Stephen Shames: Documenting Revolution, Conflict, and Change through the Lens

Stephen Shames creates award winning photo essays on social issues for foundations, advocacy organizations, the media, and museums. He is the author of 15 photo books. His latest is Stephen Shames: a lifetime in photography (Kehrer Verlag). His photographs are in the permanent collections of 42 museums. Steve is represented by the Amar Gallery in London and Steven Kasher Gallery in New York.

© Heidi Gutman

I. ORIGINS AND EARLY INFLUENCES

HM: So, probably the best place to start is at the very beginning. Where did you grow up?

SS: I grew up in many places, but I was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts — and made the papers on my first day. Both Boston dailies ran a photo of me as the first “Harvard GI baby.” My dad had just returned from WWII to study law at Harvard, and my mom, then editor of the Radcliffe paper, turned down a New York Times job to raise a family — typical of the late 1940s.

Still, she remained a creative force. She collected art passionately, buying directly from Japanese artists long before it was common. Our home was filled with what I thought was ordinary furniture — Saarinen tables, early American design classics, even a Sam Maloof rocking chair like JFK’s. Only later did I realize I’d grown up surrounded by future museum pieces.

HM: It sounds like you grew up in a pretty unusual environment.

SS: Absolutely. My childhood wasn’t what you’d call typical suburban middle class.

We moved to Chicago when I was about a year old, and eventually, my parents built a house in the suburbs. My mom designed it herself, which was radical for the time. In the 1950s, nobody had open-concept spaces, but our house had an open kitchen and living room, with the entire south-facing wall made of sliding glass doors.

In the winter, sunlight poured in and heated the whole room naturally — a kind of early eco-design before that was even a thing. She also left half the property covered with trees, refusing to cut them down even when the neighbors thought she was crazy. Everyone else wanted perfectly trimmed lawns, but my mom insisted on this balance between architecture and nature.

She even created a Japanese-inspired garden by the entrance, complete with a massive boulder and carefully curated plants. At the time, I just thought this was normal life. But looking back, I realize how much that aesthetic sensibility shaped me.

1976 - Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Teenage girls at Kits Beach.

HM: So, your mom clearly had a big influence on your artistic eye. What about your dad?

SS: My dad was very different — more traditional, more pragmatic. He worked in law and politics. At one point, he was actually offered a sub-cabinet position by President John F. Kennedy — Deputy Secretary of the Navy — but he turned it down. It would’ve meant a huge pay cut, and financial security was very important to my parents.

He was also deeply involved in Chicago politics. He worked closely with Mayor Richard J. Daley, who was famous — or infamous — for his machine politics. My dad would tell these incredible stories about the backroom deals and the sheer chaos behind the scenes. That exposure to politics gave me an early fascination with power, society, and how systems work.

HM: It sounds like your parents’ worlds — art and politics — gave you a very rich foundation.

SS: Exactly. But like many families, ours was also… complicated. Dysfunctional, even.

Over the years, I’ve come to believe that half of humanity grows up in some form of dysfunction. The difference is how you deal with it. Some people just stay angry and pass that pain on to others. Others, like many artists and photographers I know, take that turmoil and transform it into something meaningful.

I think that’s what I did. My way of processing pain and confusion was to turn it into images, into storytelling. That’s why I connect so deeply with the people I photograph — there’s this unspoken emotional understanding.

When you walk into a room with someone whose life has been shaped by hardship, they know immediately — without words — whether you truly get it. Whether you’re one of them, or just a tourist passing through their world. That level of connection has been essential to my work as a photojournalist.

1985 - Ventura, California, USA

Homeless, 11-year-old Kevin sleeps in the front seat of the family car. His 13-year-old brother, Christopher, sleeps in the back. The Wallace family has been homeless for two years. They live at McGrath State Park on the beach. Families are allowed to camp for 14 days and then must leave for 24 hours. “This has not been an easy life on the kids,” says their mom, “The other kids call them hobos.”

II. EDUCATION AND POLITICAL AWAKENING

HM: Where did you go to school?

SS: I went to a very unusual high school called the Putney School in Vermont. It was a progressive, arts-focused boarding school with a farm on campus. Students worked on the farm as part of their education — milking cows, mucking stalls, planting crops.

There were no uniforms, no chapel, none of the traditional boarding-school trappings. It was founded by Carmelita Hinton, a wealthy idealist who was radical for her time. Her vision was to create an environment where students could explore creativity, responsibility, and community. The school attracted the children of artists, intellectuals, and activists. Some of my classmates went on to become incredibly successful — the filmmaker Errol Morris was in my class, as was writer Lydia Davis.

We had small seminar-style classes, which prepared me well for college. When I got to Berkeley, I realized I’d already read most of the literature the professors were assigning.

I was a bit of a nerd — though athletic too. As a kid, I was deeply interested in politics and history. I remember devouring Arthur Schlesinger’s books The Age of Roosevelt and The Age of Jackson when I was just twelve or thirteen.

HM: So you had this unique upbringing — a mix of art, politics, and progressive education. How did all of that lead you to photography?

SS: Honestly, it wasn’t a straight path. Photography came to me gradually, through this combination of influences — my mother’s artistic eye, my father’s fascination with power and politics, and my own search for a way to make sense of everything I was feeling.

Photography became my way of engaging with the world. It was a tool for storytelling, for bearing witness, for finding beauty in chaos. And maybe, deep down, it was also a way of healing myself by turning difficult emotions into something that could speak to others.

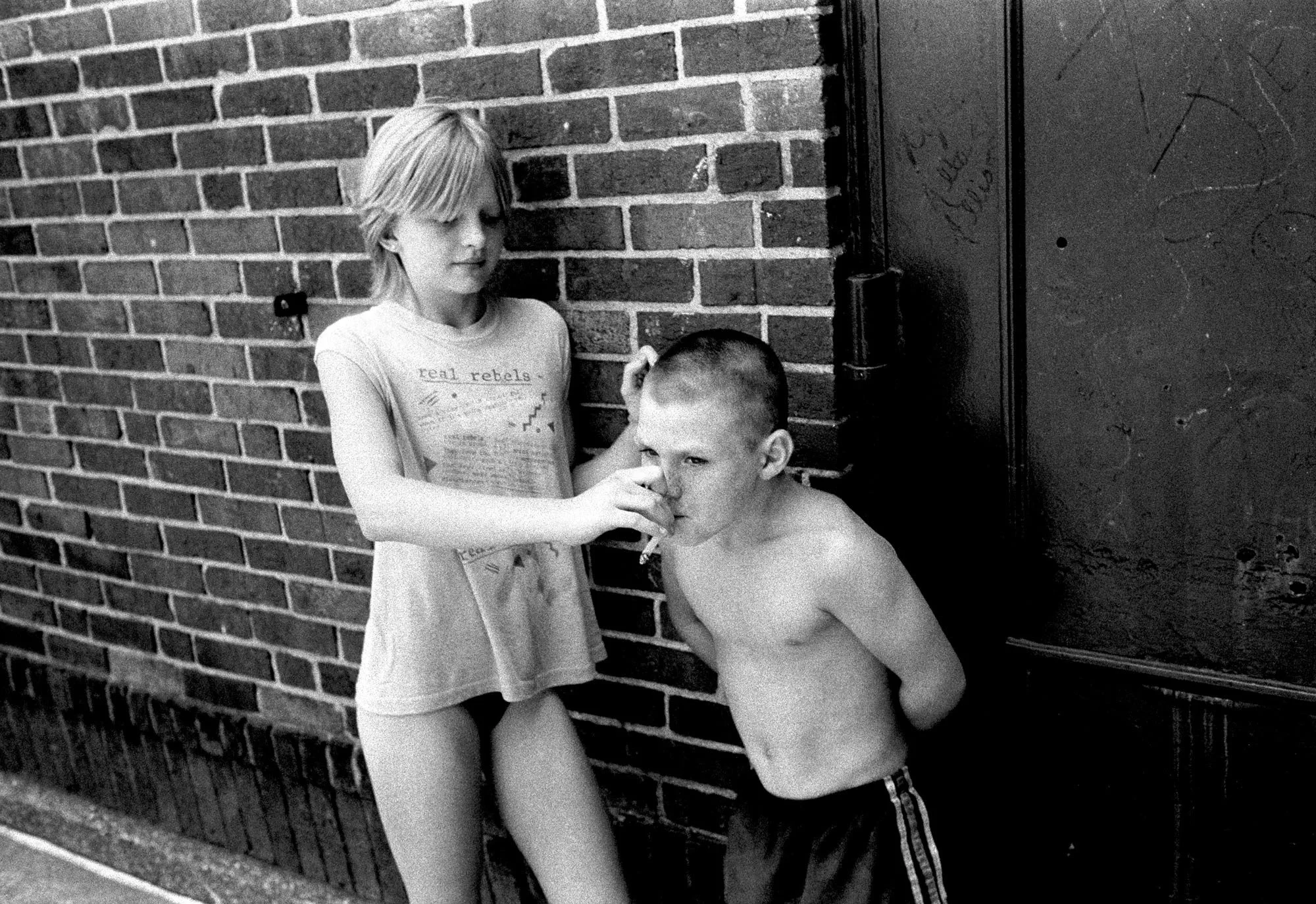

1985 - Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Girl gives younger boy a cigarette in Lower Price Hill, a neighborhood of poor whites from Kentucky and West Virginia.

III. DISCOVERY OF PHOTOGRAPHY AND BERKELEY YEARS

HM: So, how did you first get into photography?

SS: You know, it’s kind of funny — at Putney, they had a really good photography program, but I never took a single class. I was more focused on history and reading.

When I got to Berkeley, I continued that pattern. Summers were always about working. My dad believed kids should have jobs — and that stuck with me. In the summer of 1966, I worked in a plastics factory. It was gritty, monotonous work.

By August, I’d had enough, so I quit and hitchhiked to New York City. One day, out of boredom, I wandered into a pawn shop and bought a cheap little camera — maybe fifty bucks. I started walking around, taking pictures, and something just clicked. That was the beginning.

HM: So it wasn’t a planned thing at all — just completely spontaneous?

SS: Totally spontaneous. It was like the camera found me.

When I got back to Berkeley, I kept shooting. One of the first significant photographs I ever took was of Martin Luther King Jr. It was maybe my fifteenth or twentieth roll of film — I was still completely new to it.

King was speaking at Sproul Hall. The place was packed. Through a bit of luck — and my knack for talking my way into places I probably shouldn’t be — I walked out of Sproul Hall with him and sat right at his feet during the speech.

If you look up Martin Luther King UC Berkeley 1967, there’s a shot of him speaking — and right in front, a skinny kid wearing sunglasses. That’s me.

September 15 - 19, 1969- San Francisco, California, USA

Police arrest Marc Norton, a student at UC Santa Cruz at a protest organized by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) at the International Industrialists Conference (IIC). IIC attendees include Nelson Rockefeller, Henry Kissinger, Kaiser, Union Carbide, Standard Oil, IBM, Bank of America. US Steel, Wells Fargo, Royal Dutch Petroleum, Philips, Unilever, Siemens, FIAT, Mitsui, and Mitsubishi.

HM: That’s an incredible story — and such a different time. What was Berkeley like back then?

SS: Oh, it was electric — a total hub of activism.

When I arrived, it was the year after the Free Speech Movement, so the radical energy was still alive. Protests against the Vietnam War were constant. One of my roommates, Marty Roysher, had been on the steering committee of the Free Speech Movement.

At first, I was more of a participant than a photographer. I served as a monitor at Vietnam marches, ran for student senate, and got caught up in the politics. Eventually, I realized politics wasn’t for me — I wanted to be the artist of the revolution.

HM: And that’s when you started really photographing protests?

SS: Exactly. I started documenting demonstrations — not just the events, but the police brutality. The cops would come on campus, beating students, arresting peaceful protesters.

In 1967 — the “Summer of Love” — everything was wild. Runaway teenagers flooded into Haight-Ashbury and Telegraph Avenue. The police began rounding them up, and that’s when I got my first big break.

Max Scheer, the editor of the Berkeley Barb, spotted me and said, “Hey kid, you want to shoot for us?” I had no credentials, no experience, but he ran my first photos. That’s how my career began.

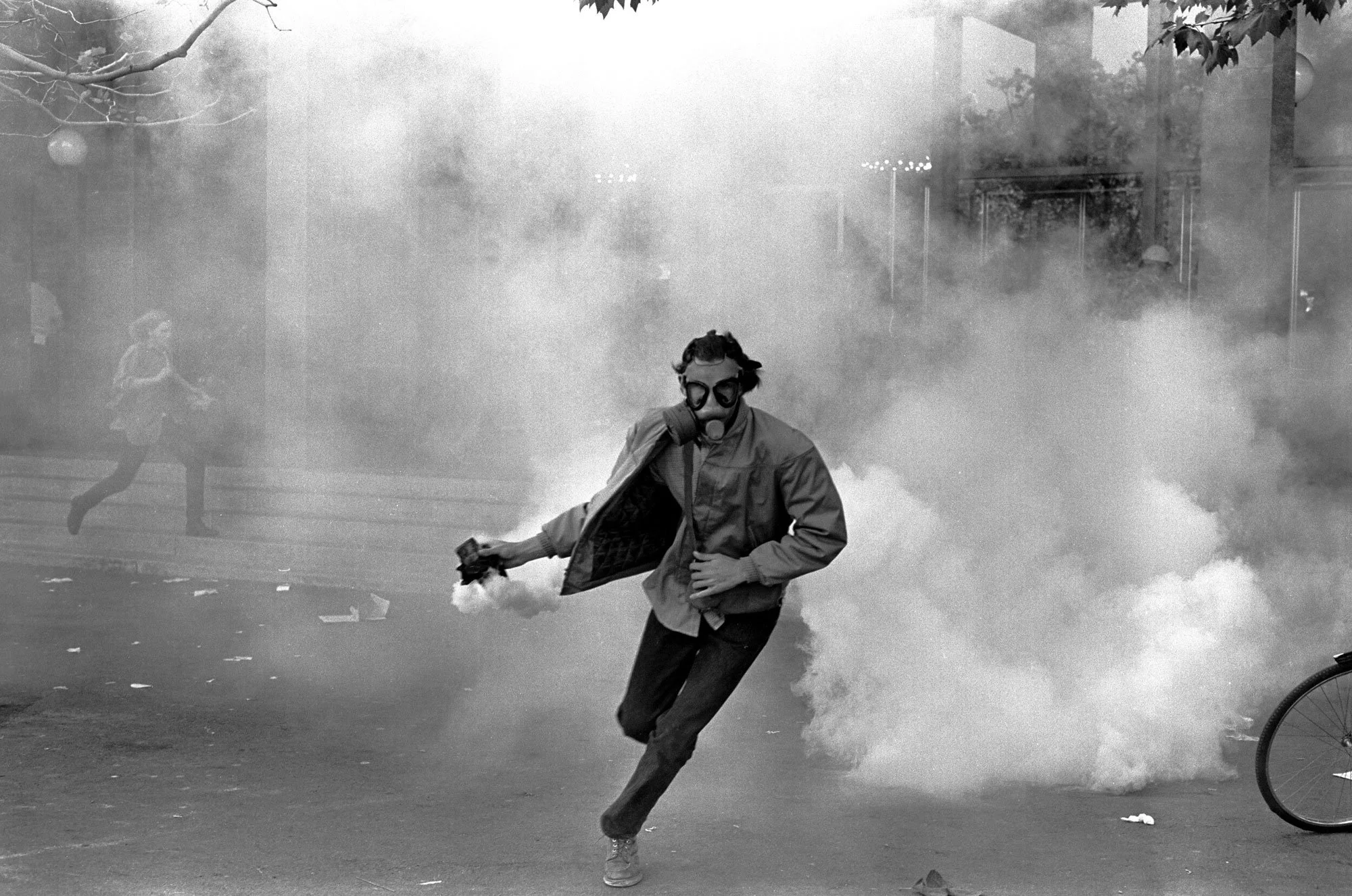

May 5, 1970 - Berkeley, California, USA

Protester wearing gas mask throws tear gas back at the police during protest at the University of California at Berkeley against the Cambodian Incursion of the War in Vietnam.

IV. THE BLACK PANTHERS AND THE MEDIA REVOLUTION

HM: And somewhere in there, you connected with the Black Panthers. How did that come about?

SS: April 15, 1967 — I’ll never forget the date. My dad came up for the first big anti-war march in San Francisco. I saw Bobby Seale and Huey Newton for the first time — they were total unknowns then, just a few guys selling Mao’s Little Red Book to raise money.

They caught my eye because they were so charismatic. I took one frame. They were on the Berkeley campus a lot and I also photographed them there. I took my photos to their office in Berkeley, Bobby liked my photos. That’s how our relationship began.

From there, Bobby took me under his wing. I had incredible access — inside homes, schools, offices. When George Jackson was killed in prison, I was the only photographer allowed inside the church for the funeral. All the others had to stay outside. That trust was everything.

1968 - Oakland, California, USA

Panthers stand just off stage at a Free Huey rally in DeFremery Park. Cle Brooks (arms folded) was a San Francisco Panther who went to San Quentin Prison and started the San Quentin chapter of the Black Panther Party.

HM: Were you also publishing those photos elsewhere?

SS: Yes, the Panthers wanted their story out there. They encouraged me to sell the images to national publications. My first big break was a Newsweek cover story on the Panthers.

I’d mostly been shooting black-and-white, but Newsweek wanted color. I brought Alan Copeland with me, and we shot it together. That cover helped launch my career as a serious photojournalist.

May 1, 1970 - New Haven, Connecticut, USA

Boy gives raised fist salute as he and a friend sit on a statue in front of the New Haven County Courthouse during a demonstration of 15,000 people during the Bobby Seale / Ericka Huggins trial. Bobby Seale, Chairman of the Black Panther Party is on trial along with Ericka Huggins for murder. Both are acquitted.

HM: The Panthers were known for their politics but also their image. How did they use the media?

SS: They were media geniuses. Huey and Bobby understood the power of visuals — the black beret, the leather jacket, the blue shirt. They looked organized, defiant, disciplined.

And unlike many movements, they had real structure. Most of the branches were run by women — about sixty percent of the organization’s leadership.

But what really threatened the government wasn’t their guns — it was their programs: free breakfasts, community clinics, and education. Hoover called the Breakfast Program “the single greatest threat to the internal security of the United States.” Think about that — not the weapons, but feeding children.

1971 - Oakland, California, USA

Black Panther children in a classroom at the Intercommunal Youth Institute, the Black Panther school.

V. FROM REVOLUTION TO WAR: EXPANDING THE LENS

HM: When did you personally transition into photography full-time?

SS: By 1968, I realized this was my calling. I freelanced for Newsweek, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Liberation News Service.

By 1976, I moved to New York and joined Black Star, the top photo agency of the time. They represented incredible photographers like Jim Nachtwey and Christopher Morris. It was the place to be.

HM: You went on to cover conflicts internationally. Tell us about Northern Ireland.

SS: In the early ’70s, Rolling Stone sent me to cover Northern Ireland. It was intense — constant tension. One night, in a bar, a man asked me, “Are you Catholic or Protestant?” I said, “I’m Jewish.” He replied, “Yeah, but are you a Catholic Jew or a Protestant Jew?” (Laughs.)

That summed up the absurdity of sectarian conflict. I photographed IRA fighters, teenagers with guns, and people living under siege. The stakes were life and death — but people were still human, still laughing.

1971 - Belfast; Northern Ireland

Four boys in a Catholic neighborhood pose with syringes found on the ground.

HM: You also covered Lebanon during its civil war. What was that like?

SS: Lebanon was chaos. The airport was closed, so I had to arrive by boat from Cyprus. Each faction required its own press pass — Phalangists, Druze, Palestinians.

Checkpoints were manned by teenagers with automatic weapons. That was the scariest part — they were unpredictable. I remember photographing child soldiers, kids as young as eleven, riding bicycles with M16s slung over their shoulders.

In war zones, survival depends on earning trust fast. You find the local leader — if they trust you, you’re safe. If not, you’re in real trouble.

HM: How do you feel about the press today compared to back then?

SS: It’s changed dramatically. Back then, even if you disagreed with an outlet, you trusted they were trying to tell the truth. There was one shared set of facts.

Today, it’s fragmented — propaganda, algorithms, echo chambers. In conflict zones, people sometimes assume you’re a spy. The erosion of trust makes journalism harder and more dangerous.

September 12, 2001 - New York, New York, USA

Putting the flag up at Ground Zero.

VI. PROJECTS OF MEANING: FROM ADOLESCENCE TO POVERTY

HM: You once mentioned an early project about teenagers, though it was never published as a book. Can you tell me about it?

SS: Yes. It was called Puberty Rites. The idea was to explore adolescence — that transformation from childhood to adulthood. I saw modern teenage behavior as a kind of ritual, just like the structured initiations in so-called “primitive societies.”

In traditional cultures, those rites are guided and celebrated. In ours, kids are left to figure it out alone — through partying, romance, rebellion. It’s all ritual, just unacknowledged.

1985 - Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Teenager jumps his bike over friends in Lower Price Hill, a community of southern whites.

HM: How did you begin photographing those teenagers?

SS: It happened by accident. I was living at Waterside Plaza in New York when a group of kids were making noise in the hallway. I was about to tell them off — then realized, these are my subjects.

I met their parents, got release forms, and set clear rules. The kids weren’t destructive, just curious and experimental. Watching them navigate those emotions felt like witnessing a universal human rite.

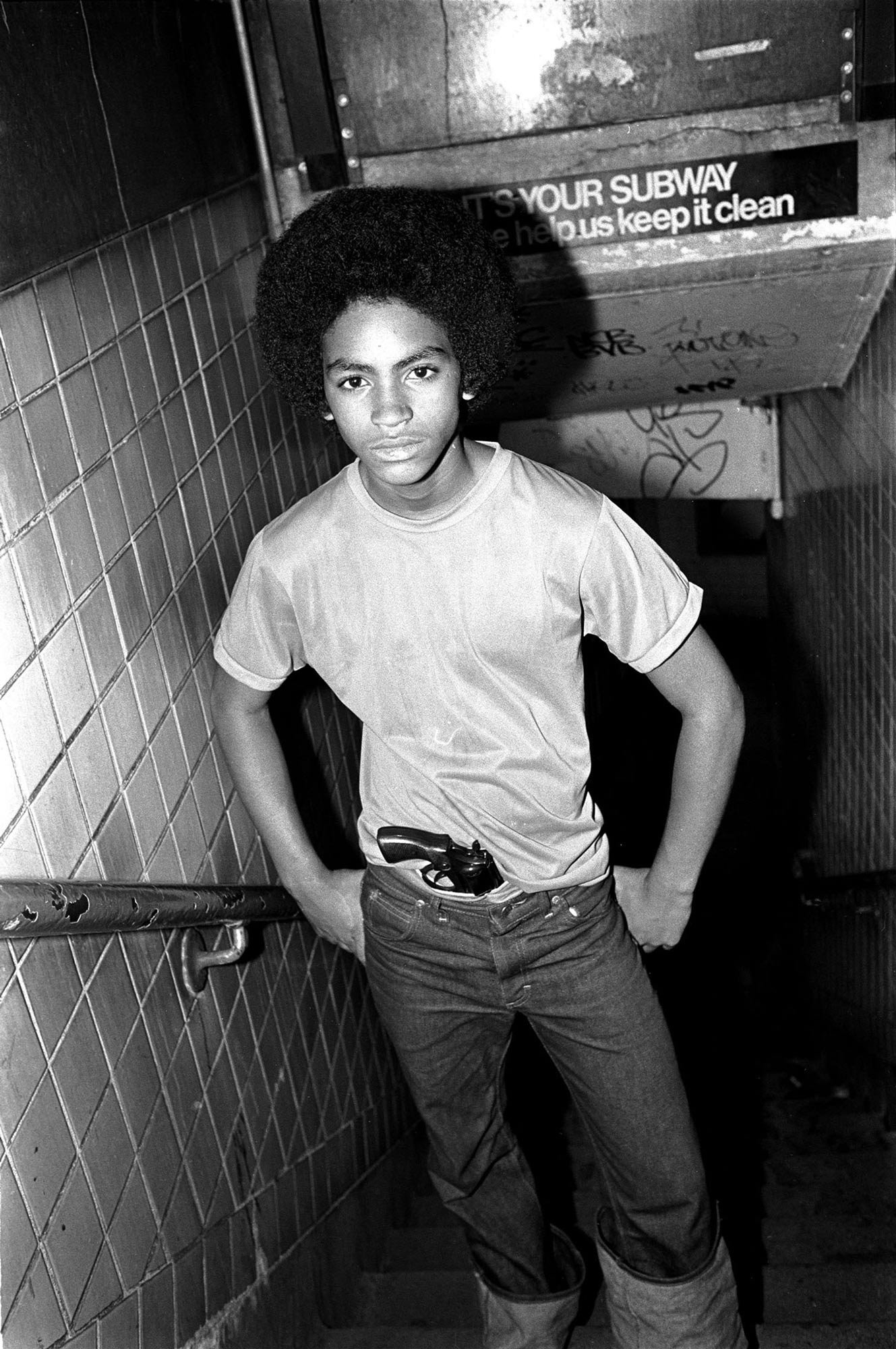

1980 - New York, New York, USA

15-year-old who hustles in Times Square emerges from the subway with a gun.

HM: Can you describe how you embedded yourself within the communities you were photographing?

SS: Living with people is essential. Life doesn’t happen on a schedule — you have to be there for the moments that matter.

When I was photographing a steelworker family, I stayed on their sofa. One night, the father broke down and I drove him to the hospital. That kind of intimacy shows the emotional truth behind statistics.

When I documented homeless families in Ventura County, I camped with them on the beach. People can tell when you’re really living alongside them — that’s when trust, and honesty, appear in the photos.

HM: Did you find that many experts on poverty lacked that kind of direct experience?

SS: Absolutely. I once met with an advisory committee of leading academics studying poverty. None of them had ever stayed overnight in the homes of the people they wrote about.

That disconnect stunned me. The people being studied always know when outsiders are parachuting in. You can’t understand lives you haven’t lived alongside.

1984 - Anaheim, Orange County, California, USA:

Jack Ruelas' friend points a cocked gun he takes to school to "protect myself from the gangs" at him, The friend said the gun was not loaded. Jack is the son of Mexican immigrants who work three jobs at Disneyland motels so he and his siblings could get a good education and have a better life. Jack is in a gang.

Outside the Dream put faces on the 13 million poor children living in poverty — adrift in the richest nation in history. In the 1980s children constitute one half of all poor people in America. Today, as income inequality grows, poverty —especially child poverty — is again an issue.

HM: That seems to be a thread running through all your work — a deep, human connection to your subjects.

SS: Exactly. Whether I’m photographing teenagers creating their own rituals or families struggling with poverty, I try to reveal the underlying humanity.

Photography is about cutting through abstraction and showing real lives — messy, complicated, and profoundly meaningful.

Summer, 1995 - Costa Mesa, California, USA

Girls read and talk at Girls Inc’s summer camp. Girls Incorporated helps girls ages 9 to 18 avoid early sexual activity and pregnancy. National assessment showed a 50% drop in pregnancy rate and a significant delay in initiation of intercourse among young teens.

Pursuing the Dream is a series of photographs about community people helping their neighbors. These community programs help parents do a better job by teaching them skills, providing support, and involving the whole community in raising children.

VII. REFLECTION AND LEGACY

HM: Looking back, what stands out most from all these experiences?

SS: Two things.

First, the courage and brilliance of the people I covered — Panthers in Oakland, activists in Belfast, kids in Lebanon’s war.

Second, the power of images. A single photograph can tell the truth, challenge authority, even change history. That’s what kept me going — even when it was dangerous.

Photography isn’t just about witnessing events. It’s about making sure the world can’t look away.

All images © Stephen Shames unless stated otherwise

To purchase a copy of Stephen’s new book Stephen Shames: a lifetime in photography click on a link below

Europe: Stephen Shames - Kehrer Verlag

US: www.ebay.com