Unseen Places, Unsettling Realities: A Conversation with Gregor Sailer

Gregor Sailer (born 1980) is a photographer working in the fields of art, science and architecture. His work explores how buildings and structures can represent economic, political and social ideas, and he often creates images in remote or hard to access locations.

From 2002 to 2007 he studied Communication Design at the Dortmund University of Applied Sciences and Arts, specialising in photography and experimental film. He also completed a Master’s degree in Photographic Studies there in 2015.

Sailer’s works have won multiple awards and have been shown nationally and internationally in solo and group exhibitions, including in New York, London, Arles, Milan, Vienna, Prague, Berlin and Budapest. Many of his photo series have been published as photo books, most recently The Polar Silk Road, The Box and Unseen Places. He lives and works in Tyrol, Austria.

© Patrick Saringer

GROWING UP IN TYROL

HM: You grew up in Tyrol. Was it a village, a town? What kind of place shaped your childhood?

GS: I grew up in a village – when I was a child it had around 1,500 inhabitants. Today it’s grown to about 4,500, so you could call it a large village, but it’s still not really a city. It lies in the main Inn Valley, about 20 kilometres before Innsbruck.

Most people in this valley traditionally worked in farming, and that’s still present, but over time it has become one of the most densely populated areas in Europe. The villages have grown together so much that the valley feels almost like a continuous urban zone, even though it still looks “rural” in many ways.

There are a few bigger employers, like Swarovski – their headquarters are about ten kilometres from my village and they employ several thousand people – but apart from that it’s small businesses. It’s not an industrial region in a classical sense. But tourism plays a major role in Tyrol.

DISCOVERING PHOTOGRAPHY

HM: How did photography enter your life in such a rural environment?

GS: In a place like that, photography was understood as wedding pictures and studio portraits – nothing more. So when I said I wanted to be a photographer, almost nobody understood what I meant.

I started quite early. Around 1990 I got a small compact camera – a black, little thing – and that was the beginning. At about 16 or 17, I created my first “story”.

After high school graduation came compulsory service. In Austria we don’t have a professional army, so you choose between the military or civil service. I chose civil service, which meant almost two years where photography could only run in parallel. After that I went to the Prague School of Photography, and a vocational track in photography, to get proper technical training.

But fairly quickly I realised: this wasn’t enough. I didn’t just want to learn how to handle a camera; I wanted tools to tell stories, to think conceptually.

LEAVING THE MOUNTAINS: STUDYING IN GERMANY

HM: At some point you left Tyrol and went to Germany to study. Why, and where did you end up?

GS: For a while I was fixated on staying close – Munich, Bavaria – but I wasn’t accepted at the university there, and I lost two years waiting and trying again. At 21 I finally understood: if you want to grow, you have to leave the mountains and forget the borders in your head.

I eventually landed in Dortmund. The university there suited me very well. It wasn’t just photography; there was graphic design, film, spatial and object design, and you could move between disciplines. That was important – I didn’t want one professor who decided what was “good” and “bad”, I wanted a broad spectrum of teachers and influences.

The Ruhr region itself, with cities grown together into a big urban zone of more than four million inhabitants, was also an education: lots of museums and a strong visual scene, but also post-industrial decline, unemployment, frustration, right-wing radicalism and social tensions in the streets. It was exhausting, but crucial for me to experience.

Later I did a second course of study also in Dortmund while already having two daughters and living 1,000 kilometres away in Tyrol. I commuted back and forth. It was challenging, but it shaped my practice profoundly.

CHOOSING ARCHITECTURE INSTEAD OF PEOPLE

HM: Many photographers work with portraits and human stories in a direct way. You chose to focus almost exclusively on architecture and built structures. Why?

GS: It’s not because I dislike people – quite the opposite. I need people, their experiences and conversations. But I come from a family where architecture was always present: my father is an architect, so we grew up with floor plans and models on the table.

I have done portraits and editorial work for magazines, but my passion is to tell stories through architecture. I’m interested in structures that are strong enough, symbolically and visually, to carry complex social and political narratives.

I’m not a “ruin” photographer or a hunter of abandoned places. The locations I photograph are almost always in use, inhabited, or operational. Very often there is a serial or repetitive character to these environments. By leaving people out of the frame, this serial, almost abstract quality becomes stronger – yet the viewer knows that people do live or work there. That tension interests me.

WHY RESTRICTED AND “FORBIDDEN” PLACES?

HM: A lot of your projects focus on restricted or forbidden places – military installations, closed cities, secret industrial sites. Why are you drawn to these zones?

GS: It’s not because “forbidden” automatically equals “spectacular”. The starting point is always the subject: a story, a development, a phenomenon that I find important to explore.

During research I often realise that these stories unfold in restricted areas – military zones, corporate sites, closed cities – and that’s why I end up there. Such places also offer the possibility of finding images that don’t already exist a thousand times on the internet. The more accessible a place is, the more images there already are.

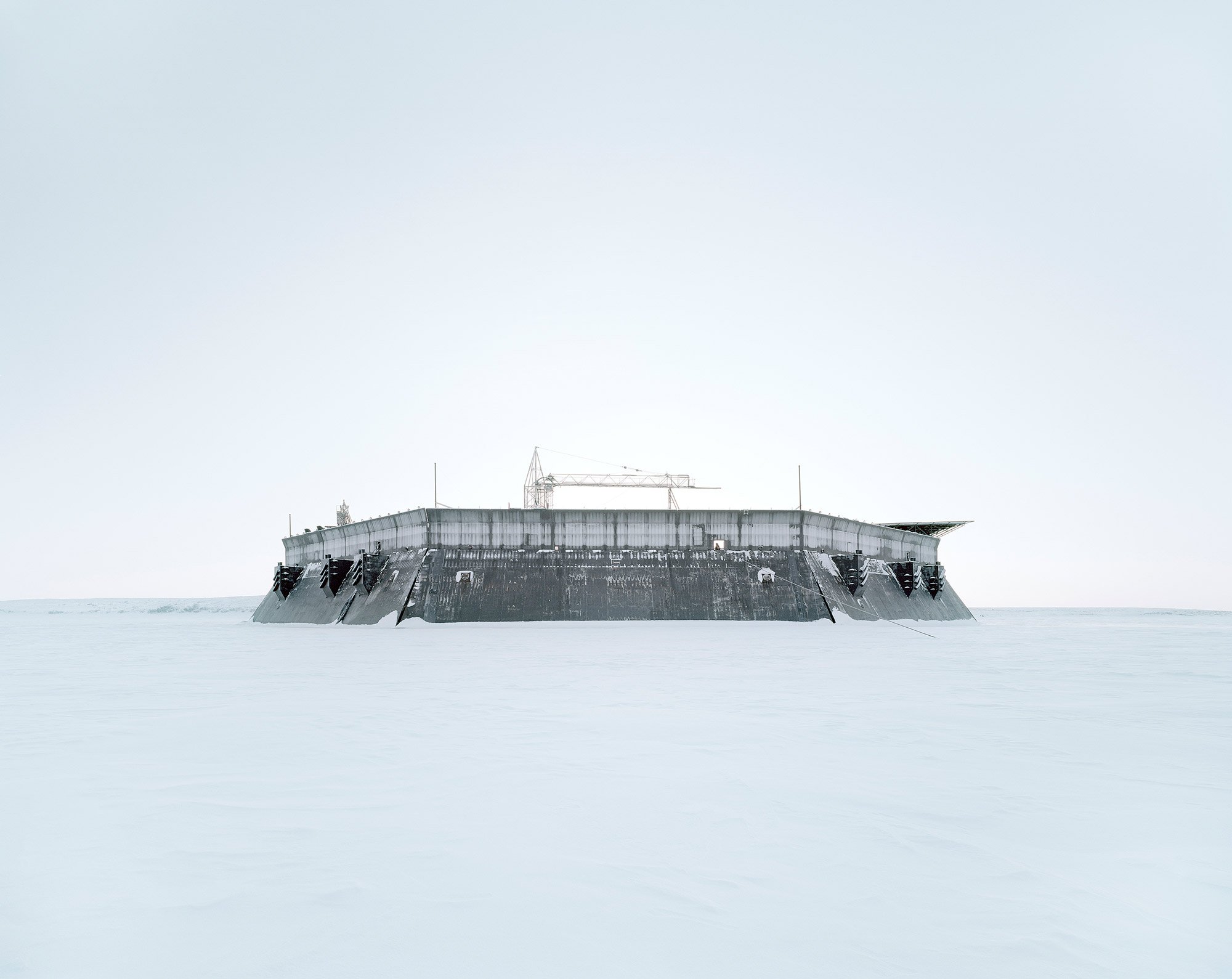

Take my project on the Polar Silk Road, for example – the emerging trans-polar shipping routes and the huge military and research infrastructures around the Arctic. It’s an extremely political topic. Many of the structures there are military, or scientific facilities embedded inside military zones. If you want to photograph them, you automatically confront secrecy and restrictions.

Another reason I avoid showing people in these locations is censorship. I’ve had to learn very early how to work under systems where you are not allowed to publish images without permission. If I showed identifiable people in sensitive areas, it would be far harder – sometimes impossible – to get clearance. My goal is to tell difficult stories, not to block myself from future access.

POTEMKIN VILLAGES: ILLUSION VS. REALITY

HM: Your project The Potemkin Village plays with architecture as illusion. Are you more interested in the buildings themselves, or in the psychological and political intentions behind them?

GS: Both – and especially in the way they interact.

In the book and exhibitions, there’s a deliberate dramaturgy: the work moves constantly between illusion and reality. Sometimes it’s obvious that a place is fake – a training town, a mock façade – sometimes the border becomes blurred and you start to ask yourself, Is this real?

I began with the historical legend of Potemkin building fake villages for Catherine the Great, and then I searched for contemporary equivalents. I went to Russia, where new Potemkin villages were constructed for political events like the BRICS summit in Ufa. From there I expanded the research: military mock towns for urban warfare training in the US, France, Germany, the UK; fake towns in China built as real-estate fantasies that ended up as ghost towns; test sites and camouflage architecture.

I wanted to know: how do different nations’ current conflicts and fears shape the architecture of these mock cities? In the US, many training sites imitate Middle Eastern or Afghan architecture; in Europe they often simulate European cities, because armies expect more conflicts on their own streets.

I don’t give simple answers – I can’t say “this is right” or “this is wrong”. What I can do is create a visual platform that makes these illusions visible and invites discussion.

GETTING PERMISSION AND DEALING WITH FRUSTRATION

HM: Accessing underground submarine bases, restricted military terrains or big energy companies is extremely difficult. How do you actually get permission to photograph in these places?

GS: That’s one of the hardest parts of my work, and a major reason why my projects take three to five years. The research and organisation phase is often much longer than the actual photography.

To give you an example: an underground naval base for submarines in Norway. It took more than four years of applications, emails, phone calls and negotiations before I finally received permission. When I entered, it felt like walking into a James Bond set – but it was real.

Very often you invest months of work, and in the end one person high up the chain says “no”. Then everything collapses and you have nothing to show for it. That can be extremely frustrating.

The key is consistency and patience. I need to find at least one person inside the institution – an officer, a communications person, a scientist – who is genuinely interested in the project and not just thinking in terms of money, because I can’t pay for access. I finance everything myself.

On top of that, I’m always dependent on the political situation in a given country. Permissions that were easy during one government can become impossible under another. You feel geopolitical shifts very directly.

THE CALM IMAGES AND THE ABSENCE OF PEOPLE

HM: Your photographs are rigorously composed and very calm. There are never any people in them. What does this stillness mean to you?

GS: For me the photographs are about reduction. I want to remove everything that distracts from the built structure itself: no movement, no visible emotions, no random detail if I can avoid it.

I don’t digitally manipulate my images – I don’t erase people or cars afterwards. I wait until the scene is as I need it to be. That makes the process slow and sometimes nerve-racking, especially in places where my time slot is very limited. But this slowness is important: it builds concentration and presence.

I strongly believe you can convey emotion purely through architecture – through light, space, proportion, context. In a refugee camp, for example, it would be easy to show suffering by photographing faces and gestures. Many photographers do that, and it is important. My decision was to go the opposite way: to show the conditions in a very reduced, almost neutral way, and let the viewer slowly discover the horror behind that apparent calm.

WORKING WITH A LARGE-FORMAT VIEW CAMERA

HM: Technically, how do you work? Are you using 35mm, medium format, digital?

GS: All my independent long-term projects are shot on a large-format view camera, 4x5 inch – sometimes 6x9 cm medium format – always analog. It’s a heavy studio camera, not the easiest companion for polar storms or deserts.

I usually expose one negative per motif. That is partly financial – film, processing and travel are expensive – but mainly it’s about concentration. If you know you have one sheet per picture, your perception becomes sharper. You look more intensely, you think longer, you compose more carefully.

Working analog also has practical advantages in extreme conditions. In Nunavut, at the Northwest Passage, I had temperatures around –70°C with wind chill. A digital camera would be at its limit; batteries die very quickly. The view camera doesn’t care. Film, however, becomes brittle below –50°C, so I switch to sheet film rather than roll film because I don’t have to bend it.

The other extreme is heat. In northern Kenya, near Kakuma refugee camp, it was so hot that protecting film became almost impossible, and I lost nearly half of my material. That’s the risk of working this way: if something goes wrong in the field or in the lab, the image is simply gone.

PROCESS ON LOCATION

HM: When you finally arrive at a location – after years of preparation – what happens before you press the shutter?

GS: If I have enough time, I first walk the space without a camera. I try to understand the structure, the atmosphere, the relation to its surroundings. Then I decide which aspects best represent the essence of that place.

Only after that do I set up the camera and build the composition. Light is crucial – I need a quiet, soft, often overcast light that connects images shot in completely different parts of the world. Harsh sun creates strong shadows and reflections that destroy the silence I’m looking for.

Of course, reality doesn’t always match my ideal. In Azerbaijan, for the project on closed cities, it took over a year to get permission to photograph Oil Rocks, the huge Soviet-era city on platforms in the Caspian Sea. When I finally arrived, the authorities said, “You have three hours.” For an entire city! And at midday, in full sun.

You can’t just give up. You work with intense concentration, you compromise, and you accept that some things won’t be possible. Preparation can be perfect on paper, and still the situation on site is completely different. That uncertainty is part of the work.

ARCHITECTURE AS A MIRROR OF POWER AND SOCIETY

HM: Throughout history, architecture has projected power – emperors, dictators, ideologies. What do the buildings you photograph tell us about our own society?

GS: Architecture is always a mirror of society. The structures I photograph are direct materialisations of political decisions, economic interests, social tensions and technological developments.

In The Potemkin Village, for instance, you see enormous investments made purely to produce illusions: fake cities for political summits, mock villages for urban warfare training, replica European towns in China built as real-estate fantasies. They show how much energy and money we invest in façades – in staging, simulation, control.

In other projects, like the Polar Silk Road or Closed Cities, architecture reveals geopolitical competition, paranoia, isolation. In all cases I try to choose subjects that are not about a single event or a single day, but about longer processes – developments that stretch over decades and shape the way we live.

AUDIENCE REACTIONS AND EMOTIONS

HM: Your images are very controlled and emotionless on the surface, yet people respond strongly to them. What reactions have stayed with you?

GS: Over the years I’ve seen very different reactions. Some visitors feel uncomfortable, even scared: they say the work is too dark for them. Others are simply astonished – they didn’t know these places exist.

More than once people have started to cry in front of the pictures. That was surprising for me, because I don’t show human suffering directly. But of course the atmosphere, the silence, the emptiness, the knowledge of what these places are used for – all that triggers emotions. When someone stands in front of a very reduced architectural image and begins to cry, I am deeply moved as well.

What I hear often after talks or lectures is: “We had no idea. You really opened our eyes. We’ll never look at these topics the same way again.” That kind of feedback gives me the energy to start the next long project.

THE COMMON THREAD: “UNFAMILIAR PLACES”

HM: Looking at Closed Cities, The Potemkin Village, The Polar Silk Road and The Box – what connects these projects? Is there a single thread?

GS: Yes. On the most basic level, I’m interested in unfamiliar places – spaces that are normally invisible, inaccessible or simply unknown to the wider public – and in how they reflect broader social, political and economic developments.

The catalogue for my retrospective at Kunsthalle Wien was titled Unseen Places, and that sums it up quite well. I’m looking at how historical and current developments change the forms of architecture, and how those forms in turn influence how we live and think.

So whether it’s a secret military training town, an Arctic radar station, a refugee camp or a gigantic railway tunnel under the Alps, I’m trying to make visible what usually stays hidden.

NEW WORK: COCKAIGNE AND THE FUTURE OF FOOD

HM: Your new project deals with the future of food production. Can you tell us about it?

GS: The project is called Cockaigne – not related to cocaine, but to a medieval French and later also Irish legend about the “Land of Cockaigne”, a place of abundance where nobody has to work and everyone has enough to eat.

I’ve been working on it for over four years. The book with about 300 pages has been recently published. The first large solo exhibition opens at the Natural History Museum Vienna on February 10.

The project looks at different methods and visions of how we might produce food in the future. There is a very colourful central part: high-tech farms, AI-controlled greenhouses, insect and algae production, jellyfish as food, cultured meat, huge robotic facilities – all very futuristic, almost science-fiction architecture in pinks, blues, and artificial light.

But I didn’t want to stay only in the comfort zone of advanced technology and wealthy regions. So I also photographed very simple forms of agriculture in extreme conditions:

In the Arctic, far above the polar circle, where Inuit communities use connected shipping containers to grow fresh vegetables as a pilot project – many of them had never seen fresh greens before.

In northern Kenya, in and around Kakuma refugee camp, where people try to gain a little independence from international aid by cultivating tiny plots of land under incredibly harsh conditions.

In Morocco’s High Atlas, where traditional food forests function like self-regulating ecosystems in arid zones – almost forgotten methods that could be part of future solutions.

The book is structured like a film: an opening in the white, wide Arctic “food desert”, the intense, colourful middle part of high-tech agriculture, and a final movement towards the green of the food forest. I’m not saying, “This is the perfect model for the future,” but I want to show that alternatives exist – that we could change the way we produce food if we choose to.

THE BRENNER BASE TUNNEL AND OTHER CURRENT WORK

HM: Parallel to Cockaigne you also worked on the Brenner Base Tunnel between Austria and Italy. What attracted you to that project?

GS: The Brenner Base Tunnel is a century project – when it’s finished it will be the longest underground rail connection in the world, about 65 kilometres, linking Austria and Italy under the Alps. It’s a huge intervention in the landscape and in European infrastructure.

I followed parts of the construction for several years. Again, it’s about spaces most people will never see: enormous caverns inside the mountain, temporary underground cities for workers, a whole world carved into rock. A small-edition book has been published, mainly for decision-makers and politicians, but the work is also being shown in Italy at the moment.

LOOKING AHEAD

HM: After all these projects – closed cities, Potemkin villages, polar routes, future food, tunnels – what keeps you going?

GS: Curiosity, I think. And the feeling that these stories matter. My projects are long and risky; financially it’s often a struggle, and I still work completely independently. Sometimes I really worry how we’ll survive the next year.

But every time I see that the work opens up discussions, when people tell me it changed the way they think about the world, it gives me the energy to continue. As long as there are unseen places that say something essential about our society, I’ll keep trying to photograph them.

For information on Gregor’s upcoming exhibition at the Natural History Museum Vienna head over to www.nhm.at

To get a copy of Gregor’s latest book Cockaigne, please visit www.kehrerverlag.com

All images © Gregor Sailer unless otherwise stated