“It Was Survival, Then it Became a Language”: Daro Sulakauri on Photography

Daro Sulakauri is a photojournalist and visual artist whose work captures the complex social and political realities of the Caucasus region. A graduate of the International Center of Photography in New York, where she studied on the John & Marie Phillips Scholarship and the ICP Director’s Fund, she gained early recognition for her documentation of Chechen refugees in Georgia’s Pankisi Gorge, earning the Young Photographers in the Caucasus Award from Magnum Photos.

Her stories focus on taboo and underreported social and human rights issues, including the lives of mineworkers, ethnic minorities, Georgia’s ongoing stolen babies investigation, which has documented illegal adoption schemes, and early marriages in Georgia, which brought the issue into public consciousness and contributed to legal reform, raising the country’s legal marriage age.

She was named one of LensCulture’s “21 Great Female Photographers”, listed among PDN’s 30 Emerging Photographers to Watch, selected for 30 Under 30 Women Photographers, and received first prize for the Human Rights House Foundation in London. She is also an alumna of the World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass.

Her work appears in The New York Times, Reuters, National Geographic, Stern Crime among others. She has earned the Reuters Photojournalism Grant, and became a Canon Ambassador. In 2022 became a Catchlight Global Fellow. She has also received the LensCulture Visual Storytelling Award, EU Prize for Journalism, François Demulder Grant and was on the team for Hansel Mieth Prize (Zeit Magazine, 2023). In 2024, she became the first Georgian TED Fellow, joining a global network of changemakers.

Sulakauri is the screenwriter and protagonist of the documentary film ‘Double Aliens' , directed by Ugis Olte. She is the creator of shifting-borders.com, a trilingual multimedia platform documenting life along South Ossetia’s occupation line, and the author of two hand-made books exploring pandemic and rave culture.

Beyond photography, Daro is a two-time Georgian Championship gold medalist and Tbilisi State Champion in pistol shooting, who previously represented Georgia at World Cups and European Cups.

CHILDHOOD IN COLLAPSE

HM: Daro, you’ve said that growing up in Georgia in the 1990s shaped everything about how you see the world. Can you tell me about that time?

DS: I’m part of the 90s generation. I grew up during the collapse and immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union, when Georgia was going through total chaos and transition. It was a very violent, unstable time.

We often had no electricity, no water, no heating. My family home is in the center of Tbilisi, so everything happened right in front of us — the civil war, protests, the Rose Revolution later on. Political life was not abstract; it was literally parallel to our everyday life.

At one point it became so dangerous that my parents moved us to my grandparents’ house, because it wasn’t safe to walk from one room to another. Gunshots were constant. You could hear them all the time.

And yet, there were moments of joy. When the electricity suddenly came on, even for five minutes, everyone would shout, “Oh!” and laugh, and then — darkness again. Sometimes guests would show up, and there’d be drinking and laughter in the middle of complete uncertainty. Only looking back I realize how much transition we went through as a society — the blackouts, the shortages, the fear, and then slowly, the first signs of hope as the country tried to rebuild.

Living through that, right at street level, definitely shaped how I see the world.

LEAVING – AND RETURNING – TO GEORGIA

HM: And then your family moved to the United States. How old were you, and why did they decide to go?

DS: We moved to the US in 1994, when I was nine. Like many families at the time, my parents wanted to build a better future. Georgia was extremely unstable, and leaving felt like survival.

The culture shock was huge. I still remember walking into a US supermarket for the first time — the variety of food, the brightness, the abundance. That image has stayed with me all my life. There were many “firsts”: first time seeing long suburban neighborhoods, first walk-in closet.

My sister and I missed Georgia terribly. We used to go into that walk-in closet, turn off all the lights, light a candle and pretend we were back home during a blackout. It was our way of carrying Georgia with us — although I’m very happy we didn’t burn down the apartment.

Sighnaghi, Georgia, 2005. Fog in the Kakheti region, an area known for its misty weather.

HM: So why did you return? Georgia was still chaotic then.

DS: Yes, it was. The turning point came when my father asked me to read something in Georgian. I struggled to get through a single sentence. I couldn’t really recognize the letters anymore. That scared my parents.

They had grown up under the Soviet regime, through occupation and repression. My dad often told me stories about that time, and about his grandfather Samson, who was a cinematographer and spent 12 years in exile in Siberia and Gulag prison. He was sentenced to death for being involved in an anti-Soviet underground organization of filmmakers and writers — and somehow survived.

My parents didn’t want me to lose my language or identity. So, even though the future in Georgia was uncertain and harsh, they made the very difficult decision to move back. It must have felt like walking back into the storm.

Daro’s friend, Ana, 14 years old, standing atop the ruins in Gldani district, Tbilisi, Georgia, 1999, during a day they skipped school.

FINDING A VOICE THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHY

HM: What was it like for you personally, coming back to Georgia as a teenager?

DS: It was tough. I was thinking in English and couldn’t fully express myself in Georgian. I had a strong accent, and when I spoke, people would laugh or giggle. Once or twice it’s funny, but after a while it just makes you want to be quiet. I developed a kind of silence around myself.

That’s exactly when photography came into my life. I was about 14 when I first held a camera. From that moment, it became my way of speaking to the world. I skipped school a lot, wandered around our district and photographed everything: family, friends, the streets, daily life.

The camera became an extension of me. If I left the house without it, I felt like I was forgetting my ‘head’. Looking back, becoming a photographer was not a deliberate “career” choice. It was survival, then it became a language.

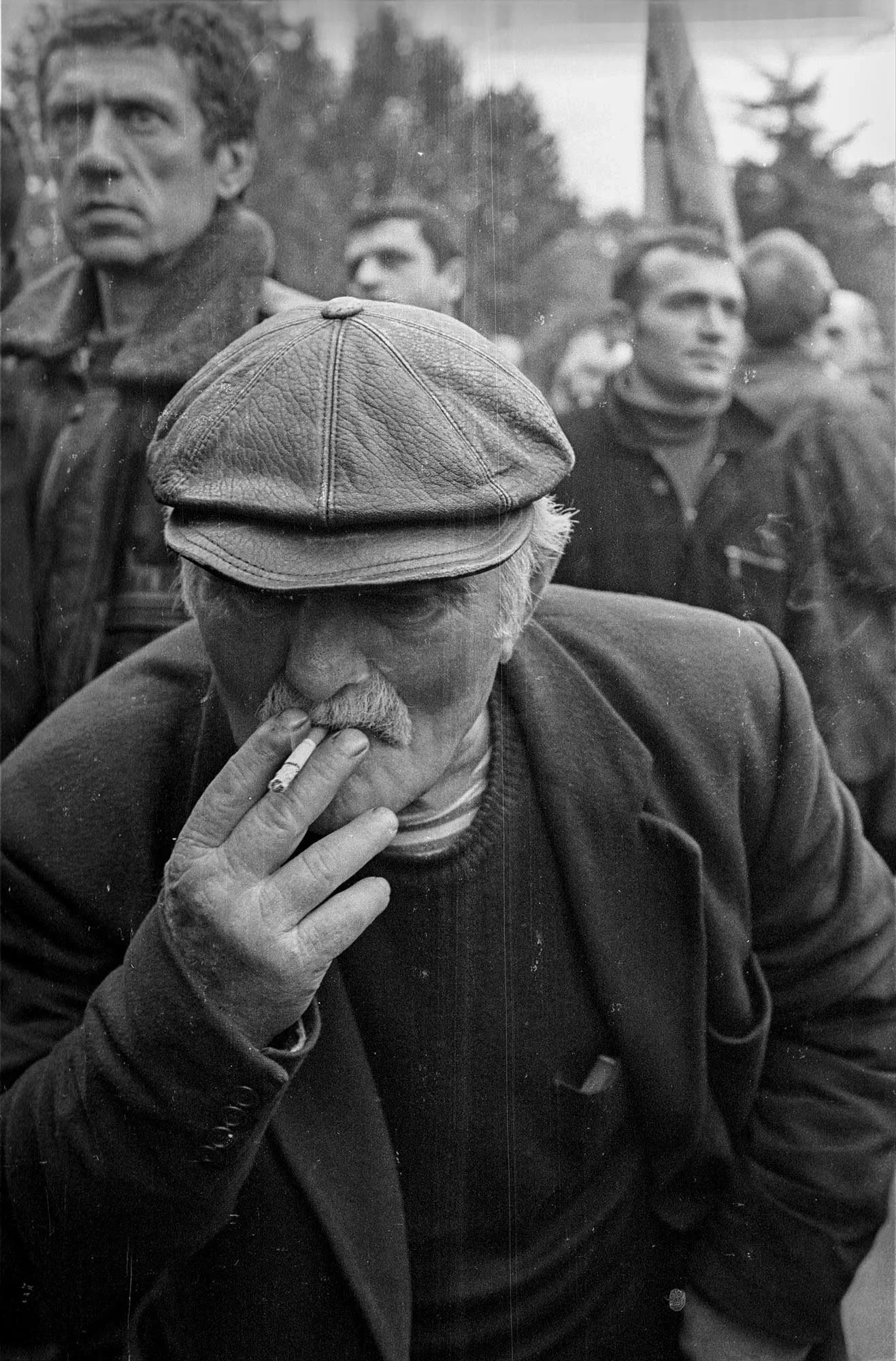

Tbilisi, Georgia , 1999. A man smokes a cigarette during a protest in front of the parliament building.

FAMILY INFLUENCE AND SEEING DIFFERENTLY

HM: You talk a lot about your parents’ influence. How did they shape your vision?

DS: In many ways, they’re the foundation of my work.

My father always encouraged me to think differently, to look at the world with my own eyes and form my own opinion. He would say: “When everyone is looking left, you should look right.” That line is basically the root of my photography.

My mother played an equally big role. She worked to revive traditional Georgian crafts — felt-making, carpet weaving — at a time when these traditions were disappearing. She travelled all over Georgia to very remote villages, trying to persuade women to start weaving and felting again.

She often took me with her. We visited some of the poorest, most isolated villages. People there lived in extreme poverty, but they welcomed us with incredible warmth. They had almost nothing, yet they shared everything: food, stories, time. That changed the way I saw my own life. It made me appreciate small things and understand dignity under hardship.

I think my work today is, in a way, my attempt to give back — to thank those people by telling their stories.

Alvani village, Kakheti region, Georgia, 1999. Tushetian woman Daro, plays a garmon with portraits of herself as a child hanging in the background.

TEACHERS, DISCIPLINE AND EDITING

HM: You later studied photography in Tbilisi and then at ICP in New York. Was there a particular teacher who really shaped you?

DS: Yes. Interestingly, the teacher who most shaped me was in Tbilisi, not New York. He taught me the basics, but also something very important: how to edit my own work.

We shot film then, so we had contact sheets. He would take a marker, circle the frames he thought were good, and put an exclamation mark next to the ones he thought were really good. We were not allowed to argue. If he circled a frame, that was it.

It sounds harsh, but over time it trained my eye. You start asking: Why this image and not that one? What makes this frame stronger? It built an internal editor in my head. Even now, when I’m editing, I feel that influence.

Later, at ICP in New York, I went specifically to study visual storytelling. It gave me a strong base: how to structure a story with 10–15 images, what needs to be in there, what doesn’t. I don’t follow those “rules” literally now, but they gave me a framework to push against.

THE CHECHEN REFUGEES: BREAKING A STEREOTYPE

HM: Let’s talk about your first major project: the Chechen refugees in Pankisi Gorge. Why did you choose that story?

DS: That project was a turning point in my life.

At that time, in 2007, Pankisi Gorge in Georgia was considered one of the most dangerous places to go. Around 5,000 Chechens had fled the war in Chechnya and settled there.

My great-grandmother was Chechen, and I grew up hearing stories about her, I had this image of her in my mind, and I wanted to know more about Chechen culture and traditions.

But in Georgia then, the word “Chechen” had become a synonym for “terrorist.” They had a very bad reputation. I wanted to show something else: their daily lives, their ordinary struggles, their humanity. I wanted to destroy the stereotype.

When the story was published and started winning awards and appearing in magazines, I began receiving emails — this was before Instagram and Facebook — from people saying, “Thank you for showing Chechens differently.” That’s when I understood that photographs can change the way people think on certain topics. That realization shaped everything that came after.

Pankisi Gorge, Georgia, 2008. A boy named Omaar, at a kindergarten in a Chechen refugee settlement. Omaar was left in the care of his grandmother after his family was killed during the Chechen war when he was a baby.

A Chechen Refugee Settlement, Pankisi Gorge, Georgia, March 2008. A Chechen woman, Iase, with her daughter. During the war in Chechnya one of the bombs hit Iase's house in Grozny, the capital. She lost her home. Left in the streets, she followed the rest of the Chechens escaping to Georgia. Crossing the border she ended up in the Pankisi Gorge where she settled. She is still hoping to return home one day.

Pankisi Gorge, Georgia, January 2008. Children at a kindergarten in a Chechen refugee settlement sometimes share a bowl of soup during lunch due to limited food supplies.

TURNING TO TABOO TOPICS

HM: From there, you focused more and more on taboo issues in Georgia: early marriages, mine workers, minorities, the healthcare system, the border with Russia. Why these subjects?

DS: Once I saw that photography could shift how people think, even slightly, I wanted to use it on topics that really needed attention in my own society.

I focused on early marriages, mine workers, stories about minorities, and now the “stolen babies” scandal. All of these topics are painful, but also deeply rooted in Georgian culture and history.

The way I choose stories is that I need the topic to be relevant now, in this moment. When a topic feels like it belongs to another time, I don’t like to go back to it just because a project was once successful.

EARLY MARRIAGES AND BACKLASH

HM: Tell me about your project on early marriages. How did that begin, and what happened after it was published?

DS: Early marriages were, for a long time, a hidden but widespread reality in Georgia. There were also kidnappings — a man would kidnap a girl and then the family would be pressured into accepting the marriage. In many families in Georgia it was “tradition” to marry young: the great-grandmother married that way, then the grandmother, then the mother, then the daughter. It reproduced itself generation after generation.

When my story on early marriages was published in National Geographic, the reaction was intense and mixed. On one side there were hundreds, maybe thousands of people criticizing me: harassing me online, asking why I was “showing Georgia like this.” On the other side, there was another group saying, “Finally someone is talking about this.”

The topic started a dialogue and it told me the story was touching a nerve. People were debating, confronting reality, arguing. That’s when I felt the work had done something.

The story helped influence public opinion and, eventually, policy. In 2019, Georgia raised the legal age for marriage to 18 and introduced restrictions on the age gap between a minor and their spouse. I can’t say my work alone caused that, but I know it contributed to the conversation. I’m very proud of that.

Kakheti region, Georgia, 2005. A 17-year-old bride leaves for her wedding. She met her groom only a month earlier, and while still in school, her age was sometimes reported differently by parents to facilitate early marriage. Her parents are visible on the right, looking out from a window.

Orja Village, Samtskhe – Javakheti region, Georgia, 2013. Khanum, 18 years old, dances for her friends and neighbors at her house. Khanum was kidnapped twice for forceful marriage. Her father managed to get her back, regardless that it is considered a disgrace if the girl returns home after she has been kidnapped. She now sits at home and is unable to attend University, for her father fears that she will be kidnapped again. From a photo project and documentary movie "Double Aliens".

When a teacher leaves the classroom for couple of minutes, 8th graders gather to look at pictures of their friend's wedding party on a mobile phone in a village school in Samtskhe Javakheti region, Georgia.

Kakheti Region, Georgia, 2014. Bride and Groom. Bride 17 and groom 22. Wedding day. It is common in remote villages for the girls to get married at a very young age.

THE MINES OF CHIATURA

HM: You also spent time photographing mine workers in Chiatura. How did that project unfold?

DS: Chiatura is a manganese mining town in terrible condition. Many miners work in extremely harsh, almost Soviet-era conditions with equipment dating back to the 1950s and 60s.

I had seen photography on Chiatura before — portraits of miners, cityscapes, atmospheric images. But I hadn’t seen anything from inside the tunnels, where the actual work happens. I wanted to show that world.

I befriended miners and hired one former miner as a fixer. Together we would go to the mines at midnight and sneak inside the tunnels with the workers. I photographed how they worked, what they ate, how dangerous the environment was. It was physically and emotionally tough.

When the work was exhibited and published in National Geographic, the mining company called me. They were very unhappy and basically tried to pressure me into taking the story down. They suggested that I come and see “the reality” according to them. I agreed, went back to Chiatura, and called them from there — and suddenly they couldn’t show me anything.

The conversation ended with us agreeing that we wouldn’t agree. It was calm, even polite, but firm. Afterward, they placed security guards at the entrances to all the mines, so no one could easily go in anymore. In a way, that reaction confirmed that the work had hit a painful truth.

Chiatura City, Georgia. A mineworker sits in a mining train on its way down to the tunnel, working 12-hour shifts for approximately $300 per month.

Chiatura City, Georgia. A miner works in the manganese tunnels. Due to fears of retaliation over poor working conditions, the miner’s face was partially hidden with a flashlight to protect their identity.

Chiatura City, Georgia. The homes of miners show damage caused by shockwaves from underground mining explosions.

Chiatura City, Georgia. A cable car system dating back to the 1950s runs along the city's vast gorges. The cars were used to transport miners but today they are also used as public transportation for the locals. Here, a cable car controller works the night shift.

THE STOLEN BABIES

HM: Let’s talk about your current long-term project, which is extraordinary and disturbing: the “stolen babies” scandal. How did you first discover it?

DS: It started near the end of the pandemic. I stumbled on a Facebook group created by a Georgian woman who had found two birth certificates after her mother died. She suspected she might be a stolen baby. She and a group of other Georgian women started the Facebook group to look for answers.

Today, hundreds of mothers, fathers, and adult children follow that group. Every day there is a new post: “I am looking for my son,” “I am looking for my daughter,” “I am searching for my mother,” “my father.”

The mothers who were writing their stories in the group had similar stories, they were told by doctors that their baby had died a couple of hours later, but the mothers never saw the body, never saw a grave. It turns out there was an organized system, with different schemes around the country. It happened during the political and economic turmoil of the 90s and 2000s, when a black market baby trade flourished in Georgia. Corrupt doctors, nurses, and traffickers stole infants from the hospitals and sold them through an underground criminal adoption network.

Medical staff gave different stories about the supposed deaths: some mothers were told their babies died from respiratory failure, while others were told they died from organ failure. In every case, doctors promised to bury the babies in a hospital graveyard, graveyards that did not exist. That detail alone is chilling.

What began inside Georgian hospitals extended far beyond the country’s borders. The network was tied to adoption agencies not only in Georgia, but also in the United States, Canada, Israel, Cyprus, where babies were funneled into legal systems through forged documents.

My investigative project, Stolen Babies, uncovers these hidden operations and investigates Georgia’s systemic trafficking of newborns, many of whom have been erased from records over decades.

Today, DNA testing has become a key tool. People are finding each other — parents finding children, siblings finding siblings — through DNA databases. But the people who committed the crimes are mostly walking free. Some of the doctors and officials involved still hold powerful positions.

An aunt is hugging her long lost nephew, Giorgi, for the very first time on March 18, 2023, in Zestaponi, Georgia. Giorgi Siradze, 29 years old, was born in Zestaponi hospital and was declared dead by the doctor, when in reality he was sold for adoption. Decades later, a former nurse’s confession to a priest finally unraveled the mystery: Giorgi Gureshidze, declared dead by the hospital, was alive, adopted by a family in another city. The Siradze family’s nearly three-decade-long nightmare had finally ended when the priest informed the family that Giorgi was alive, unable to reveal the identity of the nurse.

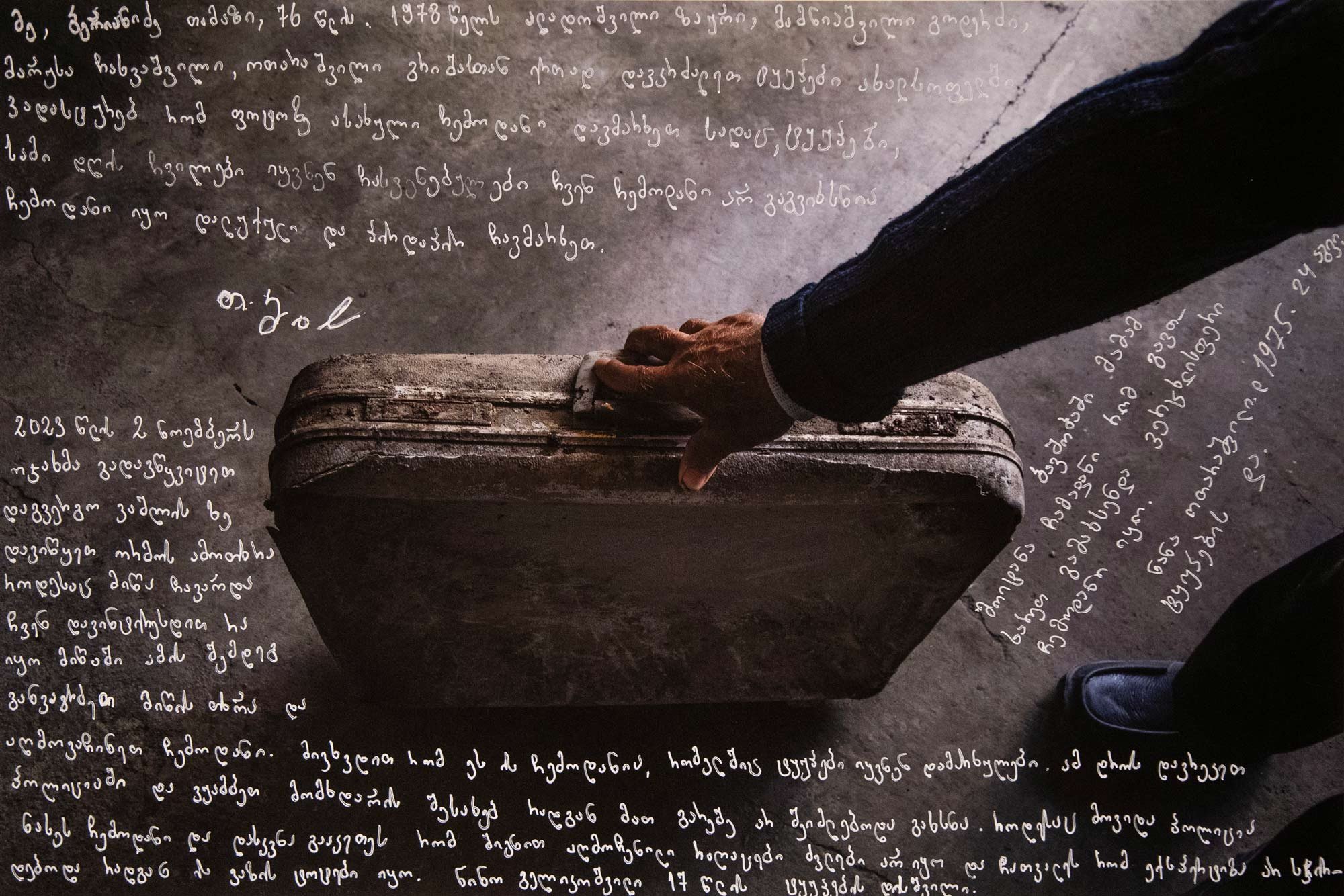

Irina Otinashvili gave birth to her twins, but after a couple of hours the twins were declared dead by a hospital doctor. Medical staff asked the father to bring a suitcase so the twins could be buried. The suitcase then was given to the twins’ father by medical staff closed and locked for burial. Years later the twins mother became suspicious if her babies really died or were sold. She exhumed the suitcase and called the Georgian police, who stated at the scene that it contained only remains of vine branches inside. Daro asked the witnesses who are alive today to write on the photograph as proof that they witnessed the suitcase being buried and never saw what was inside. May 16, 2023, Akhalsopeli village, Georgia. The photo is from an investigative story on the stolen and trafficked babies of Georgia.

HM: You’ve mentioned that the authorities are not eager to investigate this properly. What are you hoping your work can achieve?

DS: I hope it can create enough pressure that the government and police are forced to act: to open archives, release records, and formally investigate. There are still living witnesses, and there are still people in power who were involved. That’s one reason the topic is so sensitive. Everyone protects “their” people.

I’m cautious. It’s dangerous to name names without institutional backing. Ideally, I’d like to have some kind of protection or support from authorities if I publish certain details. Right now, families are doing the work themselves — paying for DNA tests, hunting for documents — while those responsible enjoy impunity. That feels unbearable.

The stories are astonishing. For example, there are twin sisters in Georgia who found each other through TikTok. One of them posted a video of her newly pierced eyebrows. A friend of the other twin saw it and said, “This girl looks exactly like you.” They contacted each other, and it turned out they were twins, sold to two different families in two different regions. Growing up, they both had the same recurring dream of a small child watching them from a far.

There’s also the case of Panagiotis, a man raised in Cyprus. His documents are clearly forged; the names of his supposed biological parents are made up. Through his case, we realized how this one woman was operating under the cover of international adoption, with a whole chain of complicit doctors and officials.

Some nurses, near the end of their lives, have begun to confess. One nurse confessed to a priest that she knew where a particular boy had been sold; a family had been searching for their son for 29 years. The priest couldn’t reveal her name but gave enough clues for the family to find him. These tiny acts of conscience are slowly unraveling a huge crime.

Portrait of Nana in her home in Mtskheta, Georgia, September 09, 2025. “I feel like half of myself is missing,” says Nana, who believes her daughter is still alive. She’s convinced that the doctors lied to her, that her baby didn’t die after birth, as they claimed. Nana gave birth to her daughter in 1992. “I heard my baby cry when I gave birth. The nurses told me they couldn’t show me my baby because she was so tiny. I had high blood pressure, and everyone was focused on me,” recalls Nana. On the third day, Nana’s husband wanted to name the baby and requested the documents, but was told that their child had died and there was no need to name her. When he asked the doctor what went wrong, the doctor replied, “Worry about your wife, not the child. You can have another one.” “They told us they could give us our dead baby, but it would be better if they buried her in their graveyard so we wouldn’t stress about it,” she continues. Many years later, they discovered that no hospital in Georgia ever had graveyards. On the seventh day, Nana was discharged from the hospital. “I’ve always felt my daughter is alive. I know I will find her one day; I’ve dreamed of her for years.” Two years ago, Nana began her own investigation. Upon requesting any kind of documents from the hospital archive, she discovered that her baby had been named by someone else, and there were no documents proving her daughter had died.

RESEARCH, TRUST AND COLLABORATION

HM: Your projects are long term and very deeply researched. How do you begin? How do you organize a story like this?

DS: I always start by reading. For the stolen babies project, I spent a lot of time in libraries, digging up old newspapers. I wanted to know if anyone had written about this in the 90s. And they had — there were articles. But people read them, got upset for a week, and then forgot. One librarian looked at me and said, “Why are you researching this? Everybody knew babies were being sold.” That sentence really stayed with me: everybody knew, and yet nothing changed.

But research on a computer is never enough. I go to the regions, I knock on doors, I sit in kitchens, I listen. Often, one person leads me to another. The story grows organically like a web.

Nini, a resident of the village of Khurcha, leans on a windowsill near the southeastern borderline of the Russian-supported separatist territory of Abkhazia. Georgia, 2017.

HM: These are intimate, painful stories. How do you make people trust you enough to share them, and to allow you to photograph them?

DS: Respect and honesty are everything.

When I meet someone, I don’t take out the camera immediately. I talk. I explain exactly what I’m doing, why I’m doing it, and how their contribution might help. My camera is visible — I don’t hide it — but it isn’t the first thing I “use.”

I like to collaborate with the people I photograph. In my Shifting Borders project about the conflict with Russia, for example, I asked people to write letters to me. Those letters became part of the work. It’s not just me “taking” their stories; they are co-creating how the story is told. That gives them agency and deepens the narrative.

Orsantia village, Georgia, 2017. A child takes a swim in the Enguri River, which is used as the borderline of the Russian-supported separatist territory of Abkhazia. The river was previously known as a good location for safely crossing into Abkhazia, but recent installation of barbed wire fencing and surveillance equipment has slowed those crossings. The border marks on the photo illustrate the words of a local, when she had a small dialogue with a Russian militant standing in a watchtower that overlooked her house near the Enguri river. “I took my grandkids out for a swim on a hot summer day, when the kids were already in the water, one of the Russian militants from the watchtower addressed me to keep the distance, I asked why? He said in Russian that half of the river belongs to Russia and half to Georgia”.

Georgia, 2017. A family stands near their corn field in Pakhulani village.

Tatia Adikashvili with one of their children at the border of the Russian-occupied Khurvaleti village. Tatia waits in the police car , while his husband hands a gallon of drinking water over the fence to his mother, who has none on her side. Escorted by a Georgian guard, they avoid arrest by the occupying forces – what they've experienced before.

A CINEMATIC EYE AND THE “DECISIVE MOMENT”

HM: When I look at your photographs, there’s often something cinematic about them — in the way you frame and build the scene. Are you conscious of that when you’re shooting? What goes through your mind when you press the shutter?

DS: I’ve thought about this a lot: why this moment and not another? Why do I press the shutter when I do?

In the moment itself, I’m not consciously constructing compositions in a technical way. I’m very present. I feel the scene, the tension, the emotion. When I press the shutter, it feels like everything from my life is compressing into that fraction of a second — my childhood, the chaos of the 90s, the films I’ve watched, the books I’ve read, the stress, the stories I carry.

I work a lot with intuition — with what people call the “decisive moment.” I believe what makes a photograph uniquely yours is that invisible accumulation of your experiences, all arriving at the moment you decide to press the button.

Pankisi Gorge, Georgia, May 2008. Chechen boys at a refugee settlement. With no jobs and lacking legal documents, young men cannot leave Pankisi to find work. Since December 1994, when war broke out between the Russian-backed central government in Grozny and a determined group of Chechen resistance fighters, Pankisi has witnessed an influx of refugees from Chechnya. Though not recognized or officially monitored by international agencies, Pankisi has become a refuge from state-sponsored terror for thousands of people who, ironically, are accused of waging terror at home. Chechens have a reputation for rugged individualism, even among the peoples of the Caucasus who – by any standards – are accustomed to rugged conditions and nurture a fierce sense of national pride and independence in light of the imperialist tendencies of surrounding nations. By most estimates, approximately 5,000 Chechens escaped the deadly war in Chechnya by fleeing to Georgia's Pankisi Gorge.

COLOR VS BLACK AND WHITE

HM: You started with black and white film, but much of your work now is in color. How do you decide whether to use color or black and white?

DS: In the beginning, I had no choice — we only had black and white film. I walked around seeing the world as frames in black and white. It was actually a strange experience: I would walk down the street and “see” the scene in monochrome.

Then one day my teacher gave me a roll of color film. When I saw the results, I thought: This is how I actually see the world. I never went back. Color felt more honest to my perception and more challenging in an interesting way. You have to control the chaos of color: too many colors can make an image messy, so you learn to understand how they work together, how they carry emotion and symbolism.

Aspindza children’s orphanage, Georgia, 2002. A young girl during mealtime in the cafeteria.

BEING A WOMAN, BEING AN “ACTIVIST”

HM: As a Georgian woman documenting women’s experiences and other vulnerable communities, do you feel your perspective gives you access to stories that others might overlook?

DS: Overall, it has given me certain openings. At the same time, I want to emphasize that my access isn’t only because I’m a woman. Over the years, I’ve also built deep trust with men in communities like Pankisi. Earning that trust took patience, honesty, and time, showing up again and again, listening more than speaking, and respecting their boundaries.

So while my perspective as a woman shapes how people receive me, the real access comes from the relationships I’ve built and the trust I’ve earned with everyone, regardless of gender.

Kirbali Village, Georgia, Nov 11, 2023. On November 6, 2023 Georgian Tamaz Ginturi was shot dead at the Lomisi Church near Kirbali. The church, located in the South Ossetian conflict zone claimed and controlled by Russia, had been barricaded by the occupiers. A video, believed to be taken with Tamaz Ginturi's phone and circulating on social media, shows him and Levan Dotiashvili forcibly entering the church before Russian forces opened fire. Dotiashvili was captured and Ginturi was killed. On November 8, Tamaz Ginturi’s body was laid out in his home village of Kirbali.

HM: Do you see your work as a form of activism?

DS: I have spent a long time thinking about whether I see myself as an activist.

I can’t resonate with the word “activism” because I don’t organize campaigns or take direct political action. I see myself as a photojournalist and visual artist. With my work, I tell stories and I believe photography can alert people and awaken awareness.

In that sense, my work touches activism, but I approach it through storytelling rather than activism itself.

Tbilisi, Georgia, May 26. Riot police clear protesters from the streets, using tear gas during the demonstrations.

Georgia, Tbilisi, 2012. Tens of thousands of Georgians took to the streets of the capital Tbilisi on Sunday to protest against the government of President Mikheil Saakashvili.

TRUTH, MANIPULATION AND THE AGE OF AI

HM: Since you started, the technology around photography has changed dramatically — digital cameras, phones, social media, and now AI. Do you see these changes as a threat, an opportunity, or both?

DS: Both.

On the one hand, I worry that future generations might lose the ability to sense what’s real and what’s not. My generation still has that gut feeling; we grew up with physical reality being more dominant than screens. When I look at an AI-generated image, I can often feel that something is “off,” that it lacks the messiness of life.

On the other hand, we all now have a responsibility to be extremely careful about sources — to double and triple-check what we see. Social media is another double-edged sword. It’s an amazing tool for sharing work and reaching people, especially for independent photographers. But the endless scroll can be numbing. You see a horrific image from a war, then a dancing video, then an ad, then a meme — all in seconds. It flattens emotional response. I feel it in myself: the more I scroll, the harder it is to feel deeply.

Tbilisi, Georgia, 2013. A female patient at a psychiatric clinic participates in an art therapy session, dressing in a red costume. She prefers to remain anonymous.

WHAT’S NEXT

HM: What’s next for you? What are you working on now?

DS: For the next six months at least, I’m fully committed to the stolen babies investigation. Recently I received a grant from François de Mulder, which is a big encouragement — not just financially, but emotionally. Grants are crucial. Without earlier grants, I couldn’t have done the Shifting Borders project in the way I did. Awards celebrate past work; grants enable future work. They allow you to go deeper instead of rushing from assignment to assignment.

Mari Meladze, 18, poses near the occupied territory of Georgia's South Ossetia region in the village of Odzisi, Georgia, August 19, 2022. On that day, the de facto South Ossetian authorities announced they would reopen the Odsizi/Akhalgori checkpoint after three years, for 10 days per month. "My village is so isolated," she said. "When the checkpoint closed in our village, many were left isolated from their family members. After three years, the checkpoint is open, and locals can relocate between the regions. For relocation locals need a special pass which has an expiration date. After the expiration date, the holder of the pass is not guaranteed to get extension of the pass. This makes it hard for anyone who works in the regions or has a small business."

ADVICE TO YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHERS

HM: What advice would you give to young photographers who want to do documentary or photojournalistic work — especially on difficult social issues?

DS: First: start with empathy. Really care about the people you photograph. They’re not “subjects” or “characters”; they’re humans whose lives you’re entering.

Second: understand your responsibility. How you show someone can affect their life and how society sees them. Think carefully about what you publish and why. Are you dignifying them or using them?

Third: think intellectually about your stories. By that I mean don’t just rely on instinct; also use your brain. Ask yourself: What is the most meaningful way to tell this? Should I bring in other mediums — text, audio, video, letters, archives? How can I engage people long enough that they won’t just scroll past?

And finally: don’t wait at home for an idea to magically appear. Go outside. Read. Talk to people. Travel, even if it’s just to the next neighborhood. Often a story begins with one sentence someone says in passing. You have to be out in the world to hear it.