Irina Werning: A Journey Through Stories, Cultures, and Photography

Irina Werning is a freelance photojournalist working on personal projects. She studied a BA in Economics and an MA in History in Buenos Aires and an MA in Photojournalism at Westminster University (2006). She won the Ian Parry Scholarship in 2006 (Sunday Times Magazine and Getty), BURN grant (Magnum Foundation) in 2012 and 1st place portrait Sony award in 2012. She was selected for the Joop Swart Masterclass, World Press Photo 2007. She was chosen by Time Magazine as one of the nine Argentinian photographers you need to follow (2015) and her Back to the Future Book was chosen by Time Magazine as one of the best photo-books of 2014. In 2020 she was awarded the Emergency Covid Grant (National Geographic) and a Pulitzer Reporting Grant (2021). She is the winner of the World Press Photo award for Story category in 2022. She is the recipient of the Eugene Smith Grant 2023 and the Leica International Women’s Grant 2025.

HM: Could you tell us a little bit about where you grew up, what your childhood was like, and how—by chance or by design—you eventually found your way into photography?

IW: I’m from Buenos Aires, where I grew up and spent most of my early life. My first studies were very different from what I do today—I did a BA in Economics, and later, an MA in History.

After finishing my studies, I traveled for many years as a backpacker. I spent almost two years in India, moving from place to place, and then later, I spent a year and a half living in Israel.

After that, I felt it was time to keep moving. I went to Europe and landed in London, but when I arrived, I didn’t really know what to do with my life.

HM: Was that a difficult period for you?

IW: I always had this feeling that I was meant to do something meaningful to me but I didn’t know what that was.

Some never find that thing, and I wasn’t sure if I ever would. So I was in London, working as a sociologist, trying to find my path, but I was deeply unsettled.

FINDING PHOTOGRAPHY AT 30

HM: So how did photography enter your life?

IW: It happened almost by accident. When I was 30, I read an interview in a magazine with Colin Jacobson, a legendary photo editor here in London. He was describing the life of a photojournalist—chasing stories, being out in the world, documenting reality.

As I read his words, I realized This is what I want to do.

Looking back, I understood that I had always been chasing stories, even as a backpacker and while studying history. It was always about stories for me.

So, impulsively, I wrote him an email. I said, “I want to meet you.” To my surprise, he replied and invited me to meet him. At that time, he was directing an MA program in photojournalism at Westminster University. He said, “I love your background—why don’t you apply?”

HM: That must have been an exciting moment.

IW: It was the turning point.

I had never picked up a camera in my life. I went into this photojournalism program at 30 years old, surrounded by people who had been taking pictures since they were kids. Around me I heard “I got my first camera when I was 11,” and there I was—completely clueless.

I had to learn the craft from scratch. And photography takes a long time to learn. There’s no shortcut. You have to go out, make mistakes, and keep trying. It’s trial and error until you find your style.

THE EARLY STRUGGLES

HM: What were those first years like as you were learning and starting to work in the field?

IW: Hard. London is full of talented photographers, and breaking through felt almost impossible. To survive, I worked as a nanny from 9 to 5 during the week—for almost four years.

Then, on evenings and weekends, I would work on my photography projects. It was exhausting, but I was determined to keep going.

Eventually, I went back to Argentina, where I tried to survive as a photographer.

THE BREAKTHROUGH: BACK TO THE FUTURE

HM: Tell me about Back to the Future, the project that brought you wider recognition.

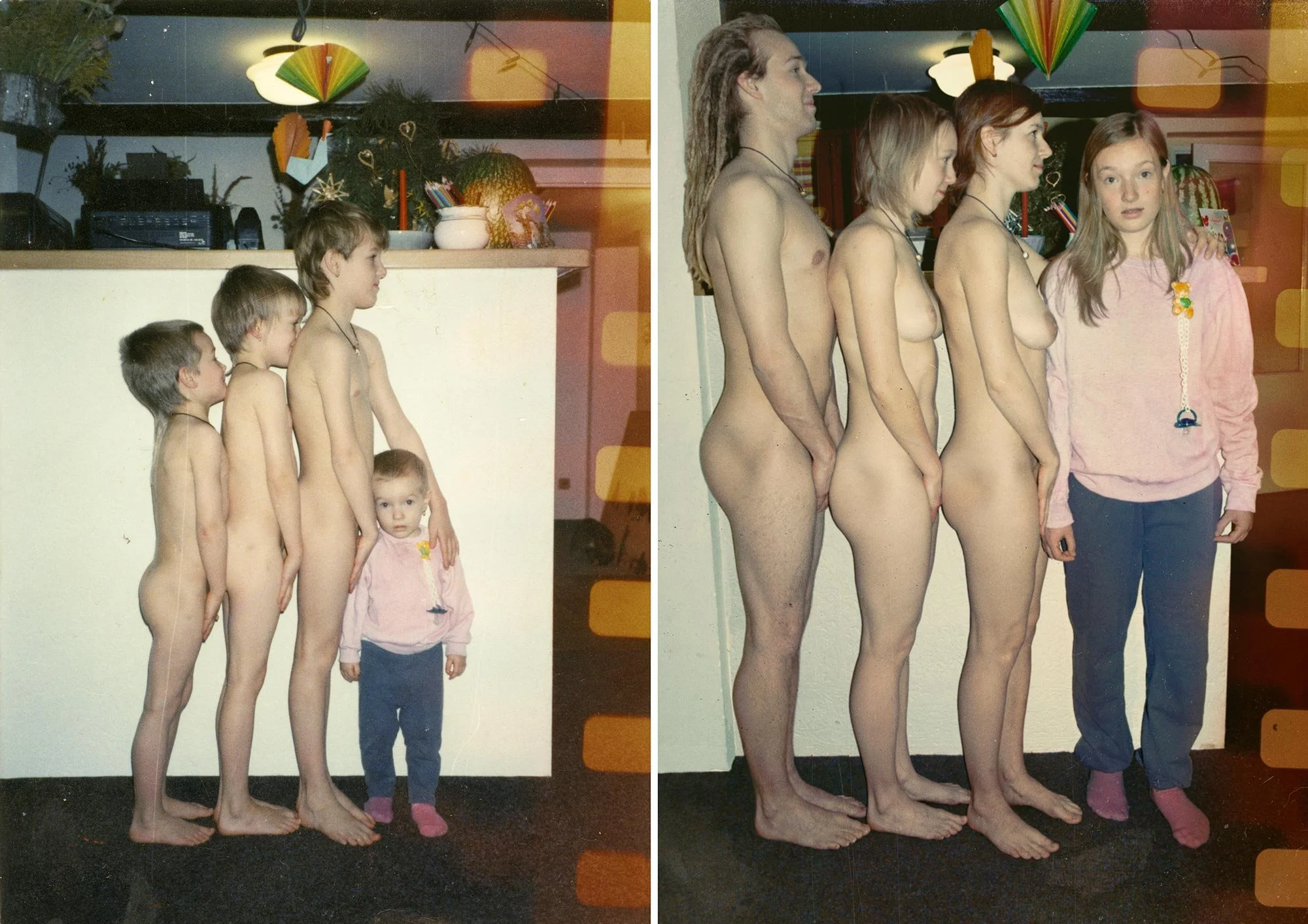

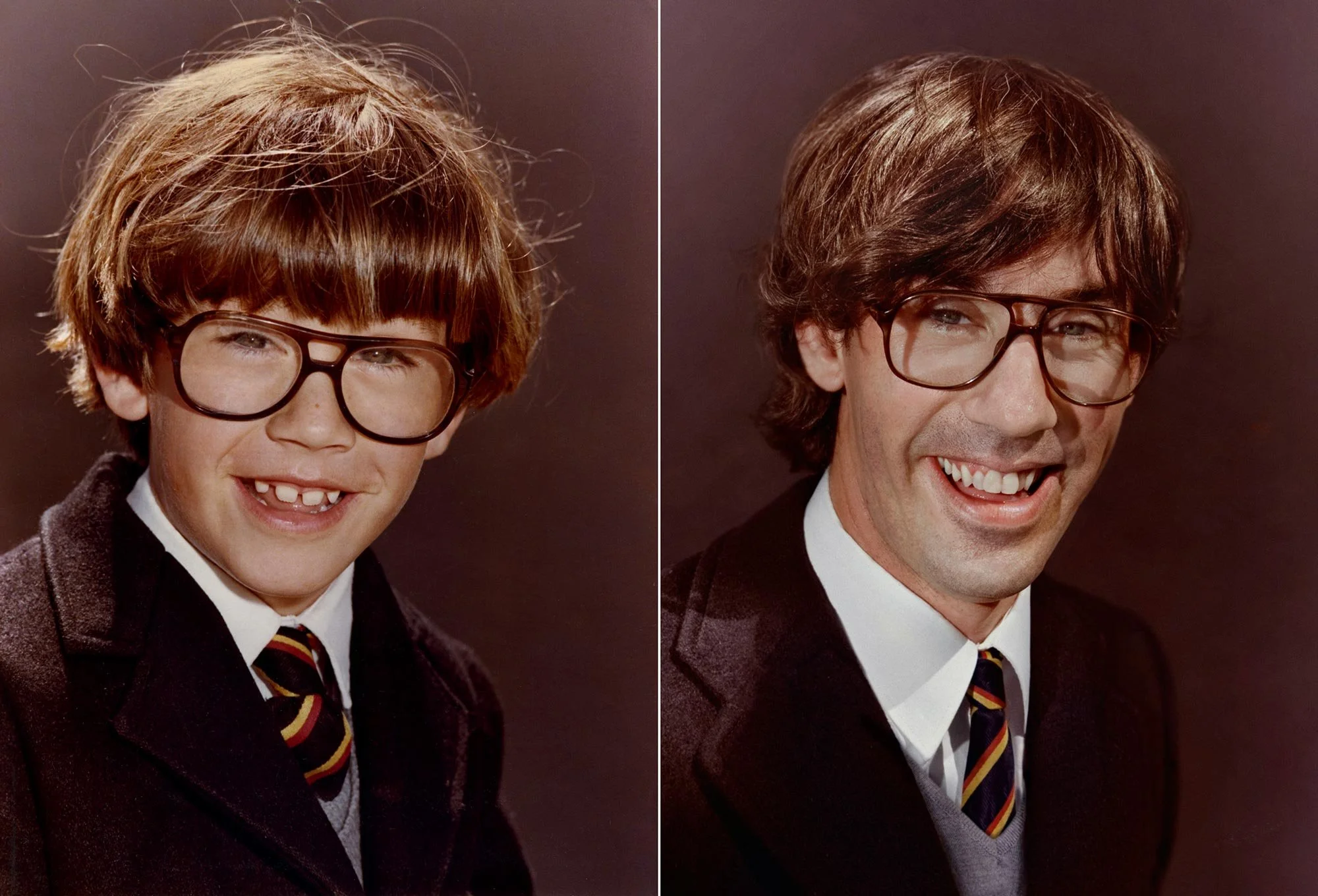

IW: The project went viral and became the biggest adventure: six years, in 49 countries. I met so many people, each picture was a whole new world I entered. I learnt so much about lighting, sewing and the human body as we age.

THE LONG HAIR PROJECT - 18 YEARS IN THE MAKING

HM: The project you’ve just finished sounds incredibly unique—a visual exploration of women with long hair in Argentina. Can you tell me how it began?

IW: This project started very differently from my others. Most of my work begins with an idea, then I research it, develop it, and plan carefully. But this one was purely intuitive—it came straight from my gut.

Back in 2006, the first year I began photography, I received a grant called the Ian Parry Award. With that money, I returned to Argentina to work on a project about rural schools in remote mountain areas.

While traveling, I started noticing women with extremely long hair. In many indigenous cultures—including in Latin America, North America, and even among the Sikh people—hair holds deep symbolic meaning. It’s believed to be an extension of the mind or spirit.

In South America, the waves of immigration mixed with the indigenous communities creating a hybrid and rich population. Because of this, many ancestral traditions are part of our culture, even if we are not aware.

I began photographing these women quietly. At first, I didn’t think of it as a project. It was just something that fascinated me.

HM: So how did it grow into a full project over 18 years?

IW: I continued traveling and searching for these women, putting up signs in towns and organizing long hair competitions to find these women. Over time, it became clear that there was something much deeper here.

At first, I photographed them from behind, focusing only on the hair. Later, I began including faces, trying to avoid visual repetition.

It became an anthropological project, —a way to explore the mixed identity of Latin America, to understand where we come from and who we are.

GLOBALIZATION AND PRESERVATION

HM: After so many years, what did you discover when you went back recently to the same communities?

IW: I went back expecting to find that globalization had erased these traditions. As photographers, we often assume we are documenting something that’s disappearing.

But to my surprise, it was thriving. Yes, mobile phones and global culture had reached even these remote villages, but the tradition of long hair was still very alive.

It was incredibly moving to see these women come together, to hear their stories, and to realize that it was more alive than ever.

AWARDS AND RECOGNITION

HM: And the project received major recognition, didn’t it?

IW: Yes, one of the stories from this project won the World Press Photo Award in 2022, and I also received the Eugene Smith Grant in 2023.

The project was so personal and long-term.

ADVICE FOR YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHERS

HM: You’ve been photographing for almost 20 years now. What advice would you give to young photographers just starting out?

IW: Two things.

Photography is very difficult—like anything you want to do well. It requires total dedication. If you don’t feel that passion, it will be too hard to sustain.

Second, for the first seven years, don’t rely on photography to pay your bills. Get another job. Take the pressure off.

It takes at least seven years to really find your style, to grow your skills, and to start earning a living from it. So support yourself another way, and use your free time to create projects.

And don’t just study photography. Study other subjects—history, science, literature—because they will make your work richer and help you think in different ways.

ON AI AND THE FUTURE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

HM: What do you think about AI and all the changes happening in photography right now?

IW: I don’t see AI as a threat to my work. I don’t use it—I don’t even know how to use Photoshop!

My work is about reality. It’s about connecting deeply with people and places. There will always be a demand for real, authentic stories.

I think there will need to be systems to verify the authenticity of images—like encrypted files or traceable raw formats—but for documentary photography, AI cannot replace the human connection.

LOOKING AHEAD

HM: What’s next for you?

IW: I’m currently working on a project about the relationship between humans and animals. It has many layers.

For example, here in London, I’ve been photographing dog screenings —there are 18 of these cinemas, and every Sunday I go and document them.

This project explores our relationships with animals in different ways—sometimes tender, sometimes strange. It also touches on the food industry and how humans use animals in so many aspects of life.

It’s still evolving as it goes.

FINAL REFLECTIONS

HM: When you look back over your journey, from Buenos Aires to London to the far corners of Argentina, what do you feel?

IW: Grateful. My life has been full of unexpected turns.

Photography gave me a way to make sense of my experiences, to connect with others, and to tell stories.

I know I will always keep working on projects. They come to me like ideas that won’t let go. I have many ideas and never enough time or resources, but that’s part of the challenge—and the joy.

All images © Irina Werning unless stated otherwise