incredible to work with. We showed how technology and coordination created necessary lines of communication between the police, the courts, hospitals, hotlines, and battered women’s shelters. It was revolutionary.

HM: It was a different world. How did you navigate it as a woman with a camera?

DF: I was open and confident about why I was there. Mostly, I listened, and only photographed when women felt safe with a photographer in the house for months on end.

I wanted the women to understand my intentions. For instance, if I entered their house with the police, I was not with the police. I worked for magazines, which meant the photos might be published. I needed to be clear about who I was and why I was there. I also had to sign liability release forms with the police, with everyone, including the magazines. I did not try to protect myself from liability issues. Actually, I was more concerned with protecting everyone else so they didn't worry about me and I could work without restrictions.

I took risks because the mission mattered more than my life. I wanted to change the way people saw gender violence, not only as isolated incidents, but as a systemic failure. I wanted to challenge the immunity given to perpetrators and expose the limited, often tragic, options available to victims.

HM: You were documenting trauma. Did you ever stop and think, "Am I crazy?"

DF: Did I ever think I was crazy? No. Well… maybe yes.

I was way out on a limb.

I had a young child at home, being raised by her dad, my mom, and a rotation of kind, fun, young nannies. But I missed Fanny, my daughter constantly. She was always on my mind.

The truth is, I sacrificed our relationship and I loved her deeply, to keep doing this complicated, painful work that sometimes made no sense—except that it had to be done.

It was never about the money. In Philadelphia, I earned $3,000 for nine months of work—sleeping on floors and couches, living hand to mouth.

What compelled me wasn’t a paycheck. It was the urgency I felt to rattle the cage. That kept me going.

HM: What’s next for you?

DF: Right now, I just want to pick raspberries in Vermont before the season ends.

I’m participating in a group show on femicide at the Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery, and I’m hoping to try my hand at teaching at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. It feels like the right moment to begin passing something on.

I’m also focused on finding a permanent home for the Living with the Enemy archive. My dream institutions? The Library of Congress, the Angus & Betty McDougall Center for Photojournalism Studies at the Missouri School of Journalism, and John Jay College of Criminal Justice. That’s the wish list.

We want to find a concerned and visionary investor—someone who recognizes the historical importance of this archive, and who wants to help preserve it for future generations of journalists, activists, and students committed to justice and women’s rights.

HM: What advice would you give a young photographer—man or woman—wanting to take on risky, hard stories?

DF: Protect yourself. Stand up for women's survival. Take pictures or die.

HM: That's a heavy truth.

DF: Soon I will launch a series of workshops on the art of taking risky pictures.

For now, it's the will of independent female photographers like Smita Sharma, Kiana Hayeri, and Ximena Borrazas that gives me hope.

Smita Sharma works mainly in Pakistan. She documents the trafficking of underage girls in South Asia. Smita educates society by telling real stories from her book, "We Cry In Silence” as a TED Talk fellow.

Kiana Hayeri's book, “When Cages Fly” holds sway with real stories about Afghan women and girls whose rights ended after the Taliban took power. After the fall of Kabul, Hayeri returned to Afghanistan to document the lives of women and girls under control of gun-toting men.

Ximena Borrazas is a Spanish photographer with the tenacity and courage of a hummingbird. She is a photographer and a filmmaker, who produces work of magic as she endeavors to document sexual violence in conflict zones.

These women aren't just documenting the truth. They're changing it.

Independent women photographers are heroes in my mind. They do what they do for love.

HM: Donna, thank you. Your work continues to shape our understanding of justice, love, and survival.

DF: One day at a time. Thank you, dear Amnon! And most of all I appreciate your considerate, kind editor - Jasey is a saint.

love, Dr. Donna Ferrato

Leah O'Loughlin WA, DC. 2017. On a cold day, Leah walked with 2.6 million others to protest the "broke dick" presidency. © Donna Ferrato

Nahara, 14, is a warrior against abuse. Her will to survive was forged from growing up in a house of horror with her abusive father. In 2024, Nahara convinced the judge to grant a lifetime order of protection. She and her mom, Andrea, survived years of brutal coercive control . Self taught, Nahara is an honor roll student, and a member of the National Honor Society. Church St. NY © Donna Ferrato 2024

"Tribeca, my refuge and source of inspiration for 30 years, gives me strength to look for beauty even in dark times." Church Street. NY © Donna Ferrato 2024