Mark Edward Harris: Stories Without Borders

After graduating with a Master’s degree from California State University, Los Angeles in Pictorial/Documentary History (a program he developed), photography assignments have taken Mark Edward Harris to more than 100 countries on all seven continents. His editorial work has appeared in publications such as Vanity Fair, LIFE, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Time Magazine, GEO, CNN, Newsweek, Conde Nast Traveler, National Geographic Traveler, Hemispheres, AFAR, Paris Match, VICE, Wallpaper, Vogue, Architectural Digest, The Los Angeles Times Magazine, and The London Sunday Times Travel Magazine as well as all the major photography and in-flight magazines. Among his numerous accolades are CLIO, ACE, Impact DOCS Award of Excellence, Aurora Gold, New York Book Show Book of the Year and IPA awards. His books include Faces of the Twentieth Century: Master Photographers and Their Work, The Way of the Japanese Bath (four editions), Wanderlust (two editions), North Korea, South Korea, Inside Iran, The Travel Photo Essay: Describing A Journey Through Images and The People of the Forest, a book about orangutans.

Mark Edward Harris, Hokkaido, Japan © Jackie Cheng

HM: Mark, could you walk us through your early background? What aspects of your upbringing influenced the person you became?

MEH: I was born in New York, but we moved several times because my father worked in public relations for radio and television. When I was two, we moved to San Francisco. That place shaped my early memory in ways I didn’t understand at the time. We lived on the north side of the bridge, but we’d go into the city to meet my dad—especially into Chinatown for lunch. I think that planted something in me about Asia, a seed that sprouted decades later.

My mother was a teacher, my father was a communicator, and our house was filled with books. We traveled all the time by car—my parents loved road trips. Somewhere along the way I started collecting postcards, keeping diaries, and taking pictures with whatever camera was around. Sometimes it was a Kodak Instamatic and later my father’s Konica or Canon. I was probably six when I started to become the unofficial second photographer in the family.

But the real turning point came years later, in college, when I took a darkroom class. Watching an image appear in the developer… it was magic. If you’ve ever had that moment, you know exactly what I mean. That alchemy is still magical to me today. I became a serious photographer right there.

Majuro, Marshall Islands 1997

HM: You’ve said before that in your early years you dreamt of becoming a professional athlete. When did photography start becoming more serious than sport?

MEH: I wanted to be a baseball player. I was convinced that was going to be my life. Later a golfer. My parents never said, “You can’t do that.” I grew up believing anything was possible. But by college it was obvious I wasn’t going to make a living playing sports, and my interests were shifting anyway to documenting my extensive travels, camera in hand. This included a trip to Siberia. I majored in History for my bachelors and Pictorial/Documentary History, a major I created, for my Masters degree. Freezing moments of time fit in perfectly with this line of study.

I was a bit lost though when I graduated, but then, fortuitously, I got a job with The Merv Griffin Show. I started running the greenroom, taking care of guests and then on my own, I would document them on stage. That morphed into an official part of my job and helped me build a portfolio. From 1983–86, I photographed everyone—Hollywood stars, politicians, artists, musicians. Orson Welles. Charlton Heston. President Carter. You name it.

It was surreal and educational, but not glamorous in the way people imagine. You’re learning how to deal with high-level personalities without being intimidated. That prepared me for a lot of things later.

At the same time, to pay the bills, I was shooting real estate. That taught me discipline like nothing else: 50 5x7 black and whites of every house, printed perfectly. Not glamorous, but a great way to master exposure and process. I loved those late nights in my garage darkroom with my rock “n” roll 8-tracks keeping me company.

HM: What was your first major personal project—the moment you felt your own photographic identity forming?

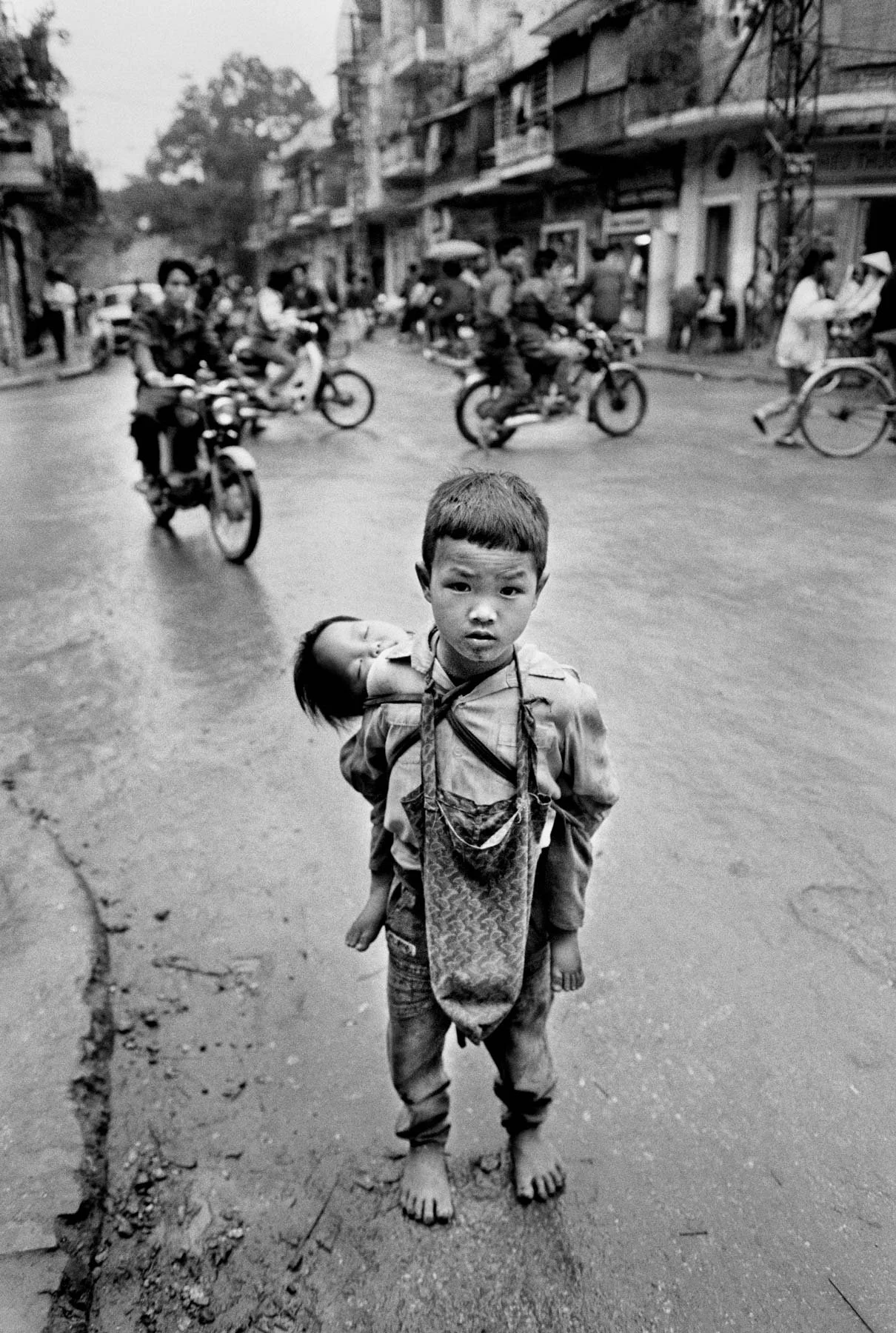

MEH: Vietnam, early 1990s. Like a lot of Americans who grew up in the ’60s and ’70s, I watched the war on television. At one point I actually thought, “Vietnam is beautiful,” not understanding the scale of the violence behind the images. That contradiction lived inside me for years.

When I finally went there in the early ’90s, I was stunned by how different reality was from the mythology. The work I did there ended up being published widely, and for the first time I felt I had created something meaningful—something that had a voice. I still love Vietnam, both the country and its people. I just covered the 50th anniversary of the end of the war.

I’ve always gravitated toward portraiture—environmental portraits, and “eyes are the window to the soul” type portraits. One of my biggest influences was W. Eugene Smith. It’s ironic that my father had painted an interpretation of Smith’s photo of his children walking into the forest. That painting hung in our house throughout my childhood. Years later, after seeing “The Family of Man” I realized the connection: Smith was always with me.

Hanoi, Vietnam 1992

HM: Before we get deeper into Japan and North Korea, what were those early years of traveling in Asia like?

MEH: Chaotic, curious, wide-eyed. I went to Thailand, Cambodia, China—constantly bouncing around. I was learning to see. Learning to travel alone. Learning that photography wasn’t just technique; it was access, connection, and humility.

I didn’t speak the languages yet, but I was always good communicating with people without words. I’m naturally curious. People usually respond to that.

Asia in the early 1990s was very different then it is now. Vietnam and the US were about to establish relations again. China was in that in-between stage—emerging but still rigid. Everywhere you went, you could feel history pressing up against modernity. That tension became one of the themes of my life’s work.

HM: One of your signature projects, The Way of the Japanese Bath, began with a single accidental shoot. What happened?

MEH: In 1992 I went to Beppu—the hot spring capital of Japan—with a girlfriend. I wasn’t planning any kind of project. I just had film with me: Tri-x and some TMAX 3200. In the bathhouses, the steam, the light, the silhouettes… everything was perfect. I shot without thinking too much.

When I got back and developed the negatives, I was stunned. The images were mysterious, sensual, spiritual. They felt ancient and contemporary at the same time. Peterson Photographic published the ones done with the high speed grainy TMAX 3200, and suddenly I had something.

Years later, around 2000, I went back to Japan with the intention of making a book on the hot spring experience. That became The Way of the Japanese Bath. The 4th edition was just released.

Japan continues to affect me deeply—its sense of beauty, order, and impermanence. I learned the language to a conversational level. My ex-wife Mika and still best friend is a tea master, so I entered the culture through the tea room, the kimono, the rituals. That continues to shape the photographer I am.

Beppu, Japan 2000

HM: You’ve mentioned spirituality in Japanese culture—Shinto, Zen, the sense of sanctity. How has that influenced your work?

MEH: Japan has a way of stripping life down to essentials. There’s a lineage of beauty—ceremony, gardens, shrines, light, silence—that goes back centuries. You feel it everywhere: in the way people bow, in the lines of a kimono, in the steam rising from an onsen as the day turns to night.

Shinto, in particular, has always moved me. You walk through torii gates and each gate is like a crossing: from the mundane world into the sacred one. And yet the sacred doesn’t feel separate from life—it's woven into daily existence.

I’m not a religious person in the Western sense, but Japan has helped me understand spirituality as presence.

Photography is presence. Japan made me see that clearly.

Post-Bath Rinse

Arima, Japan circa 2000

Ginzan Onsen, Japan 2018

HM: Let’s talk about North Korea—a subject few photographers have been able to work on so extensively. How did your entry into the country begin?

MEH: My first trip was in 2005, but everything changed in 2008. The New York Philharmonic was invited to perform in Pyongyang. Because it was a cultural diplomacy mission, the North Koreans couldn’t pick and choose who was coming with the Philharmonic. My name was on the list, and they couldn’t say no.

After I returned, I had an exhibition of the work at The Korea Society in New York. The North Korean ambassador to the UN came to see it. He liked the balance of the work—neither propaganda nor a hit piece. He said, “Anytime you want visa, I’ll sign it.” That opened the door much wider.

I ended up going ten times.

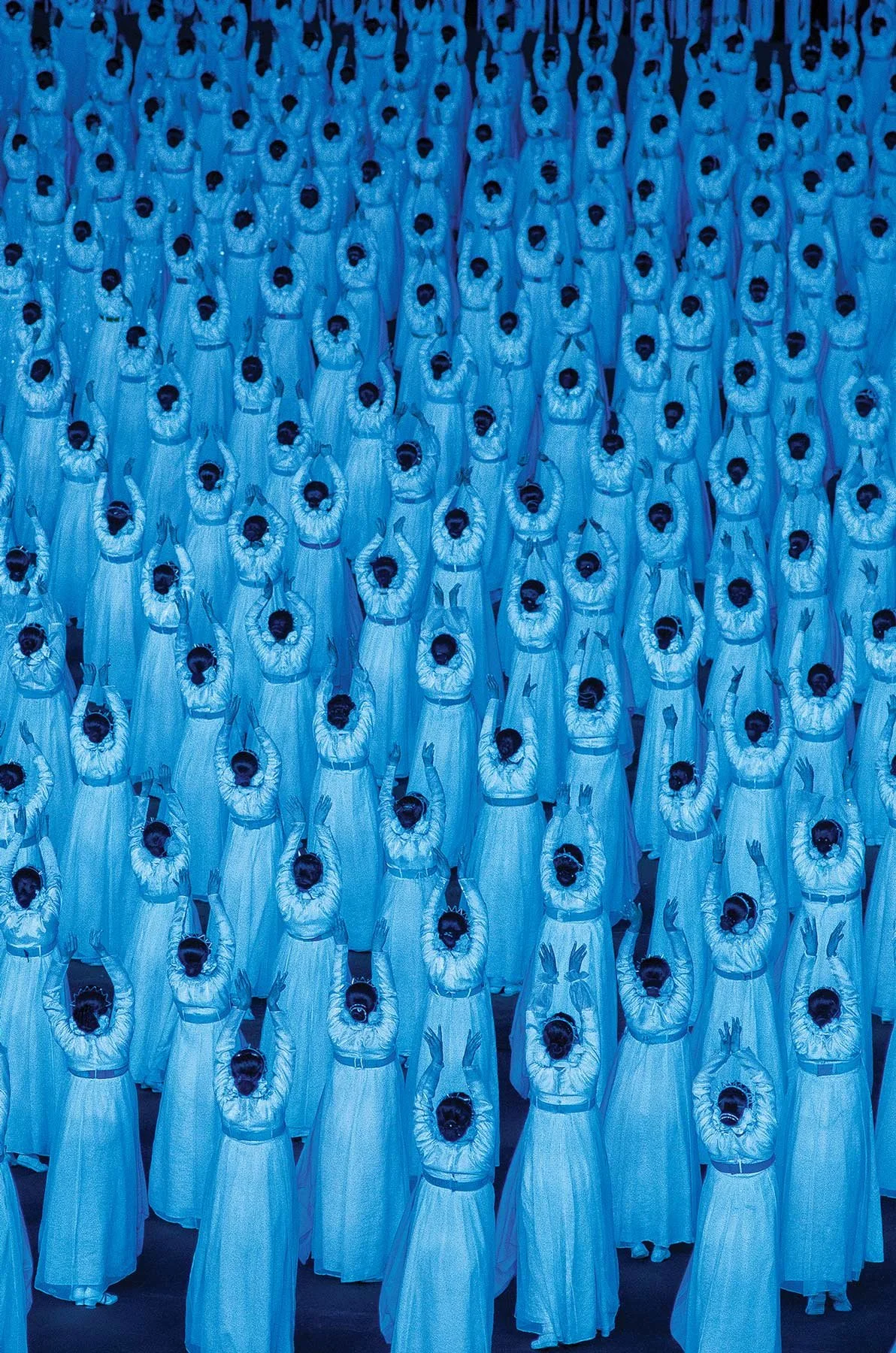

Arirang Mass Games

Pyongyang, DPRK 2010

Statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jung Il

Pyongyang, DPRK 2012

HM: Most people assume that photographers in North Korea only see what the government wants them to see. What was your experience?

MEH: That assumption is both true and not true.

Yes, you go to the monuments and museums. Yes, you have guides. But it would be arrogant to assume that an entire country shuts down its normal life just because foreigners are around.

If you stay open, curious, and respectful—not political—you see things: markets, workers, students, landscapes, daily rhythms. People living their lives.

I studied Korean to get more into the culture. I talked to guides, teachers, children, workers. I heard what they loved, what movies they watched (a lot of them Russian), what sports they followed. We just avoided political subjects.

Every time I went, I was struck by how normal daily life was. It’s the opposite of how the country is portrayed. My goal was not to expose or sensationalize. It was to witness and document.

Traffic Officer

Pyongyang, DPRK 2008

Soldier

Mt. Paektu, DPRK 2011

HM: How did South Korea contrast with that?

MEH: South Korea is incredibly modern, dynamic, fast-moving. North Korea is more like stepping into another era—slower, quieter, more controlled. But the people, the culture, the roots—they belong to the same peninsula. You see the connection.

I photographed both sides extensively. It gave me a sense of the whole Korean story, not just the narratives you hear in the media.

Children on a Farm

Kangwon Province, DPRK 2011

HM: Outside the Koreas, Vietnam and Japan, you’ve spent significant time in Iran and the broader Middle East. What drew you there?

MEH: Iran has long fascinated me. The poetry, the architecture, the contradictions. I studied Farsi for a year before going. When I arrived, I found a culture that is incredibly sophisticated, ancient, and full of complexity. People were warm and well educated.

Iran is a place where history is almost a physical presence—it’s in the tiles, the gardens, the mountains, the stories. That appealed to me as a historian and as a photographer.

The Middle East in general has drawn me because it’s the birthplace of so much—religion, conflict, myth, beauty, tragedy. Photographing there is like photographing the roots of civilization.

HM: Let’s go deeper into your relationship with Japan. After the bathhouses, how did your work there evolve over the years?

MEH: Japan kept opening doors for me, culturally and visually. Once I started the bathhouse project, I realized Japan wasn’t just a place to photograph—it was a place to learn from. I spent years traveling through the country: temples, shrines, small towns, coastal villages, big cities. I photographed everything from onsens to sumo to tea ceremonies.

I learned how to read to some degree the culture’s subtleties. The Japanese way is not loud. It’s not overt. It’s beauty is expressed through restraint. Light through shoji screens. The sound of wind in bamboo. A bowl placed quietly on a tatami mat.

Since Mika is a tea master I entered the culture through the tea room. Through her, I learned about the kimono—the symbolism, the way the obi is tied, the colors for each season. It made me appreciate how much Japan communicates without words.

Japan taught me that photography is as much about what you don’t show as what you do.

Japanese Macaque

Nagano, Japan 2025

HM: The 2011 Tōhoku tsunami became another long-term project for you. How did that begin?

MEH: I arrived in Japan just weeks after the tsunami. I traveled north—Otsuchi, Ishinomaki, Kesennuma—places that had been devastated. Entire towns demolished. Boats on rooftops. Cars in trees. Streets gone. Lives lost. But also an astonishing sense of dignity and order.

I photographed not just the destruction but the response—the resilience, the volunteers, the rebuilding. Over the years I’ve returned again and again. Fifteen years later, I’m still expanding on that body of work. Japan has rebuilt an entire coastline, and there’s a new 600-kilometer memorial trail. I’ve walked parts of it. I want to walk the entire route with a camera.

The tsunami wasn’t just a disaster story. It’s a human story—grief, recovery, memory, and the power of community.

Tsunami Wreckage

Otsuchi, Japan 2011

HM: Let’s return to North Korea. You visited ten times. What surprised you the most?

MEH: They are much more aware of the outside world than I expected.

We all grew up with images of North Korea as this cold, militarized dystopia. And yes, there are strict controls, propaganda, surveillance. But inside that, there are people living real lives—laughing, working, studying, falling in love, singing, raising kids.

I’ve always been struck by how similar people are in the big picture of life. Curiosity, humor, shyness, pride, hospitality. I’ve had meals with guides where they asked all sorts of questions about America. I’ve talked about sports with bus drivers. I’ve walked through deserted parks with teachers who told me about their childhoods.

None of that fits the stereotype. And that’s a good thing.

Kindergarten Performance

Chongjin, DPRK 2011

HM: Your images from North Korea feel intimate, considering the strict environment. How did you achieve that?

MEH: Respect. Empathy. Patience. Curiosity. And no politics.

I never went to North Korea with an empty cup, open to whatever came my way. I never challenged people’s identities or beliefs, nor did they try to challenge mine. They let me in. They showed me their world as much as the system would allow.

I can also read and write Korean and at the time of my travels there spoke intermediate Korean which helped enormously. Even just greeting someone properly in their own language softens the walls. I would suggest to anyone going to a foreign country with a camera in hand or not, learn some basic phrases in the local language.

Pyongyang, DPRK 2008

HM: What have you learned about photographing cultures that outsiders tend to misunderstand?

MEH: Humility is everything. You can’t walk into a place believing your worldview is the correct one. If you do, your photos will suffer.

You must leave space for the unexpected.

If you arrive in North Korea expecting darkness, you’ll miss the light. If you arrive in Iran expecting hostility, you’ll miss the warmth. If you arrive in Japan expecting perfection, you’ll miss the vulnerability.

It’s vital to listen. It’s difficult to learn with your mouth open. I love what Mark Twain said, “It is better to keep your mouth closed and let people think you are a fool, than to open it and remove all doubt.'' That doesn’t mean that I don’t talk a lot, but I am a really good listener.

Kyiv, Ukraine 2022

HM: Your time in Iran stands out. You mentioned studying Farsi before going. What did you discover there?

MEH: Unfortunately I’ve forgotten most of the Farsi I studied. If you don’t use it, you lose it. But it was such a valuable tool to have for my two trips there in 2007. Iran is one of the most culturally rich places I’ve ever been. Poetry is alive there. People can recite Hafez or Rumi from memory. They love conversation. They’re curious about the world. The architecture is breathtaking—tilework, mosques, bazaars, gardens.

I traveled throughout the country—Tehran, Isfahan, Kashan, Yazd, the island of Kish, the Caspian Sea. Everywhere I went, people invited me to sit, drink tea, talk. They wanted to know what Americans think of them. They wanted to tell me about their history.

It reminded me that the world is always more nuanced than the headlines.

HM: You’ve photographed in over 100 countries. How do these experiences shape you?

MEH: Traveling has reinforced what I believe I’ve always known, that every culture has depth, humor, contradiction, tragedy, beauty. People everywhere fundamentally want the same things: to be respected, to be heard, to feel safe, to take care of their families, to find some joy in life.

Travel strips away the illusion of difference.

Kharkiv, Ukraine 2022

HM: You’ve mentioned before that you’ve had a serious ski accident where you lost your memory. How has that experience shaped your worldview?

MEH: My memory of most of that day never came back. Incidents like that are powerful reminders that life in the grand scheme of things is short. I think that’s why I work and photograph the way I do. I never liked the expression “Killing time.” Time is way too valuable to kill. I felt that way before the accident and that experience on the slopes only reinforced it. Never wait for tomorrow because tomorrow may never come. But I also love what I do so the saying, "if you love what you do, you'll never work a day in your life" definitely applies to me. It is not a burden for me to be what some might call, “a workaholic.” That doesn’t mean what I do is one long vacation, I’ve gotten frost bite in blizzards on the North Korea/Chinese border and on the sky slopes covering the Winter Olympics in China and suffered from hypothermia on the Everest trek. I was also brought in for questioning in both North Korea and Iran and wasn’t sure if I was going to walk back out with my freedom. I also pushed my luck almost too far when covering the wildfires in LA in January 2025.

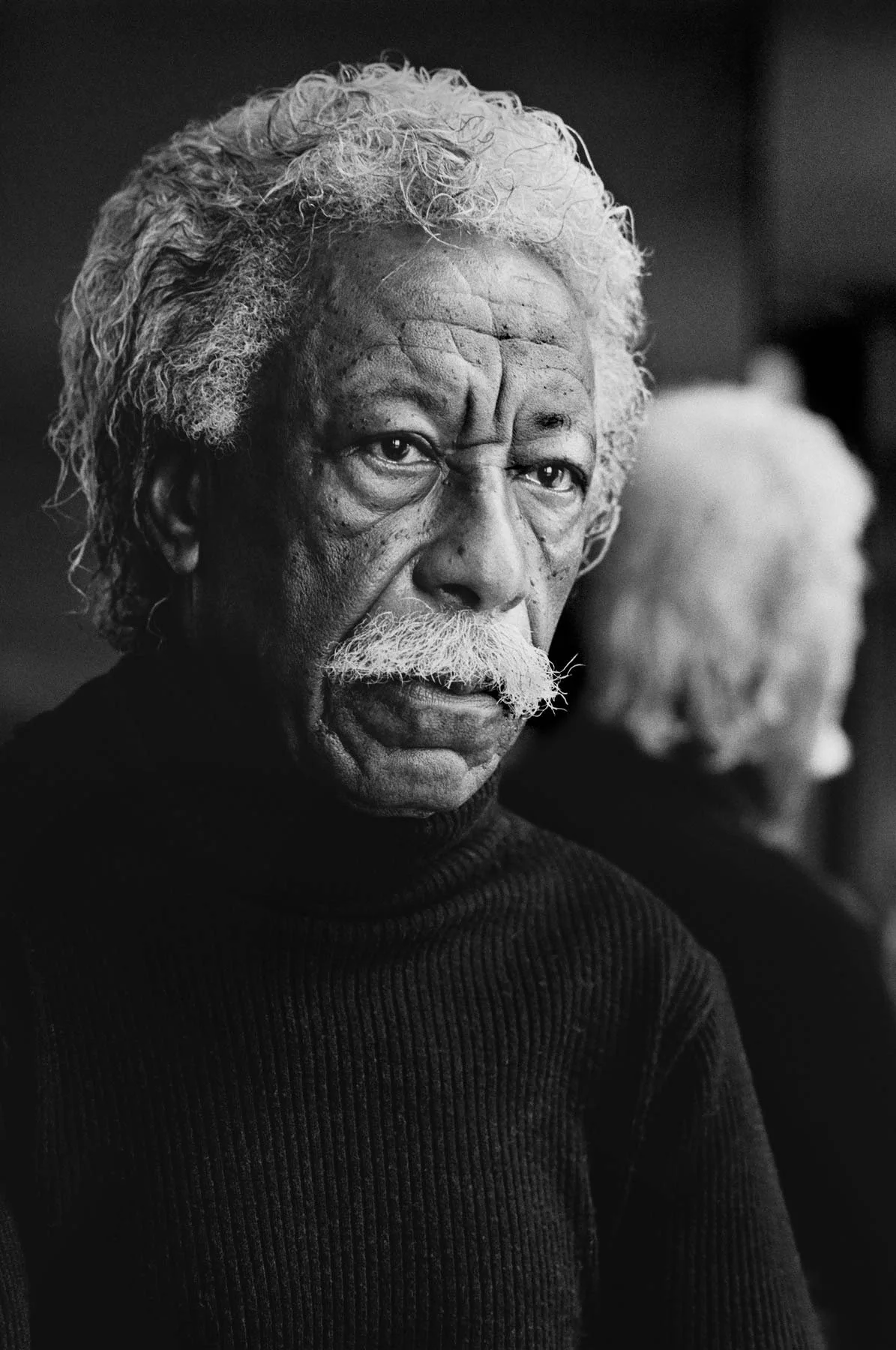

Sebastiao Salgado

Los Angeles, USA 2013

Gordon Parks

New York, USA circa 1995

Alfred Eisenstaedt

New York USA 1993

HM: With all your experience across cultures, what philosophies guide you when you travel and photograph?

MEH: Stay curious. Stay humble. Don’t judge. Not an easy thing to do but I try. Listen more than you speak. Be generous. Be patient. Don’t take yourself too seriously. Be grateful.

And keep your eyes open—not just for images, but for meaning.

A photograph is a moment of empathy. Travel is a lifelong practice of empathy. And empathy is the closest thing we have to understanding one another.

Orphaned Orangutans, Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation

Borneo 2019

HM: You have an unusual range in your photographic career—long-form documentary work, deep cultural projects, and then elite sports photography. How did sports enter your professional life?

MEH: Sports were actually my first dream. As a kid, I thought I would become a professional baseball player. Later a golfer. I grew up playing baseball. My dad was amazing. He would practice with me even though he could only use one arm because of polio and his spine was deformed. He was an incredible role model. I even tried out for the San Francisco Giants. Eventually I had to admit I wasn’t going to make a living at it, but the love for the game never left.

Fast-forward decades later: photography brought me back into sports. I began photographing Major League Baseball—specifically the Dodgers—before and now during the Shohei Ohtani era. Suddenly I was three feet away from one of the greatest players in history, hearing him chat with his teammates, watching the way he grips the bat. It’s surreal, like childhood merging with adulthood. My number one highlight however is when I caught a foul ball with one hand while holding onto my Nikon Z9 with a Z 400mm f/2.8 on a monopod in the other at Oracle Park, the home of the San Francisco Giants.

Sports photography demands a different mentality than documentary work. You have to know the game to anticipate the plays. It’s a dance of instinct and preparation.

Los Angeles Dodger Shohei Ohtani

Los Angeles, USA 2024

HM: You've photographed multiple Olympics. What’s unique about shooting the Olympics compared to other sports events?

MEH: The Olympics are an enormous machine—thousands of athletes, dozens of venues, unbelievable logistics to manage. You have to plan every minute of your day and at the same time be flexible. In Paris, most of the photographers were crowding in to get Simone Biles on the balance beam. I gave up that opportunity to wait for her at the uneven bars so I could get a head on position instead of sprinting over with the pack and jockeying for position. That decision gave me the best image I made that day. Sports photography is doing your homework then giving yourself over to instinct.

Simone Biles

Paris 2024 Summer Olympics, France

Eiffel Tower

Paris 2024 Summer Olympics, France

HM: How do you mentally switch between shooting something like North Korea—full of political and human complexity—and photographing sports with extreme precision?

MEH: Both require total presence.

In sports, you’re present physically—you track movement, light, fractions of seconds. In documentary work, you’re present emotionally—you listen, observe, wait for humanity to surface.

But both forms of photography share one core principle: anticipation.

In sports, you anticipate the moment before it happens. In documentary, you anticipate the emotional truth before it reveals itself.

So although they seem far apart, they strengthen each other. Shooting baseball sharpens my reflexes. Shooting North Korea sharpens my empathy. Together, they keep me balanced.

Relay Race

Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics

HM: Teaching has become a major part of your life. What does teaching photography give you that shooting doesn’t?

MEH: Community. Photography is a solitary pursuit. Workshops bring together people who are open to learning and eager to share. That creates a kind of creative family. I love that.

My mother was a schoolteacher, so maybe some of this is inherited. But I genuinely love watching people improve. When a student suddenly “gets it”—when they start seeing light or gesture or perhaps most importantly, story—that is extremely satisfying.

I’m not an easy teacher. Students pay real money, travel far, use their vacation days. I take that seriously. I push them. I don’t let them shoot mindlessly. I teach them to direct, observe, ask questions, look at hands, pay attention to lines, understand why they’re photographing what they’re photographing. At its best, photography isn’t button-pressing. It’s making art or recording history or a combination of the two. I take that seriously.

HM: What are the most important things you teach about visual storytelling?

MEH: That a story has structure.

A human focused photo essay tends to need:

1. An establishing shot

2. An environmental portrait

3. An intimate portrait

4. Detail shots

5. Transitional images

6. A closing image

Once you understand that grammar, you can tell any story—from a village in Vietnam to a baseball game in Los Angeles.

I also teach the importance of connection. If you want a great portrait, you must connect with your subject. That might take five minutes or five days. But without connection, you have very little or perhaps nothing at all. Most people, including myself are shy, but standing far away with a long lens and trying to sneak a shot seldom creates a powerful result. As the late great Robert Capa said, "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough."

ICE Protest

Los Angeles, USA 2025

ICE Protest

Los Angeles, USA 2025

HM: Many of your workshop students have successful careers outside photography. What do you tell people who aren’t sure whether they’re “real photographers”?

MEH: Everyone is a real photographer if they commit to seeing.

Most of my students are lawyers, doctors, engineers, entrepreneurs—people with demanding lives. Photography is their avocation, not their occupation. And that’s fantastic. An avocation enriches your life. It adds depth and joy.

Photography doesn’t belong to professionals. It belongs to anyone who wants to express something with a camera.

Azy, International Orangutan Center

Indianapolis, USA 2018

Chomel and her son Putra

Singapore Zoo, Singapore 2018

HM: Technology—smartphones, AI, computational imaging—is changing photography quickly. How do you see the future?

MEH: Tools change, our creative impulse won’t.

Smartphones have made everyone a photographer in a very real sense. That’s not a threat—it’s a reality. But what you do with the image recording device in your hand is key. You can take a lot of mindless photos and never experience what is in front of you or you can use it as a tool to be in the moment and dig deeper into whatever is in front of your lens. Way too often however, smartphones are being used for self-aggrandizing “I was here” photos.

AI will change everything, especially commercial photography. But it won’t replace human insight, lived experience, empathy, or the ability to connect with another person through a lens.

A camera—whatever form it takes—is just a tool. The question remains: Why are you taking the picture? What do you want to say?

Palisades Fire

Los Angeles, USA 2025

Palisades Fire

Los Angeles, USA 2025

HM: After all your travels, experiences and creative pursuits—what ties it all together? What’s the through-line of your life’s work?

MEH: Curiosity. Humanity. Empathy. Optimism. The belief that the world is far more beautiful than it is dark. That can be challenging after some of my experiences covering wars, riots, fires and earthquakes. But even in those situations you can find the best of humanity.

I’ve learned to walk into a place with an empty cup. To let the world fill it. To trust that people everywhere want similar things: dignity, family, safety, connection. Every barrel has its bad apple but we can’t let that overshadow the majority.

Every place I’ve photographed has taught me something about our shared humanity.

Photography is my way of honoring that universality.

All images © Mark Edward Harris unless stated otherwise